The Rights under the Insoles

1.

A dozen fragments of bricks and stones flew into the windows of the apartment of Mykola and Rayisa Rudenko near Kyiv. Frightened by the sudden tinkle of broken glass, Rayisa jumped out of bed.

At the time, Mykola was in Moscow. Two hours ago, at a press conference for foreign correspondents, if a meeting in a regular apartment can be called so, he announced the creation of a Ukrainian human rights group.

They rode out the storm with few losses. One stone wounded an elderly member of the group, Oksana Meshko, in the shoulder. She was spending the night at Rayisa’s place. Six hefty policemen did not enter the apartment, did not rummage through everything and did not take anyone to the police station as, the women knew, used to happen to others.

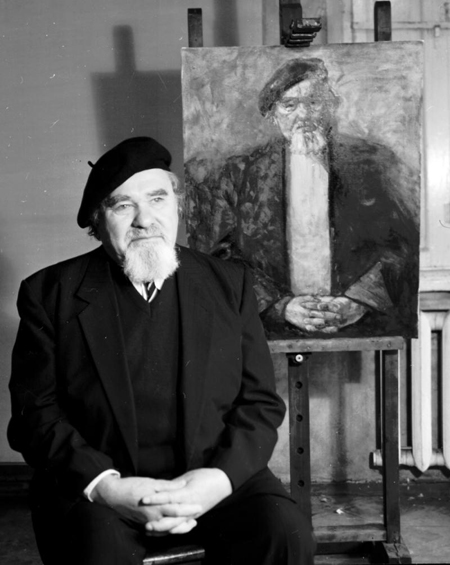

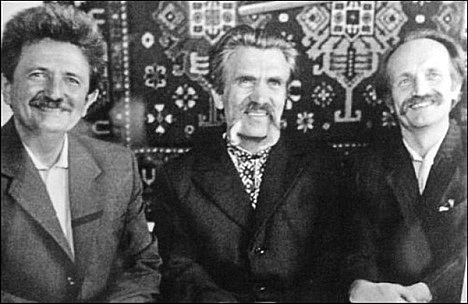

Mykola Rudenko in the middle. Next to him is his wife Rayisa Rudenko. She was the unofficial secretary of the UHG. Photo: Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine, published by the Electronic Archive of the Liberation Movement

2.

Only the stones on the occasion of the first Ukrainian human rights movement.

Mykola Rudenko, a writer whom the Soviet authorities stopped helping with publication, was the initiator. In the late 1960s, he had grown weary of Soviet life. As he wrote, he felt that communism would end in poverty. Then he took a journey by the “decadent West” on the cruise ship called Victory. And later made acquaintance with former GULAG prisoners who returned to their homes after serving ten or fifteen years. This Mykola was no longer fun to his second wife.

But his third wife, Rayisa, accepted Mykola as he was. Without a party card, the Writers’ Union, a Volga with a driver and a four-room apartment in the capital.

A good stenographer, Rayisa retyped Mykola’s manuscripts at night. Later she typed the documents of the human rights group headed by her husband. These documents were of a bigger interest only for the KGB.

3.

In the summer of 1975, the Soviet Union signed the Helsinki Accords with Europe. The document aimed to protect the world from a new redistribution of borders. By flirting with the West, among other things, the USSR undertook to protect human rights and freedoms.

In the spring of 1976, the Moscow “renegades”—as the KGB called dissidents in secret reports—suddenly became active. They set up a group to promote the implementation of the Helsinki Accords to record human rights violations in the USSR. There were plenty of opportunities—concentration camps were full of political prisoners.

Mykola Rudenko had already dealt with these Muscovites. He was arrested for this, but pardoned because he was a veteran and had a disability. The arrest was a warning. But train tickets for veterans with disabilities were half price. So he kept visiting the Muscovites.

Upon learning about the Moscow group, Rudenko thought about a Ukrainian group, which was also supposed to record human rights violations in Ukraine, and in three or four years raise the issue of Ukraine’s independence in a referendum. For Ukrainian dissidents, in contrast to Moscow, the issue of independence was also of great importance. People who joined the group had often served time in prison for promoting the Ukrainian language, for handing out brochures about independence, or for membership in Ukrainian-centric organizations. Their parents were deprived of the right to their Ukrainianness, so the issues of human rights and independence were inseparable for them.

