Time to Remember

Truth Hounds is a non-profit organization that has been investigating and documenting war crimes and crimes against humanity since 2014. Since the Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Truth Hounds team has completed about 20 field missions, during which they have interviewed dozens of witnesses and victims of war crimes from 11 regions of Ukraine. In total, since 2014, Truth Hounds have collected over 2,000 testimonies in Ukraine. The team has also experience working in Belarus, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan and Kazakhstan.

“An hour later, someone opened the door, and a Russian soldier said: ‘Pull the hat over your eyes, and face the wall, we were ordered to shoot you.’” This is a quote from the testimony of 48-year-old Victor Apostol, a resident of the village of Vysokopillia in the Kherson region, where he was born and lived his entire life. In 2011, Victor completed his service at the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and for the past three years he had been working as a security guard at a grain processing plant. On April 23, 2022, he, his wife and their 10-year-old son managed to evacuate to Kryvyi Rih—after a 42-day occupation. In early June, the Truth Hounds team spoke personally with Victor.

Occupation

Hostilities near the village of Vysokopillia began on March 9, and on the 12th, the village was occupied by Russian troops. That day, Victor recalls that while entering the village, the Russians fired at the local hospital, damaging the entrance to the building. However, as Victor says, no Ukrainian military men were stationed at the hospital on the day of the shelling or the day before. On September 4, almost half a year after the start of the Russian occupation, servicemen of the Ukrainian Armed Forces hung the Ukrainian flag on the roof of the hospital, marking the liberation of Vysokopillia.

The Truth Hounds team knows that the occupying forces in Vysokopillia included not only representatives of the Russian Armed Forces, but also their proxies from the “DPR.” They differed in their knowledge of Ukrainian, their inferior military uniforms and equipment.

“We distinguished between the “DPR” residents and Russians on the basis of their accent and language. The Russians did not understand us, they demanded that we speak in Russian,” Victor explains.

After entering Vysokopillia, the occupiers immediately set up checkpoints and occupied houses on the outskirts of the village. They equipped a mortar position on the grounds of the hospital, placing several IFVs there. The Russians and their accomplices from the “DPR” regularly got drunk and terrorized the local population: they robbed shops and pharmacies, stole cars and other property from the residents. Victor says that his Lifan was also seized.

From the first days of the occupation, local residents started disappearing. Victor heard many stories about the behavior of the occupying forces towards the local population.

“Drunken soldiers knocked on the door of the house where Inna lived. She opened it to ask what they wanted. They started molesting her. Her children, boys aged 7 and 10, were behind the door at that time and asked their mother what was going on. Then one of the soldiers fired at the door. One boy was apparently injured [. . .] As a result, he was taken to Velyka Oleksandrivka, because our hospital was no longer open. I don’t know what happened after that. I heard this story even before being taken captive,” Victor says.

Captivity

On April 13, around 3:00 p.m., Victor was at home with his wife and son. From his balcony, he saw that a Ford stolen from a local resident and marked with the letter Z was heading for his building. The car stopped at the entrance, and immediately after shots were heard and a woman started screaming. One of the Russians ordered the locals to leave the basement of the building, threatening to throw in a grenade if they disobeyed.

A few minutes later, there was a knock on the door of the Apostols’ apartment. When he opened it, he saw his friend, who told him that he was in trouble and needed to come down immediately.

Descending into the basement, Victor saw two Russian soldiers: one of them—a man who was around 25 with a distinct Russian accent—was sitting on a chair, holding a gun on his lap, the other one, an even younger guy who looked Asian, whom Victor calls “Buryat”, was searching the basement where residents had their own separate rooms.

In Victor’s room, the Russians found walkie-talkies. On February 25, his wife’s brother, who moved to Vysokopillia immediately after the start of the full-scale invasion, brought them from Kherson.

“He gave me a walkie-talkie in case we lost contact, so that we could talk to each other. We both had two walkie-talkies. I kept them in the basement just in case but didn’t use them”, Victor says.

