The Guides

Winter, like a real one. No, it is indeed the winter of 2022. January. Two women get on an old motorcycle with a sidecar near a shop in the village of Mala Obukhivka. Both are a little tipsy. “Fly!” resolutely orders the bigger woman.

The smaller one obediently starts the engine, and the motorcycle takes off into the night sky, cawing like a crow.

“Fuck me, Ninka, we are flying on no gasoline!” wonders the one behind the wheel.

And they fly on, astonished, in the night sky over Velyki Sorochyntsi, Dykanka, Myrhorod, and Shyshaky. For where else can two attractive women do some flying on a motorcycle than in Nikolai Gogol’s cosmos? They fly over houses and cemeteries, shiny silos, and gas stations, where lonely attendants follow them with their longing eyes; they fly over the resorts of Myrhorod, over the rivers of Psel and Khorol. They avoid the churches because it is not much Christian to fly like that without gasoline. The snow hits them in their mugs (as they mercilessly call their beautiful faces) and blinds their eyes. Yet they know where they are headed. They have a goal, and that goal is revenge for a betrayal. But that will be another scene, and this one. . . Cut!

I won’t tell you that we are shooting this flight very conditionally, some of it on a “green screen” (a backdrop against which footage is shot and can later be superimposed over any background). The actresses’ hair and clothes are waving because of the wind machine. Part of the scene is shot on a platform (a special trailer carrying the motorcycle and making it look like driving and then flying in the frame). If you find out about these things, then the magic of cinema will get lost, and you don’t want to lose it. The film is called The Demons and has many film tricks and illusions, except for the main thing—it is shot in the Poltava region near Myrhorod, in authentic villages, precisely per the script.

Filming on expedition warrants. . . no, not a success; we don’t know anything about that yet. It warrants that the local gods and demons will undoubtedly join the process. They will help, hinder, and dictate their own terms. Filmmaking will become a joint business with them. And one of the most famous gods or demons of these places is, of course, Gogol. The inspirer and provocateur. He marks his presence in everything, starting with jokes and ending with the tragic and majestic death of the actress.

Having thrown in our lot with him, we agreed not only to his gifts but also to the fateful course of events, discomfort, and challenging questions. And we have gotten his complex universe—with mysticism, the influence of Russian culture, irony, madness, and self-immolation. He spoke to us through the guides: people and phenomena that appeared inside and outside the frame. We met some of them long ago, others during the shooting. I will tell you about a few.

“Yermakov speaking,” or The Fleas of Love

It was the real summer of 2016 in a village on the Psel, with swimming and mosquitoes, relatives and barbecues, and hangovers and epiphanies. One day, exhausted from rest, we decided to go for a drive around the area. At first, we drove on “paved” roads, where fillings fall out of teeth because of the potholes. Then we turned onto gravel roads, followed by sands, paths, and offroads. We drove through half-abandoned hamlets and villages—Mala Obukhivka, Sakalivka, Olefirivka, Panasivka. . . Some of the places were new to me, and I could never imagine that, five years later, I would return there to make a film. But back then, we drove, amazed at our discoveries. The hamlets were almost deserted, uninhabited. Every one of them only had a monument to the Unknown Soldier, still standing in front of dilapidated clubs or village councils, as if testifying that people had once lived there and had not forgotten someone. It seemed that all the inhabitants had died in some unknown war, and the monuments were there to commemorate them. Nature was taking its toll, quickly absorbing the signs of the human world. It was only sand and pines, beauty and sadness.

Suddenly at the exit from Panasivka, something strange appeared on the horizon. I even thought it was a mirage. There were some frozen figures along the road getting ready to check our documents—maybe they were the Unknown Soldiers of the Poltava region gathered for training?

We discovered it was a sculpture park—an incomplete yet impressive set of Gogol’s characters and their predecessors from Greek mythology. Pan was playing his pan flute, Vakula was taming the frightened devil, naked mermaids were seducing, the young lady would soon drown, and Venus had already taken her bath. And all of that was knee-deep in unmowed weeds.