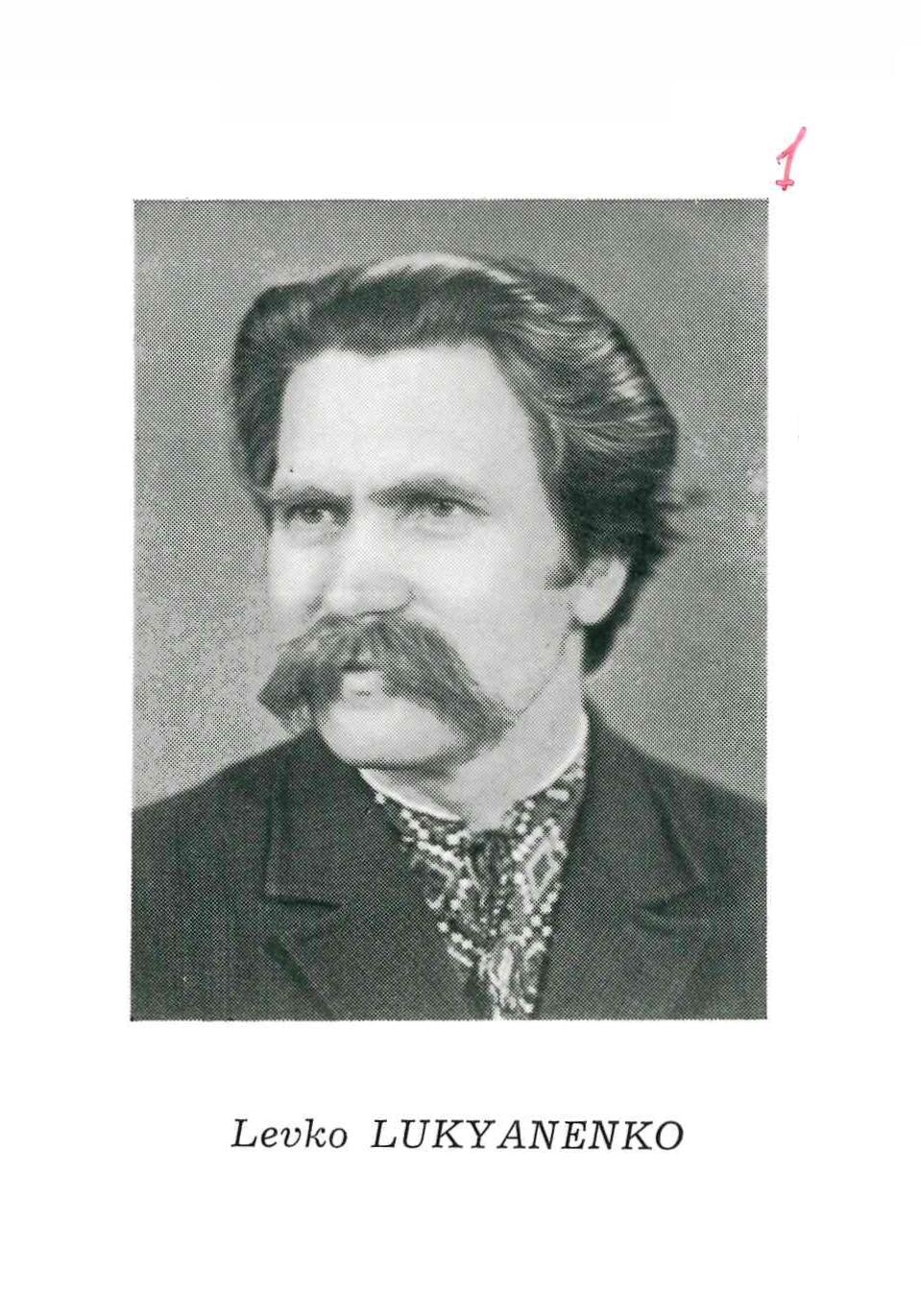

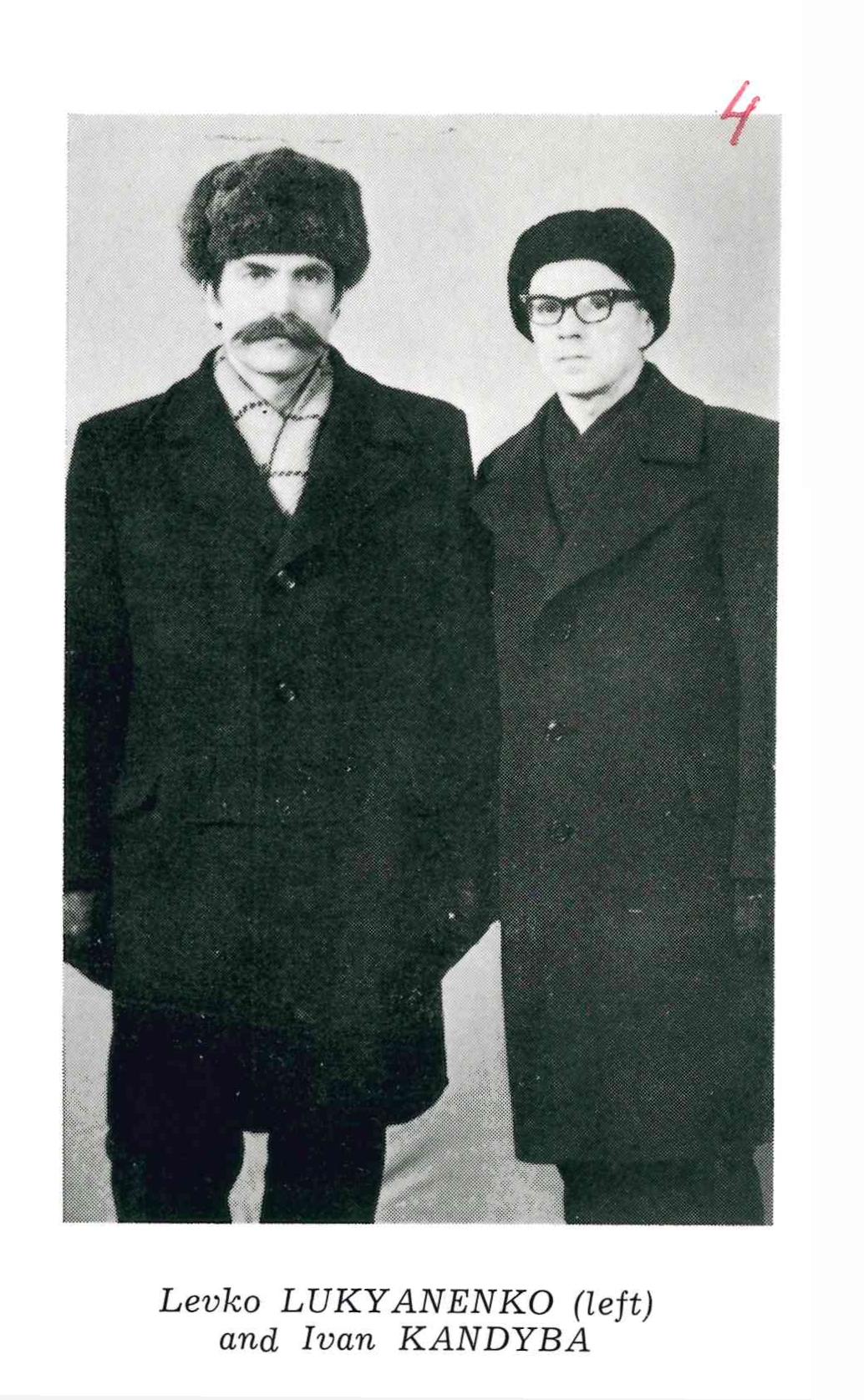

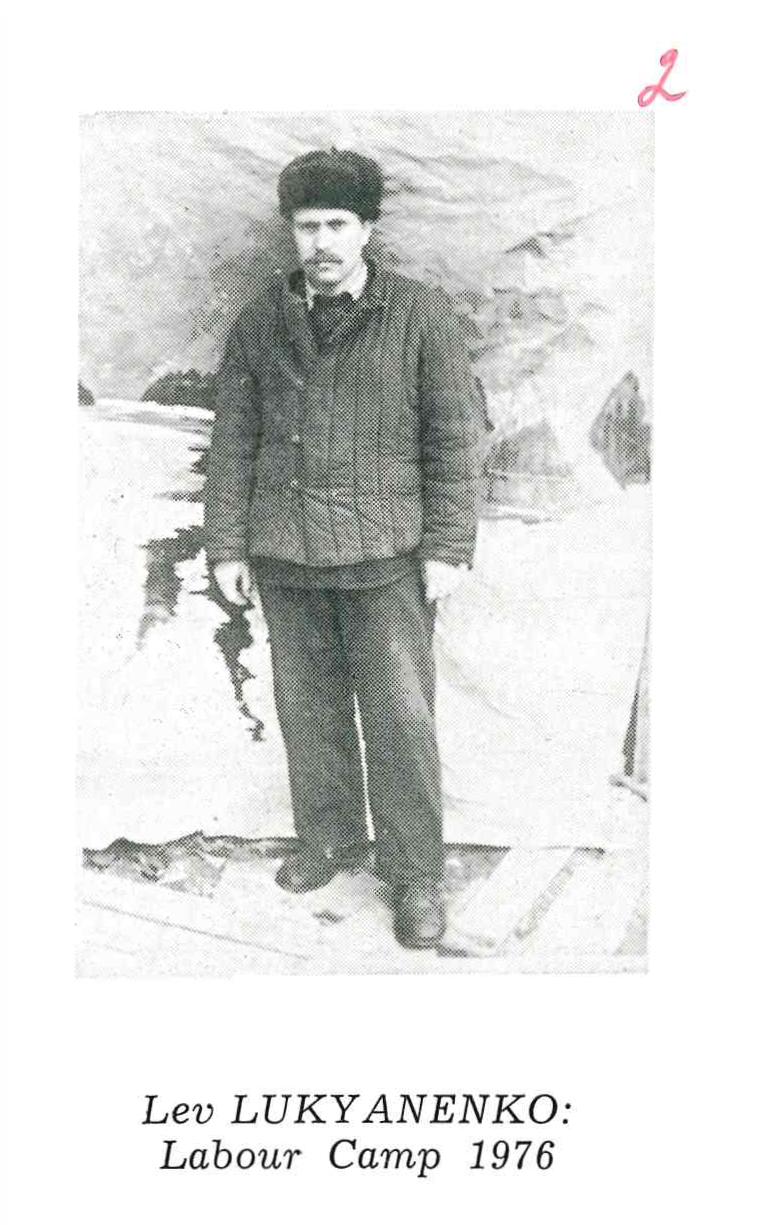

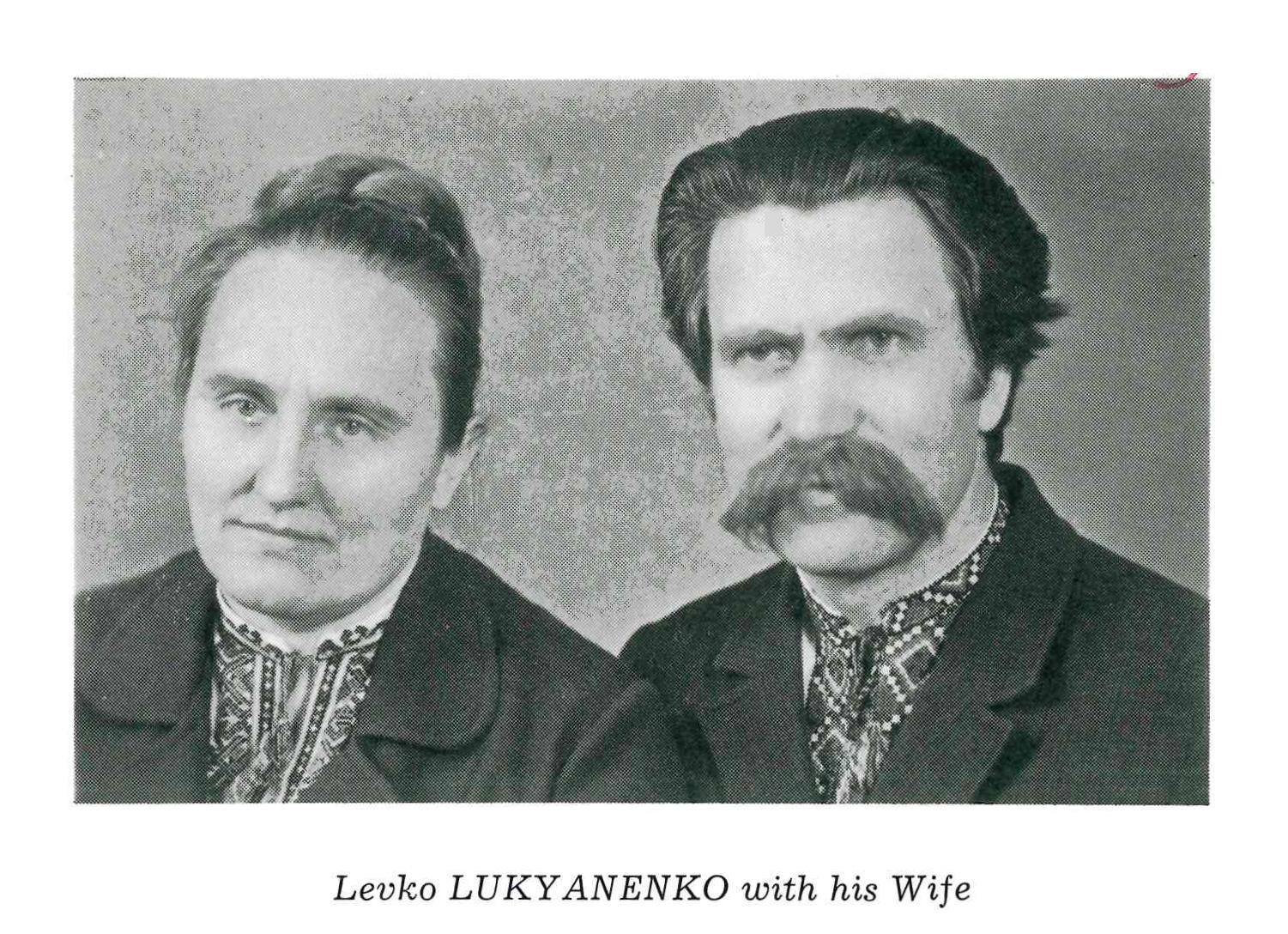

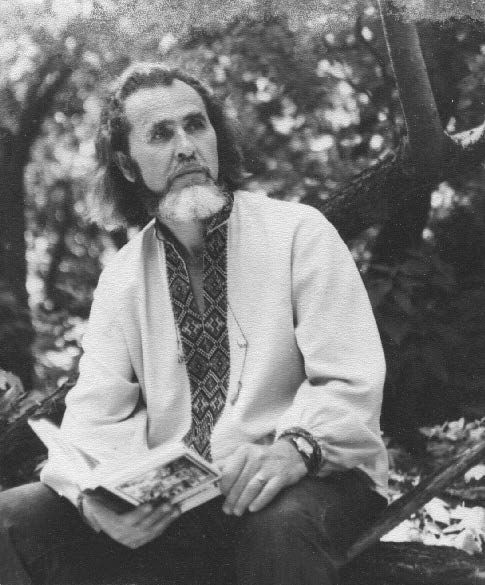

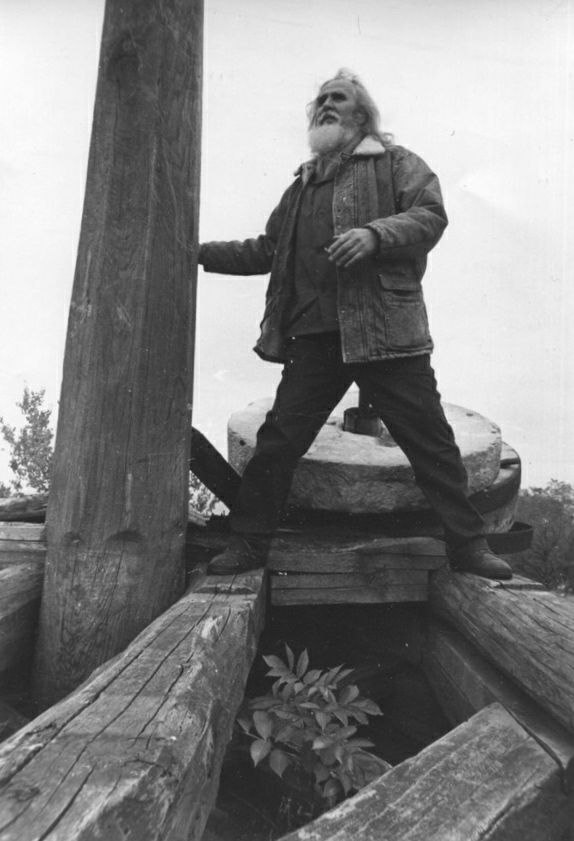

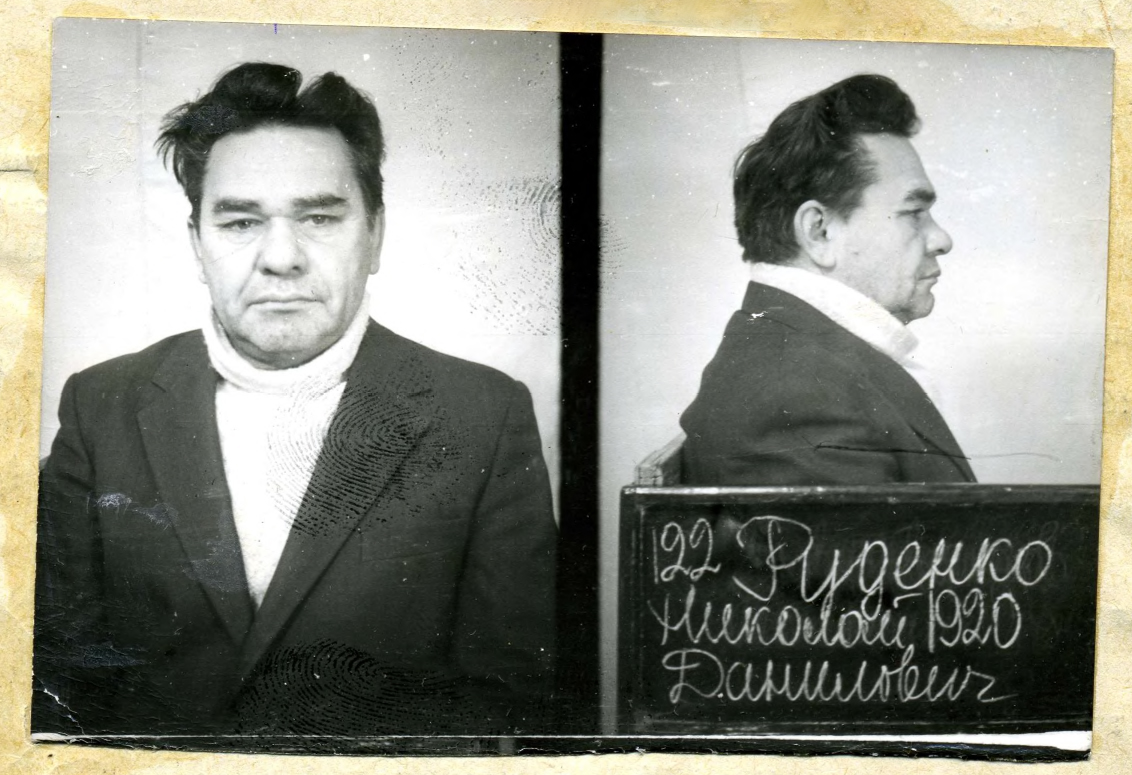

Lukianenko at various ages, in particular, during his first imprisonment at a camp in the Mordovian ASSR, and with his first wife. Photo: OUN Archive in London

4.

There were ten founders: writers Mykola Rudenko and Oles Berdnyk, lawyers Ivan Kandyba and Levko Lukianenko, historian Mykola Matusevych, engineer Myroslav Marynovych, biologist Oksana Meshko and microbiologist Nadiia Strokata, teacher Oleksa Tykhyi and retired general Petro Hryhorenko. There were others whose names did not appear in the documents, but who worked in the group. The son of one of the investigators in the cases of these people recalled a Soviet joke, saying that dissidents—those “sitting apart”—fall into three categories: those sitting in jail, those who have already sat in jail, and those who will soon be sitting there again. Some belonged to all three.