The Russian military ordered all the women to get into the entrance. The men were lined up outside the building. “Buryat” pulled back the bolt on his gun and pointed the weapon at them, shouting: “Choose who’s going to be snuffed out first.” At that exact moment, mortar shelling began from the neighboring village of Kniazivka. Victor could hear the walkie-talkie of one of the soldiers: “They are shelling the headquarters,” after which the Russians got into the car and drove away. 20-30 minutes later, the shelling ended and the Russians returned. Seeing how the same Ford was approaching the building, Victor realized: they are coming for him.

“I kissed my wife and son, and told them that I was going outside so that they [Russian military—Author] wouldn’t bother the family anymore.

When Victor exited the building, the familiar faces were already waiting for him—four soldiers were standing by the car. “Buryat” came up to Victor and punched him in the face, shouting: “Why didn’t you tell us that you are a cop?” Victor replied that he’d retired 11 years ago.

Then the Russian military decided to search Victor’s flat: they rummaged through everything, including the child’s toys, with a bayonet knife, and took his wife’s laptop—allegedly to find evidence that Victor was a spotter. Then they pulled a woolen hat over his eyes and put him in the back seat of the car. Through the hat Victor could see that he was being taken to a building on Pushkin Street.

They took him to a small room and locked him in there, propping up the door with some kind of object.

“I’ll tie something here, if you move, it will explode,” one of the Russians said when leaving.

Torture

The occupiers came back an hour later.

“Pull the hat over your eyes, and face the wall, we were ordered to shoot you,” the captive recognized “Buryat’s” voice. He ordered him to go outside and strip down to his underwear to check his tattoos. “Buryat” then started asking Victor about local ATO veterans, hunters and volunteers.

“I don’t know,” Victor answered.

“Cut the crap, you are a cop, you know a lot, but you don’t say much,” “Buryat” shouted, as he poured a bucket of cold water on Victor.

He was allowed to get dressed only 20 minutes later. “Buryat” repeated the question, threatening to go and get Victor’s wife and son. Victor gave the names of several hunters who by that time had already left the occupied territory. However, this answer did not satisfy the Russians—they took him back to the room, put him on a stool and tied him to it with electric wire, tied up Victor’s hands and “gave him time to recall” a few more names until morning.

The next day, Victor heard the familiar voice again, ordering him to pull the hat over his eyes and face the wall.

“So, did you recall?” asked “Buryat”.

Victor replied that yesterday he had told everything he knew. Hearing the sound of the gun bolt being pulled back, he began to think that his life was over.

“After the first shot, I felt a pain in my left shoulder blade, and fell to my knees,” Victor says. “He fired again. Four more shots in the back and one in the arm. Then he reloaded the gun, fired several more shots over my head and said: “Don’t shit yourself, it’s a traumatic pistol.” I heard the gun bolt click again and another shot was fired. After which I felt a sharp pain in the back of my left leg. “Buryat” said: “That one is so that you don’t run away.”

After the shooting, the Russian military did not provide Victor with any medical aid.

“It’s okay, he’ll live,” “Buryat” said.

Victor lay on the cold floor bleeding heavily until morning. It later turned out that the “control shot” had been fired from a firearm. Fortunately, the bullet went clean through and did not hit the bone.

On April 15, the doors opened again, but the typical command was not given. Two people came inside: “Buryat” and a Russian military man unknown to Victor. He put the gun to Victor’s wounded limb and asked if he recalled anything. Victor replied that he had already told everything he knew.

“Since you can’t recall anything, we have nothing to talk about,” the Russian answered, who then ordered “Buryat” to deal with it himself. Later Victor realized that this serviceman was most likely the Russian commandant of Vysokopillia nicknamed “Bronia.”

After that, Victor was dragged out by his arms into the yard. His wounded leg was so swollen that he was unable to walk.

“Since you don’t want to cooperate with us, then we have no need for you,” “Buryat” said, after which he fired a round over Victor’s head, threatening: “If you do not recall the information by tomorrow, then this time you will be wasted for real.”