We stopped and got out of the car. Amidst forest and silence, there was a courtyard with a painted gate. The yard was empty—there were no chickens, pigs, or seedbeds. But the house was intact, with the Ukrainian flag atop. Some mangy doggie was grinning amiably from afar. Apparently, we were just living sculptures for him. We dared to ring the surprisingly working bell on the purely notional gate. A small thin man came out of the house, introducing himself as Valeriy Mykolayovych, the owner and author of the sculpture park. He spoke Russian and was born in Russia, but he worked in Poltava as an engineer all his life. Yet that was a long time ago. Now he was living there. Painting and sculpture were his hobbies. He did not consider himself an artist, sell his paintings, or accept any help, God forbid. He was proud as a turkey.

He let us into the house—a genuinely monastic cell. His wife had died a year before, leaving behind her houseplants ruled over by a huge Swiss cheese plant that had ousted the artist into the corner of the room along with his cot. The whitewashed walls were densely covered with his paintings—primarily allusions to Greek mythology, but all against the background of his native willows. There were some small sculptures on the veranda: Cupid, Natasha Rostova, Demon, and others. Among the signs of civilization, there was a radio. In a few years, he would get a TV. Valeriy Mykolayovych would switch the channels with a walking stick and curse it because the TV would take up his precious time.

This acquaintance continues to this day, using the phone (“Yermakov speaking”) and our summer visits. I begged him to paint something for me. He called the painting The Pleas of Love. My mother misheard it as The Fleas of Love, so that’s what we call it now. The Fleas starred in the series To Catch the Kaidash, and the fact was made known to the artist by attentive fellow villagers (he did not yet have a TV at the time). He painted it on an ordinary sheet from a Chinese bed set sold in our markets. The painting depicts six women in tunics, with Venus in the center. Their faces are ours, Poltava faces.

In 2021, when I started working on The Demons and was thinking up the scene with a summer village market, I immediately imagined our artist there with his works. The camera quickly passes him, but you can pause and look closer. We placed Pan on a pedestal of Lenin, and the paintings leaned against the obelisk of the victims of WWII. Yermakov was sitting in the center instead of the Unknown Soldier.

If you visit him today, bring some paints and canvases as a gift. And a bottle of red semi-dry. Unfortunately, you will not see most of his sculptures and paintings—he has donated everything to local schools and sanatoriums, so we had to collect his works for the film from around the region.

Nobody fancied one of the female sculptures because it was too big. Sculpting it, he was inspired by the image of Julia Roberts in Pretty Woman. So now Julia is sitting on a bench in Panasivka with naked breasts and a bottle of vodka and is patiently waiting for you.

Idols and prostitutes

In addition to monuments to the Unknown Soldier, every village had a monument to the well-known Lenin. Then, one day they all vanished. I never really wondered where until I realized there should be such a drifting Lenin in my film about the 90s. Sometimes he would stand on his pedestal, and other times he would get scared and run away. Later he would return and stand for a while in hope. Then he would get off again and leave. We went looking for him and found this: Lenin was safely hidden and guarded on a remote farm in one of the villages. He was, however, repainted yellow and blue—well, just in case. Lenin’s guard, a man black from vodka, gloomily said: “And who was he harming there by the club?!”.

We wanted to bring that Lenin for the film, but he turned out to be too heavy to lift, which supports my theory that they ran away from their pedestals on their own. Therefore, we had to make him out of paper-mâché. Later, mice got inside and ate his left arm and half of his head.

For the scene in the club, I needed different portraits of Gogol. And I recalled a strange, crazy artist in the partially occupied Shyshaky. He paints primarily nude women on plywood and then cuts them out like we used to cut paper dolls as children. The curvy women in exciting poses have long eyelashes and carefully traced details. He also created Gogol from plywood—dressed, wearing a weird hat, but very feminine and seductive (pardon me, Mykola Vasylyovych). The artist passed the casting, but he had one condition—we could take his Gogol only with the prostitutes. So we had to film them all.

