The Laconic Peninsula

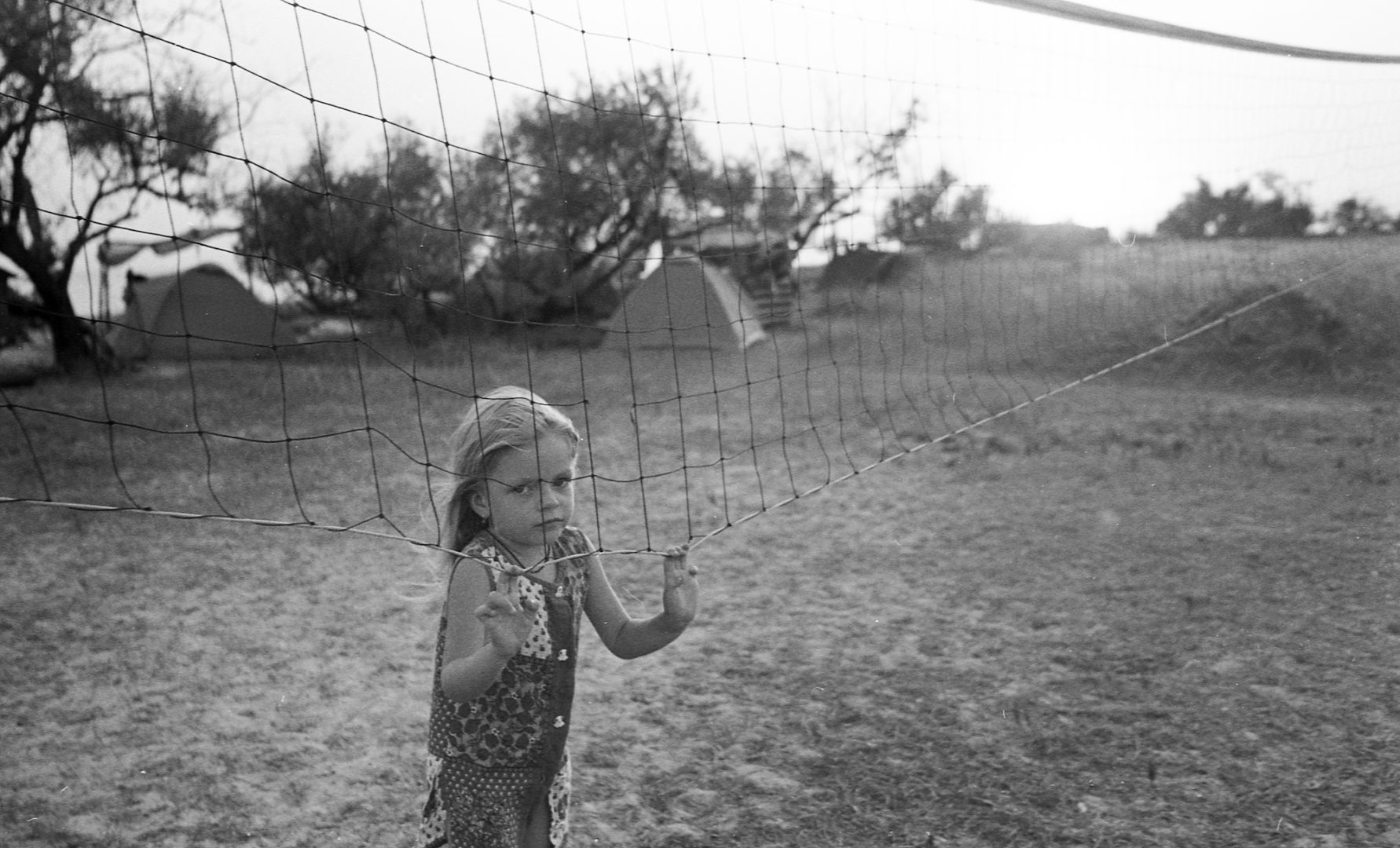

“Dad, I’m bored. I want to go home. All the friends I was catching shrimp and playing in the mud with left this morning and I’m afraid to talk to those Christians. When can we go?