Rudenko looked for the first members among acquaintances and by touch.

He arrived on the doorstep of Lukianenko’s apartment together with Oles Berdnyk. The night before, after escaping surveillance, on one of Kiev’s steep slopes they pondered: Lukianenko, who has just served fifteen years for a booklet on the possibility of Ukrainian independence, has the right not to join, but they do not have the right not to offer.

Nadiia Nykonivna, Lukianenko’s wife, warmly welcomed the strangers, but was frightened. Fifteen years ago, she had not yet even finished printing her husband’s party program when he was arrested and sentenced to death, which fortunately was commuted to fifteen years in prison.

Wandering around the Chernihiv outskirts, Lukianenko slowed down to fall behind his new acquaintances, and pondered. Rudenko believed that the authorities would do nothing because of the “accords.” But Lukianenko knew—everyone would be jailed.

Lukianenko agreed. His wife accepted this, but that day he finally broke her heart. The following year, the last one Lukianenko spent as a free man, she helped him, but would never recover. She did not leave him during twenty-seven years in prison, but said goodbye after his return, a few years before the proclamation of Independence. Nadiia confessed that she wanted human rights, but also some “human love and family.”

Mykhailo Horyn, a teacher from a family of Ukrainian underground members with whom he also had a personal connection, refused to publicly join the group. A few years ago he returned from the camps, and now he could find a job only in a boiler room. Horyn helped the families of the prisoners, but was careful. He said: he would work with group documents, but would not sign anything.

In temper, Rudenko called him a coward. In response, Horyn offered Mykola a stint in prison himself. Rudenko made an example of the Moscow group—they started earlier and have not yet been sentenced.

But Horyn knew well: “When fingers are cut off in Moscow, heads are severed in Ukraine.” Afterall, Mykhailo said, there would be someone left to join the ranks when the current members of the group were imprisoned.

5.

Oksana Meshko was the oldest member—she was over seventy. She had grey hair, was thin, had a tenacious look and a pictorial profile. Even in an old coat and shoes she carried herself with dignity. Her parents were repressed in the 1930s, and she had already served time in the camps. Despite her age, she was perhaps the most decisive: she went everywhere, held negotiations, issued newsletters, and brought everyone together in difficult times.

The KGB, taking into account her age, decided not to send Meshko back to the camps, but ordered compulsory treatment.

Oles Berdnyk, a science fiction writer, was almost two meters tall. With long grey hair, he resembled a wood spirit or a hippie. He was already familiar with Russian concentration camps, and was released through “repentance,” but apparently never repented.

KGB psychiatrists remotely “studied” the writer’s psyche and found signs of schizophrenia. Because “in some of his works he sounded delusional.” They said that under the guise of science fiction Berdnyk tried to promote nationalism. His cosmonauts ascended Mount Hoverla (the highest mountain in Ukraine—R.) before the flight—so they were “space Ukranian nationalists.” Secret reports by KGB officers state that he was also to be forcibly treated. Although later they changed their mind. Another “repentance” freed Berdnyk from imprisonment.