Why is Shyshaky partially occupied? Well, because it has long been a fashionable place among Moscow bohemia. They bought houses there for next to nothing, built bungalows and cottages, and ruled there every summer, even after 2014. The only thing is that, after 2014, upon arrival, they put on necklaces with a trident—well, just in case. Ukrainian villagers greeted them with bread and salt, willingly cooked, built, cleaned, and guarded for them. Now Moscow bohemia are probably singing the popular song “I Hate to Leave” Shyshaky.

Witches and deacons

A Ukrainian сountry woman is, of course, a phenomenon—“I’m no feminist, God forbid, but everything will be my way, and I said so.” But she has come close to her true independence only recently. And no politics or revolution, not even the internet, liberated Ukrainian country women. It was a scooter. For ages, these women suffered, having to depend on Tolko, Yurko, or Mykola to take them somewhere. And men always had more important things to do. So finally, women discovered an inexpensive broom that required no license—just buy one and fly. And now these independent witches fly around the villages on their modern brooms, singing the folk song “I Don’t Need That Alcoholic Anymore.”

I came up with the idea that my heroine dreams of a scooter. There is a scene where three colorful, eye-catching women are riding their scooters “to the bazaar” (as they say in the Poltava region). And she is staring after them with an envious look. It was difficult to choose these three because every other woman in the village is a colorful witch on a scooter. Ultimately, I opted for my classmate Nina, my nephew’s wife Dasha, and the tractor driver Galya. Galya was famous throughout the region for her ability to drive all types of transport, from a scooter to a tank. But she did not wait for the tanks. Covid took her life in February. I am glad that we captured her bright, strong image.

Some five years ago, tired of monotonous summer days in the countryside, I attended a local cultural program. The meeting place was a bus stop, where a dozen formally dressed women aged 45-60 gathered to go on their “culture tour.” There were no men. The bus brought us to Sorochyntsi. The program consisted of visiting the famous local church built by Danylo Apostol, where Gogol was baptized, the museum of Gogol, and a party in a pub, the final and favorite part. In the church, we were told about the underground passages under the Psel River, the Hetman’s treasures, and the unique iconostasis saved from the Lavra scroungers.

In the museum of Gogol, we toured the empty rooms because the place had almost no exposition. However, this was compensated by theatrical skits from Gogol’s works performed by local amateur actors. There was a different skit in every room. I remembered the Deacon with Solokha and a scene from The Government Inspector, where my distant relative played the role of the policeman’s wife in hoop skirts, and Grisha, a tractor driver from Sorochyntsi, very enthusiastically played the role of Khlestakov. The performance was in Russian, but with such a sincere Poltava accent that it looked like trolling. The women laughed and applauded. For the first time in many years, I reсalled that I loved theater, not experimental, modern, or relevant, which I have been into all my life, but the one like this—basic and honest.

In the pub, we drank moonshine, ate varenyky and cabbage rolls, blood sausage, and saltison, and sang sad and bawdy songs. I remember all these women from my childhood, and they have changed so imperceptibly that they have not changed at all.

It was comforting to be in their company and feel temporary immortality. Later, I involved some of them in the crowd scenes. Those whom I did not invite were offended. Now I hide in the bushes every time I see them.

And last year, while looking for actors for the film, we came across another treasure theater in Myrhorod. Actor Ruslan Harmash was cast in a major supporting role, we engaged most of the others in episodes, and they filled the film with life and organicity that I could have never dreamed of. In our film, Ruslan plays the role of a tempting demon, but in real life, he is kind, cheerful, hardworking, and doesn’t even drink. Every year at the Sorochyntsi Fair, he always plays Gogol’s Deacon. Soon our directors will be fighting over him, as well as over Alka-The Catastrophe, who played the seller of knives.

During the filming, the Myrhorod land opened up sincerely and deeply to our requests, and I am very grateful for that. However, this summer, for the first time in my life, I did not go there—as if, during that immersive expedition, I had earned an unplanned and unwanted vacation from my place of power.

Old Melashka, or “Why in the world have I let you in?”