The next day, the Russians brought another civilian into the room, a local resident named Maxim. He had also been shot in the left leg, and the wound was fresh and bleeding. Victor heard one of the soldiers offering Maxim to choose where they should shoot him next: in his foot or his knee.

On the morning of April 17, someone entered the room again where both men were being held, and as always ordered Victor to face the wall and pull the hat over his eyes. He had never heard the voice of this military man before. He allowed him to remove the hat from his eyes and started asking how Victor got here. Victor told about his walkie-talkies and how he used to work as a policeman. During the conversation, Victor realized that the military man used to work in the police. Later he found out that his nickname was “Sedmoi.”

“Sedmoi” called a military medic for Victor, who washed and bandaged the wound, complaining that he could not do anything else in these filthy conditions. According to Victor, the medic only examined Maxim’s wound. “Sedmoi” offered Victor a cigarette, promising more comfortable conditions.

The summer shower room

The summer shower room, where Victor was first held on his own, and later together with Maxim, was approximately 1×1.5 meters in size, with a ceiling height of 2-2.5 meters, tiled brick walls and a concrete floor. The furniture comprised a wall shelf and a stool with a plastic seat and iron legs. There was no lighting. During the day, sunlight barely entered through a small window.

“I was guided by the daylight that penetrated through the door cracks and a small window made of thick glass, but I couldn’t see anything through it,” Victor says.

Of course, the summer shower room had no heating.

You could sleep either in a sitting position or on the floor. No one took them to a bathroom. They were not given food or drinking water.

However, on the first night, one of the occupiers tried to help Victor—a 50-year-old military man approached the shower room door and asked Victor if he needed any help. Victor asked for a cup of tea. The soldier brought him a hot drink, but apparently did it without permission, as he asked Victor to drink it down quickly so that nobody would notice. That night he also expressed skepticism about the war.

“Why the hell do I need it, I’d better be working in my mine, why the fuck do I need this war?”

Victor thought that this man had been mobilized in the Donetsk or Luhansk regions. At the end of their first encounter, Victor asked the soldier if he knew when he would be killed. The man did not know. But he added that maybe everything would be fine. This “miner,” as Victor calls him, came on two more occasions. He offered food and water, but refused to provide medical help. During their last encounter on the night of April 17, the “miner” agreed to untie Victor—perhaps because he already knew him a little—and brought the captives a bucket so that they could relieve themselves.

Help from “Sedmoi”

On the morning of April 18, several soldiers opened the summer shower room door, and gave the usual command to face the wall. Victor and Maxim were blindfolded, taken outside and put in the back seat of a car parked nearby. In a short while, they were taken to a nearby building—a private garage in the yard of the house owned by one of Victor’s fellow villagers.

There were two more prisoners inside—a resident of the village of Novovoskresenske with two gunshot wounds and a local man in his 40s. The soldiers, who called themselves “DPRians,” had brought several mattresses and pillows. It was warmer in the garage, the prisoners were not tortured, and they were even given food twice a day, in the afternoon and evening, Victor says. The military had deployed a field kitchen next to the garage. Due to the close proximity of the kitchen, the prisoners could constantly hear the conversations of the soldiers during mealtime. One day—Victor cannot remember which one—one of the soldiers suggested that they shell the center of Vysokopillia.

“Let’s go and shell the two-story buildings, they fucking have some nerve there!”

About five minutes later, Victor heard fire from the gas station near the village and explosions near Haharina Street.

In the corner of the garage, there was a bucket that the prisoners used as a toilet. Someone from the military would empty it out every morning. On occasions, “Sedmoi” would visit the garage and bring with him the same doctor who was checking the wounded.

On the morning of April 19, the prisoners heard: “New prisoners,” and two more civilians—local brothers aged 40 and 42—were brought into the garage. They said that they were detained because they were registered in Kryvyi Rih. Later that day, the military brought in two more civilians: a resident of Pryhiria, who had a new standard Ukrainian passport with no registration, and a man from Zarichne, who did not have any documents at all.