“One more week, Son. I’ve only just begun to exhale the city.”

In the Christian encampment, kids are singing to the guitar. But I know that they don’t have any bug spray, so they won’t last long and will leave soon. And then it will be quiet again.

Five years ago, when I first brought my son Yehor to the spit he was six. For us, like for many Ukrainian families, the opportunity to go to Crimea vanished by default with the start of the war. After the mad jump in exchange rates, Bulgaria wasn’t much of a bargain either. So I remembered Kinburn.

I first heard about this place from my friend back in 2008.

“It is completely wild. We’ll be going along the beach and not seeing anyone. You have to walk four hours to get to the closest shop.”

“That can’t be. Is it heaven?”

“You’ll see.”

2008:

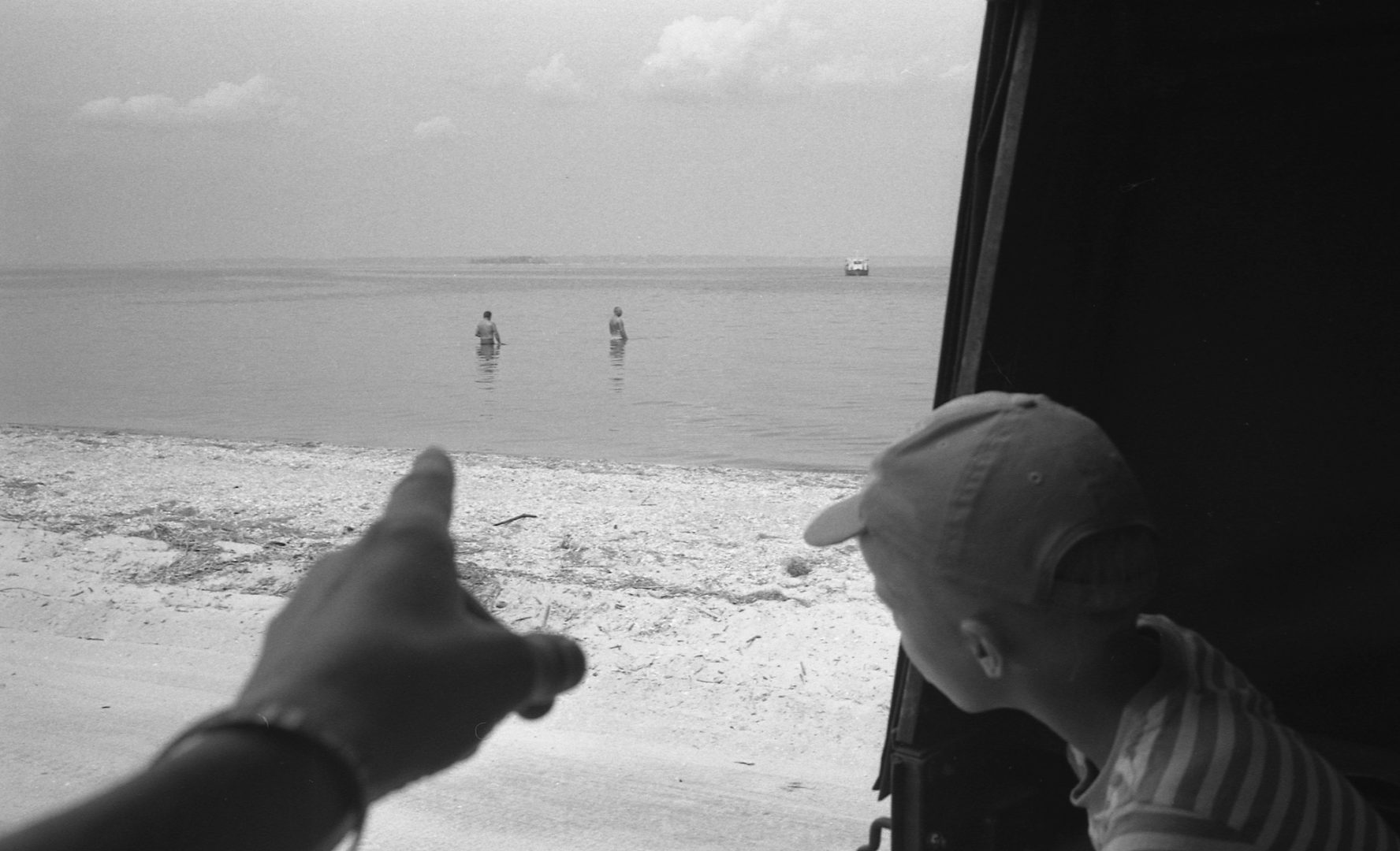

Two days later after hours of traveling in buses baked by the sun to the tiny, sleepy town of Ochakiv, a small motorboat carried us across the liman along Maiskyi Island. In the 18th century, serfs created it by hand on pilings driven into the bottom of the Southern Buh. They used to intercept the Turkish fleet here, and later it was a base for underwater swimmers, or “seals” in today’s parlance. From the boat I could see concrete piers almost completely covered in a layer of bird droppings.

The Kinburn spit is visible on the horizon. The incredibly long peninsula of sand and pines is half in the Kherson region, half in Mykolaiv. The ribbon of land gradually gets closer and soon the contours of the rusty body of some half sunken ship converted into a dock come into view. Crates of canned food and packages with soda and beer are unloaded from the motorboat. There aren’t any shops that can afford to ship in food and alcohol over land from the Kherson region across forty kilometers of sand. So everything comes by water and costs two or three times more than on the mainland.

The sea was waiting on the other side of the spit. There were three kilometers of sandy dunes and absolute silence to get there. Once there, taking photos of the remains of old boats, I realized that forty minutes of sand was what I paid for infinity. Everything was exactly like my friend had said. Wild

Back then in 2008 after hours of wandering around a deserted village we “surrendered” to a gray-haired local.

“Where can we rent a room around here?”