It is the unreal winter of early 2021 because the only thing we are doing is working and worrying, not living these days to the fullest. Where are the ski trips? Where is the mulled wine at the rink? Where are the evening memories of summer? Where is Egypt, after all? Nowhere, because we will be shooting soon. We are looking for filming locations in the Poltava region. What we need is a picturesque yard, three of them, actually. But one must be truly extraordinary. As always, nothing fits. But then, lo and behold, in that same Mala Obukhivka, we looked into a street and found ourselves in another dimension. A large old house, wattle and daub, covered with reeds. There are no indicators of time, none whatsoever. True, there is no farmstead either. Yet the house is heated, so there must be a living soul. The yard is on a hill right above the Psel. Behind the river, there are endless meadows. In the yard, there are old sycamore and plum trees.

We went deeper into the street and found a man chopping firewood. A real man in a padded jacket and an ear-flapped hat, one ear flap sticking up. “Good afternoon, we are filmmakers,” we said. “Come on in, Natasha’s frying fish,” replied the man. So Vanya and Natasha became our guides and introduced us to Melania Hryhorivna, the owner of the picturesque household. Well, not exactly introduced but rather provided access to her portal.

Melania Hryhorivna had recently turned 100. She lived alone and had no family, as they told us on our way to her. We opened the ancient doors—the first one, the second one, with a creak. Inside the old woman’s house, everything was exactly as it used to be a hundred years ago.

There was not a single plastic item, not even a radio. I saw neither pills nor jars of Corvalol—these faithful friends of old age. Old Melashka was half-lying in a bed by a thoroughly heated stove and dozing off, for it was winter. For the winter, they warned us, the old lady goes into hibernation and returns to life in the spring. Last summer, she even planted a vegetable garden.

The house was clean and bright; there were embroidered towels, icons, and photos, where the living and the dead had long since faded. There were an ancient chest, a bed, and a table. That was all the furniture. The house had unusually high ceilings. “Dear God, where are we? How could it happen?!” I was thinking to myself. “How can you disturb this absolute harmony, breaking in with your loud and dirty filmmaking processes?” asked the human in me. “Are you a fool? Grab it! It’s pure luck. You won’t find anything better,” interrupted the vile director. Who won, you would ask? Cinema, of course. I guess art marks the end of tact and respect for other people’s lives and space.

The following summer, we returned with a film camp. We installed our equipment, constructed a veranda and shed, and filled it with props and animals. We put the dog named Moscow on a chain. Camera, action!

Old Melashka did not plant any garden that summer, but she did come out of hibernation, returned to life, and went up the hill every day to look at her garden, her Psel, and us. She was fully sane. During the breaks, I used to come up to her and ask her questions—well, I shouted throughout the entire village because the old lady had poor hearing. So, they took her husband to the war after the wedding. Then, she said, she lived alone. But her neighbors said that after the war, she lived with another man for about fifty years until his death. But somehow, she forgot about him. Instead, she remembered the one taken away on the third day after the wedding for the rest of her life. It happens.

All her life, she worked hard at a collective farm. In summer, after work, she would go and fall into the Psel—and soak. And then, at home, she would fall on the bed and wake up in the same position. And off to hard labor again. Maybe that’s why she forgot her husband or had no children.

She did not know how old her house was. It was obviously older than her. The previous owner, she said, was killed by some “Reds” or “Whites” when they were hiding in the forest. But he managed to hack one of them with an ax.

I dared to shoot one scene in her house. Luxurious Ruslana Pysanka was lying on a bench in a white shirt. The film crew stood in masks. Melania Hryhorivna was quietly sitting behind the camera crew, watching that movie, and who knows what she was thinking about us. From time to time, her shadow came into the frame.