The morning of April 21 brought good news. “Sedmoi” entered the room, announcing that he was releasing the prisoners in connection with the death of the Russian commandant of Vysokopillia.

“Guys, you are in luck, you have been pardoned. “Bronia” has been killed.

After hearing this, Victor realized that the prisoners were being tortured with the commandant’s knowledge.

However, the “pardon” did not apply to everyone—“Sedmoi” told Maxim and the man from Novovoskresenske that they would remain in captivity for some time. He advised Victor to take his passport from the administration building, and refer to him in case of any inspections by the Russian military.

Evacuation

This is how Victor returned to his family. His relatives did not know where he was or if he was alive. On the way home, Victor heard from his fellow villagers that at noon there was a green corridor planned for the departure of civilians to the territory controlled by the government of Ukraine. Together with his wife and son, they went to the meeting place, but instead of the promised buses, they saw only Russian soldiers in Ladas, ordering people to disperse and threatening them with mortar shelling. One of the Russians tried to persuade the residents of Vysokopillia to evacuate to Kherson and Crimea instead of Kryvyi Rih. After waiting for the evacuation until the evening, the villagers went home. That day, Victor’s wife went to the administration to get her husband’s passport, but the Russians could not find it.

The next morning, on April 22, the Apostol family heard that a group of fellow villagers had left the village in cars with trailers. Later, some of them returned, reporting that the rest had managed to escape. The Russians let some through, whilst others had to go to occupied Arkhanhelske, leave their cars there and cross the Inhulets River swimming. Some people lied to the Russians at checkpoints, promising to go to Kherson, but then turned towards Kryvyi Rih near the village of Davydiv Brid.

On April 23, Victor’s leg got much worse, but the couple decided to take a risk—they took the child, two bicycles, a few belongings and set off for Zelenodolsk in the Dnipropetrovsk region. The man recalls that he pedaled with his one intact leg, while his wife carried their belongings and child.

At a checkpoint near Potiomkine village, the Apostol family was stopped by a Russian soldier. He refused to let the couple through, arguing that the Armed Forces of Ukraine would not let Victor in without a passport, adding that he feared for his own safety.

“He said that one of their own soldiers was shot in the leg because he was letting people through,” Victor explains.

However, after Victor referred to “Sedmoi”, the soldier agreed to let the couple go, provided that Victor would go back to the checkpoint to pick up his passport, which “Sedmoi” would bring there. Victor ironically recalls that he promised to do just that. Ending the conversation, the soldier advised the Apostols to ride on the right side of the road, as the left side was littered with anti-tank mines. On the same day, the family managed to get to Kryvyi Rih, and the next day Victor was finally provided with full medical care.

After the occupation

Fortunately, captivity and the injury did not seriously affect Victor’s physical or mental health. Like the majority of Vysokopillia residents who decided to leave the occupied territory, the Apostol family stayed in Kryvyi Rih. They lived with relatives for several months, and later managed to rent a separate apartment. Victor found a job, and his son goes to a local school.

The news about the liberation of his native village, Victor admits, was a real “red-letter day” for him. Especially because of the fact that for the first time in a long while he was able to contact his parents and find out if they were alive and well. However, the Apostol family is currently not going to go back to Vysokopillia—the village is still close to the frontline and needs to be demined, and they are worried about the safety of their 10-year-old son.

According to Truth Hounds, Victor’s story amounts to a war crime: torture and inhumane treatment. International criminal and humanitarian law prohibits torture and inhumane treatment of both civilians and military personnel. The documented story of Victor Apostol has been handed over to Ukrainian law enforcement agencies, who will now work to identify the perpetrators of the crime and prove in court that a war crime was committed. However, the identification of “Bronia” will have only a symbolic meaning, since he escaped justice. A pyrrhic victory for him, though.