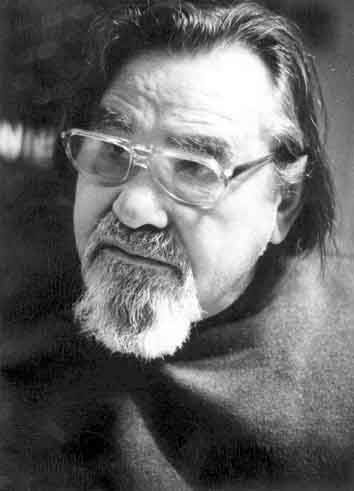

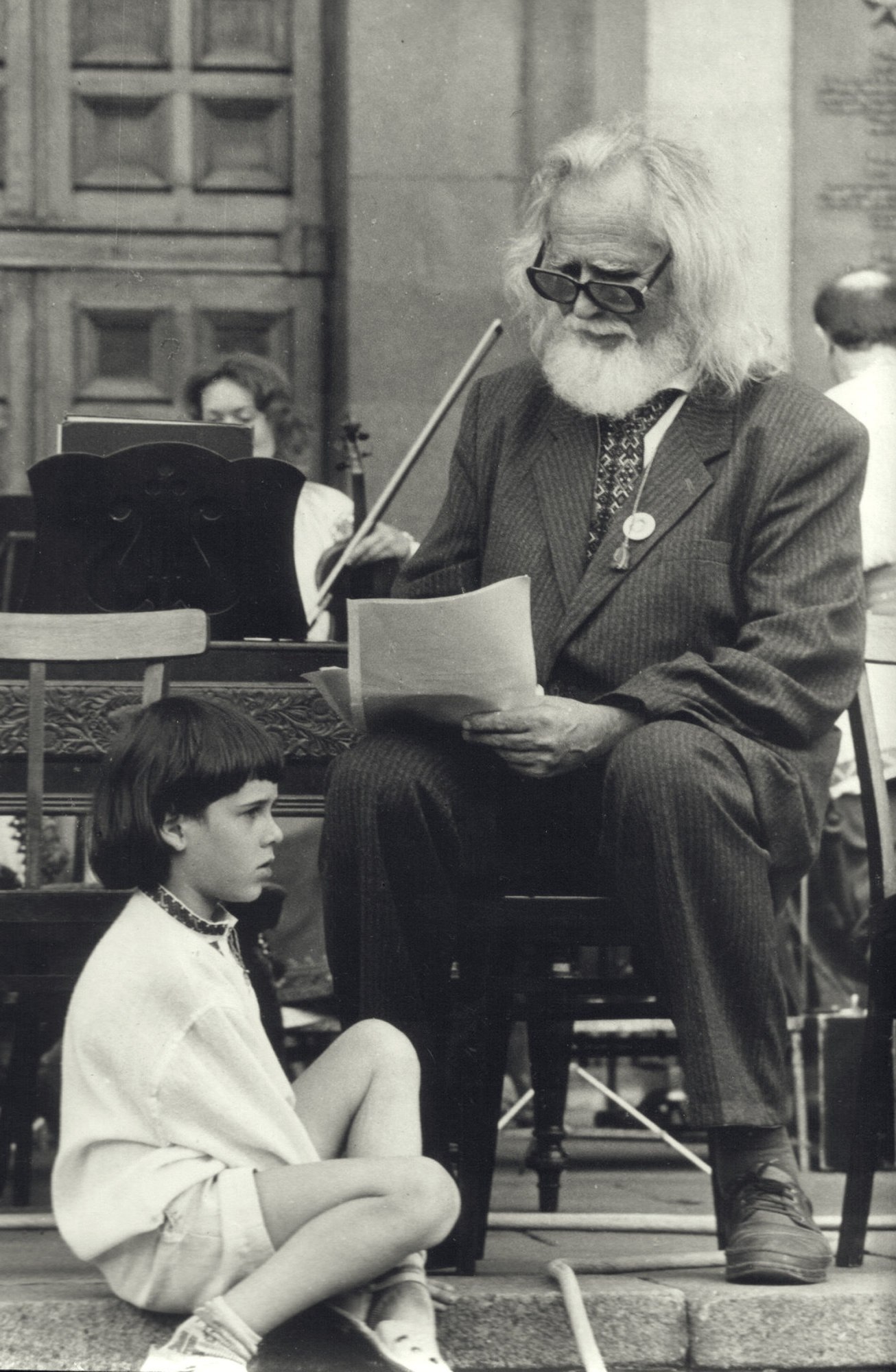

Oles Berdnyk, a co-founder of the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Group and a science fiction writer, at various ages. Photo provided by Hromovytsya Berdnyk.

6.

Scattered around the regions, the participants worked together on the documents. Some saw each other in Kyiv or Lviv, some visited those who were not allowed to travel. They met with former prisoners and relatives of those still in captivity to make lists, obtain testimonies about the conditions and stories of persecution. Those who had already returned brought notes from the people who remained in the camps. They then passed all this on to the West—to foreign governments, and European bodies, such as the United Nations. They reminded that in the Soviet Union there were constant searches, there was no freedom of religion or speech, “untrustworthy” people and their relatives were fired and persecuted. There was little reaction from governments, but the reports were at least read by foreign radio stations. So people heard about it.

The work of Rudenko and “like-minded nationalists” was hostile, slandering the Soviet system in front of the West. Such messages were passed on in classified reports by the KGB. They watched, listened and concluded: the Ukrainian Helsinki Group was controlled from abroad. Today, members of the group would be called “Soros minions” or “grant-eaters.” Less than a month had passed since the group formation, but the “possibility of arrest” was already discussed in operative notes.

In the first years, despite the fact that the members of the group disappeared one by one behind the walls of the camps, they succeeded in issuing several dozen documents on the persecutions. They were re-written and retyped using typewriters obtained from God knows where. Lukianenko even learned to work with handwriting and pressure. When they were declared criminals, he thought, the graphologic examination would at least not be able to prove that any of them had written it.

7.

When their political trial began, the telephones in their apartments often did not work. They were cut off by special services so that the group members could not coordinate and pass information to each other.

If there was a connection, the duration of the conversation depended on the third person on the line, who could at any time disconnect the subscribers “operatively” as soon as something was said that they did not like. Nadiia, Lukianenko’s wife at the time, said that she sometimes allowed herself to joke while talking on the phone. She lowered her voice, as if she had to convey something quickly. And then she revealed her pickles recipe.

The letters were examined, the packages were opened. Nadiia mentioned that she hid secret notes in her braided hair. And took them to Kyiv. If they stopped her to carry out a search, she had to shout and swear, not to let them do it.

Strangers could be dangerous. When the group members returned from visiting their parents in the village, an undercover driver could stop and offer a ride, Lukianenko’s brother recalled. A wife of a former political prisoner should have been careful when a Ukrainian-speaking man, allegedly a fellow countryman, met her on vacation in Sochi. Especially considering it usually took years to obtain a vacation voucher, and then all of a sudden she was almost forced to go to the resort by her employer.