“Fuck knows.”

“What about from you?”

“Nah. But you can pitch a tent in my garden. No one will steal it.”

We could have pitched our tent near the sea. But no one did that because the foresters and border guards could simply take it as proof of a crime—spending the night in a national park. So we paid the greyhair 150 hryvnias and for three days slept among watermelons that were soaking up the sun in a small melon field. As a bonus we had the right to shower and use his kitchen.

The sea was waiting on the other side of the spit. There were three kilometers of sandy dunes and absolute silence to get there. Once there, taking photos of the remains of old boats, I realized that forty minutes of sand was what I paid for infinity. Everything was exactly like my friend had said. Wild.

However, there were people around. But there was at least a kilometer between the vacationers, no less. Any closer there would have been somehow uncomfortable.

On the first day we walked three hours in one direction and then we saw a colorful spot on the horizon. In half an hour it turned into a lonesome children’s blow-up pool. The water in it was practically boiling. There wasn’t a soul in sight. Two more hours later, our baked bodies led us to a mirage: a beer stand. Two “Yantar” umbrellas thrust into the sand near the obelisk tomb of an unknown soldier. The beer was warm but still delicious. The empty coast stretched on.

The next day we went in the opposite direction, away from the boats. After three hours we came upon a large iron dock that no one tied up to anymore. In the nearby forest, an inoperative resort was moldering away. But by some miracle, it had a working store with electricity and cold beer. Somewhere deep down I realized that I hated all of this. It was the hatred of Robinson Crusoe. Hatred for the place that does away with all romanticism, forcing you to wander for hours and greedily take everything that the laconic peninsula offers.

“Son, close your eyes. Open them when I tell you.”

“Ahhhhh!!!”

“I said when I tell you! Go rinse them in the sea.”

2015:

Now it is 2015. Bug spray in your eyes stings like crazy, but it lets you survive the evenings. The kids who have by now become kids of the spit, learn this fast. When the sun goes down, the squeaking bloodsuckers descend in a dense cloud. After an hour they disappear. This is what you pay for life in a tent.