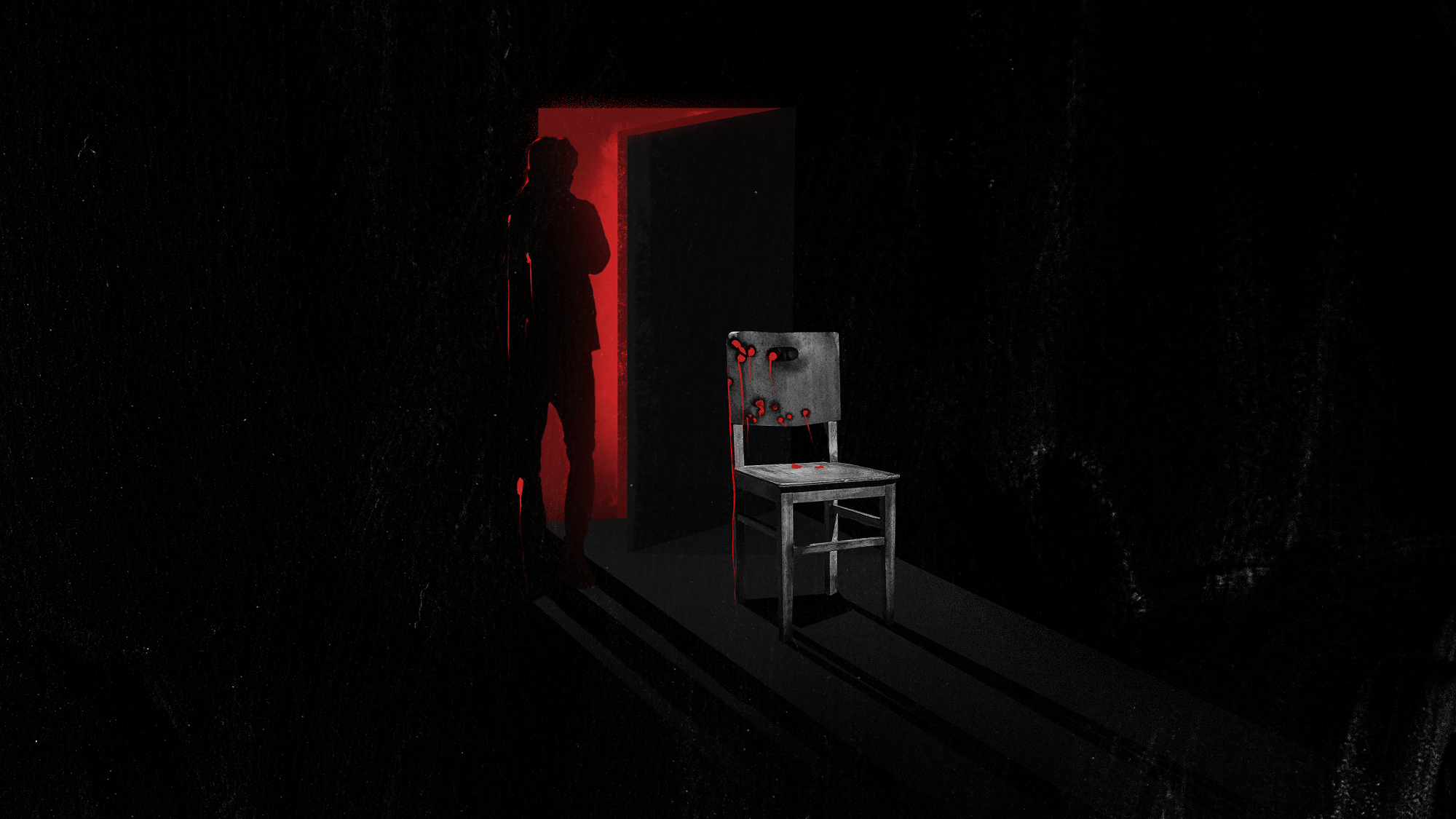

Collage: Vadym Blonskyi

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More