They had to mind what they said in their apartments. Once the Rudenkos were called to the city offices for the whole day, and when they returned, they learned from their neighbors: plumbers were working all day in the attic above their apartment. What could plumbers have been doing in the attic when their work should be in the basement? Plaster had cracked on the ceiling from their work, and a microphone was carelessly hidden under the ceiling.

Mykhailo Horyn’s wife found a similar carelessly installed wiretap in her apartment. She dug it out of the wall with tongs. In the 1990s, Horyn learned about himself from KGB documents: the officer responsible for the sloppy installation was later punished.

What did the KGB hear? At the Rudenko’s apartment—conversations with Mr. Terelia, who in his works described the “horrors of the camps,” and was ready to kill members of the KGB: “I know. At lunch they all go to the café on the other side of the street. I would throw an anti-tank grenade at them and walk away. I will take revenge on the authorities. I have the right to do so.”

Regarding the Kyivan Yurko Badz, they wrote: he approves of the group and “if he had not been busy preparing an anti-Soviet document, he would have joined it.”

Within a month of the creation of the group, the KGB began preparing simultaneous surprise searches in all regions. They found pornography at Berdnyk’s apartment, German weapons at Tykhyi’s apartment, and US dollars at Rudenko’s apartment. Imprisonment for porn, weapons and currency is more sophisticated than for defending human rights.

Between December 22 and 24, 1976, 5,000 pages of documents were confiscated from those involved in the group. In secret notes, the KGB admitted that it was risky to imprison members of the group. This would definitely increase its activity, but experience had told them that the rebellion would be short-lived. There were more risks if the activists remained at large.

Since then, searches became constant. One of Oksana Meshko’s searches began with a broken window through which they entered. A personal search was conducted by force. The investigator held Oksana, and two women searched her. Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska, the niece of the classic writer, had her shoes searched. Mikhailyna did not belong to the group, but was friends with some of its members. The KGB pulled the insoles out of her old boots, and dug out the declaration of the Helsinki Group from under there. Petro Vins, a new member of the group, had 134 copies of the Tips for Relatives of Prisoners booklet.

Rudenko and Tykhyi were the first to be arrested as “the most fanatical,” and were then followed by others. For a few days, Rayisa did not know what happened to her husband—she was not even allowed to leave work to go to the prosecutor’s office. Nor was she let in the pre-trial detention center for several days to hand over food and clothes. When they finally let her in, they immediately took her away for questioning. They did not specify why her man was arrested. The investigator said: “There is nothing you need to know.”

8.

Myroslav Marynovych and Mykola Matusevych were the youngest members of the group. They were under thirty, the age when the others were sentenced to their first terms. In their memoirs, both confessed that they joined the group to rebel against Soviet life. Their families knew all about this life. They themselves had already experienced problems at school and work, for example, because of Christmas carols.

In a bid to destroy the group, the KGB tried to recruit the youngest boys as “spies.” After Rudenko and Tykhyi, Mykola and Myroslav were taken to the detention center in April. At the same time, the KGB, through their agent assets, suggested to the group participants that it was all a KGB campaign—and now the “spies” were repenting and betraying the rest. Thereby they planned to demotivate the group so that information about the arrest of these two would not reach the West. Both pleaded not guilty and were sent to the camps. Years later, Matusevych refused to be granted amnesty until he was fully exonerated.

When the first ten people were almost all in a pre-trial detention center or camps, others began to join the group one by one. Mykhailo Horyn, as promised, set to work and issued the group newsletter. In the basement, together with his wife, he copied the pages. He knew: this was the time when one should not leave the house without a towel, a bar of soap and a toothbrush. One day he forgot and went out with a suitcase full of materials from the human rights group.

9.

Many members of the group met at the Kuchino political camp in the Perm region. Other dissidents joined the group there who were imprisoned for other reasons—writings, poems, books, articles. Dissidents Valeriy Marchenko, Vasyl Stus, Yuri Lytvyn, and Oleksa Tykhyi died in this camp.

After the Gorbachev amnesty in 1987, those who survived returned to Ukraine. The Helsinki Group was transformed into the Helsinki Union. They continued their work. They became symbols. Lukianenko wrote the Act of Declaration of Independence of Ukraine on his birthday.

Some people gave it all up because they didn’t want to join government agencies, and decades spent in camps led to a deterioration of health, abilities, and sometimes common sense.

They will have a meagre pension to live on, at best. Some will go from government agency to government agency, in search of justice.

Investigators, KGB officers, and judges will generally carry on working in peace until their retirement, and receive a good pension.

But not all of them will be so lucky. For years, KGB Major Herasymenko was investigating Lukianenko’s entire family—his wife, brother’s and sister’s families. He treated them with disdain, in conversations he was contemptuous. He used to tell Lukyanenko that there were only a few people like him, while the whole nation was in support of the system.

When the KGB was disbanded, for some reason Herasymenko put on the uniform of a guard at a Chernihiv museum, although investigator Tonkoshkuryi was re-certified and went to serve in the Security Service of Ukraine. Several years later, Herasymenko had to guard an exhibition about Levko Lukianenko and other dissidents.

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More