The tent camp is located almost on the shore. We came here to try overcoming my hatred for this place. We reserved full room and board. A tent for two with my son. Two sun-faded cotton mattresses, which we must daily shake sand from. Three squares a day. All this luxury is 270 hryvnias per day for two.

I used to wake up in the morning, set my portable solar battery (it’s impossible here without it) on the sand and go to the “kitchen” where two enormous women had already boiled water for coffee. From seven o’clock on I had a whole hour to myself to drink my coffee and read a book. Then the heat set in and Yehor woke up. And everything started all over:

“Dad, I’m sick of being here. Let’s go home…”

He found friends here, then they left and he had to find new ones.

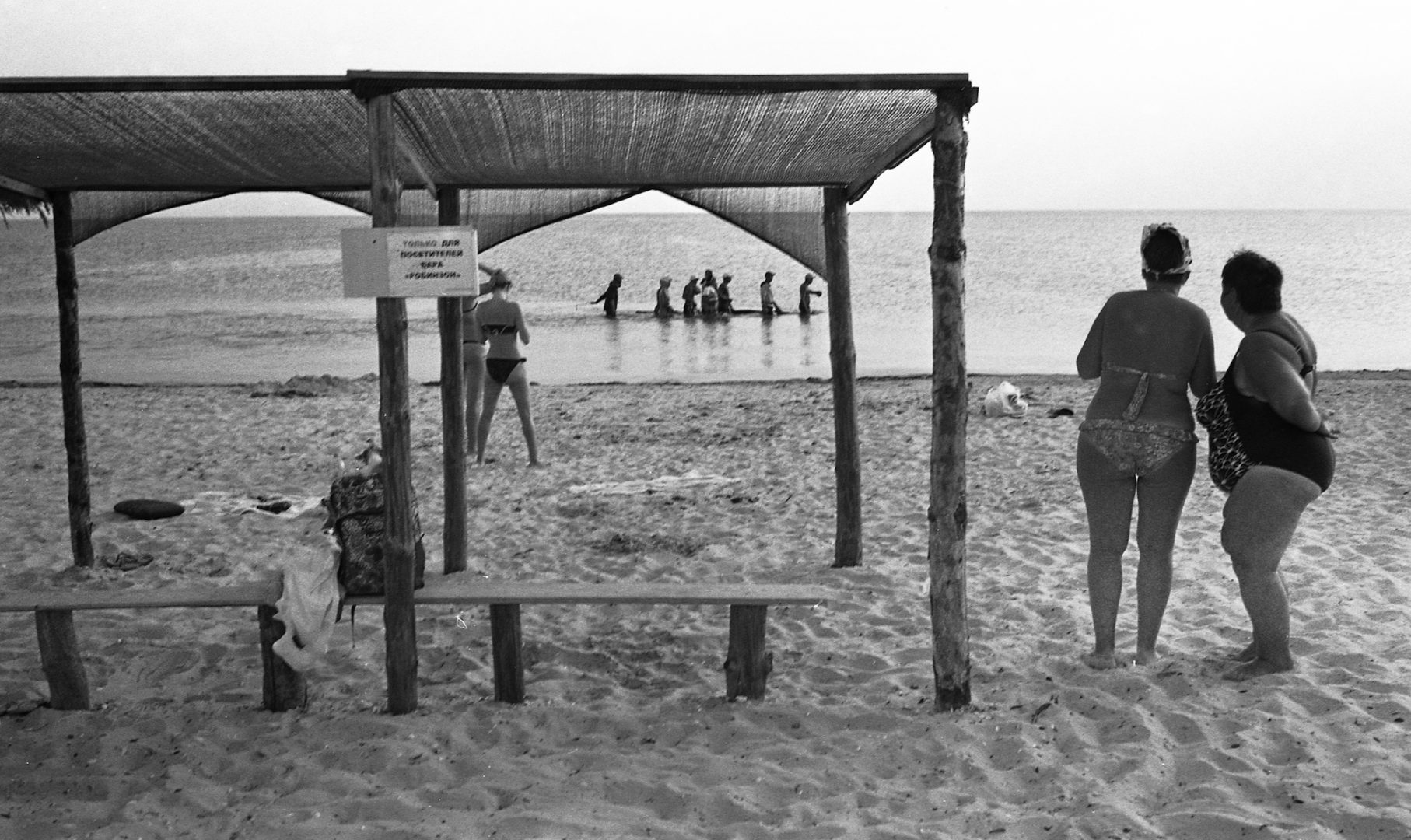

The spit in 2015 wasn’t quite as wild. Sitting near the sea, twice a day you could see a group of scrawny men and women pulling a sizeable tree trunk on their shoulders. The one in front gave the commands.

“Druggies. They’re driving their demons away,” one of the camp cooks revealed the secret.

About eight kilometers down the shore is a camp for drug addicts. They don’t come here to relax. But I can. Thanks to the scorching stillness full of the chirping of cicadas, thanks to the surprisingly cold sea and jellies that must be floating here to die, I slowly got used to this unhurried rhythm. It’s only a forty-minute walk from camp to a store, and there you can buy almost everything. Next year you’ll just need to bring your tent and cook everything over a fire.

Once we baked an injured seagull in foil and ate it, lying to the kids that they were eating chicken. We live in tents, wigwams, or simply in sleeping bags on the sand. We simply live, ceasing to be journalists, bankers, lawyers, or the local crazies

The village cafe has borshch for lunch and my hatred smoothly dissolves in the borshch, and the beer, and the beautiful people living in the neighboring tents, drinking wine around the fire on the beach at night and eating seafood they buy from the carefree poachers. They come onto the beach at night in old Soviet jeeps and pull gigantic nets into the sea that fill up with shrimp in a few hours. In August, the water in the sea starts glowing at night from the dying plankton, and we swim in this glowing nighttime cosmos.

“Son, just a few more days. I’m not ready to leave. I still haven’t taken it in.”

2017-2018:

2015, 16, 17, 18, 19—every year we set aside 10–12 days to come here and take it in. We’ve made friends we’ve had for many years. Our children have grown up here. Now they can go to the village for groceries themselves, and argue over whether to choose chips or a can of kvass. We run barefoot along the beach, fly kites, and shoot from bows. We bear electronic raves that soon pass because the ravers don’t have bug spray.

Once we baked an injured seagull in foil and ate it, lying to the kids that they were eating chicken. We live in tents, wigwams, or simply in sleeping bags on the sand. We simply live, ceasing to be journalists, bankers, lawyers, or the local crazies. Before we return, we traditionally ask each other not to post all of this on Facebook in order to keep this corner for ourselves.

But it’s too late. The spit is changing.

Practically every local villager has built guest houses along the shore of the estuary and offers green tourism. Now it’s not just addicts who come here to drag a log in a friendly group. People come with portable speakers in jeeps and buggies whose engines screech on the beach at night. They all bring their own understanding of vacation and our ideal model of wildness is bursting at the seams.

2019:

Like native Americans, we have been left a few “reservations”—camps on the seashore where guests are taught to handle this narrow strip of sand with care. The camps have clean water and some food; here you could be asked to pick up that plastic bottle you left on the beach or, if it happens again, to gather up all your things from the camp and yourselves along with them. But these camps survive on the shore on sufferance contrary to the general course of the spit’s development.

It’s not Zatoka yet, but in about five years they’ll probably lay asphalt and open up hotels. And there will be rows of chaise lounges on this sand where the vacationers will forget their hotel towels.

The Kinburn spit is perhaps the largest sandy seashore in Ukraine. So, yes, the state should make wise use of it, letting some relax, others make money, and the local coffers fill up. However these quick changes pain my heart. I’m glad that building a road here would be unfeasibly expensive for the state, since this carves out a little more time for people like me. Time to take it in.

Translated by Ali Kinsella.

[This publication was created with support of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Norwegian government].

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More