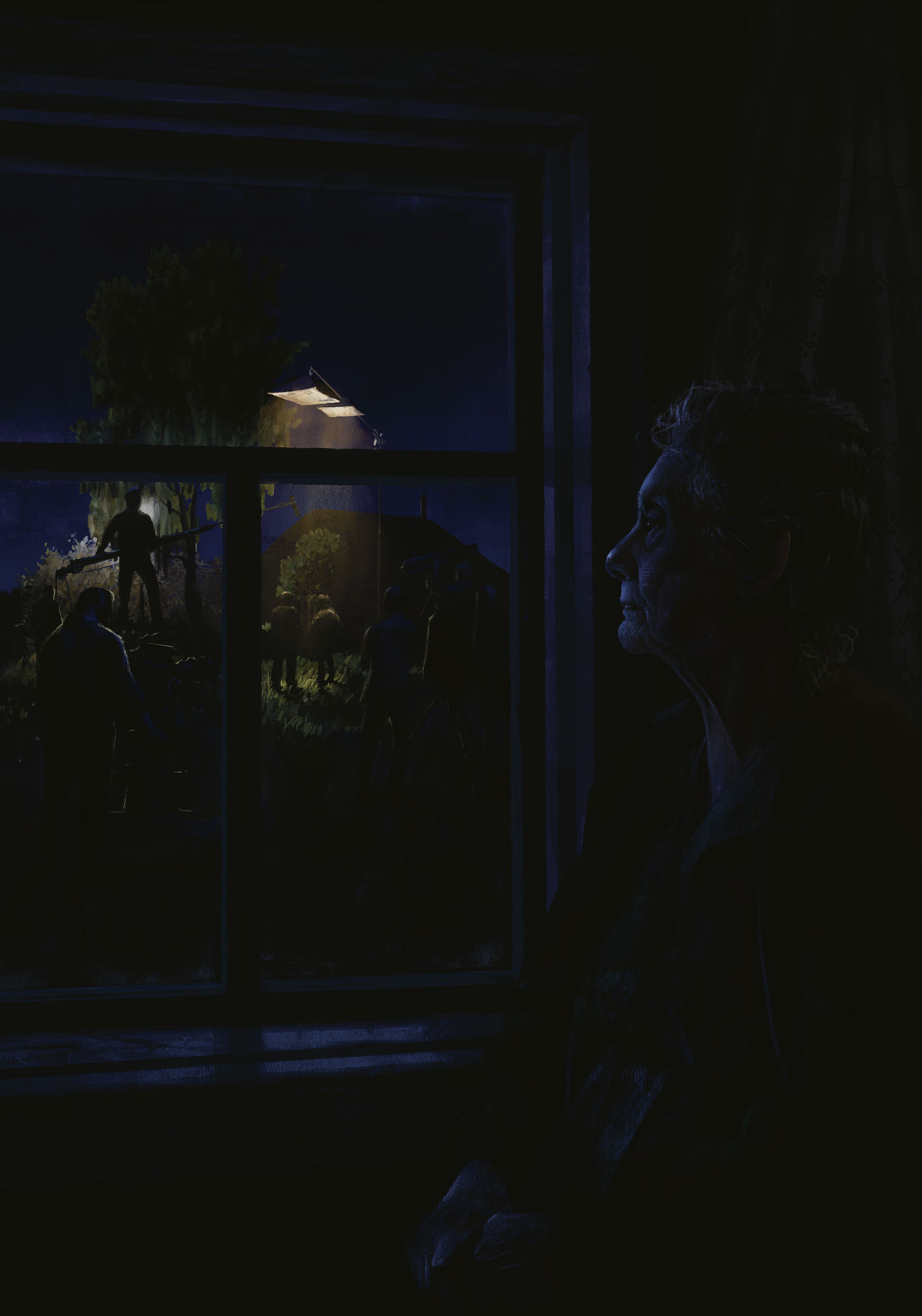

Or, as it happens, we were shooting a night scene. Artificial light flooded the entire yard. There were thirty people in our crew; it was showtime. Suddenly the ancient face of old Melashka looked out of the window, and everything happening was much more interesting than any cinema. “What if she gets into the frame?” someone wondered. “It will be a blessing,” I replied.

“Why in the world have I let you in?” she asked me kindly in the morning. “If only I knew, I would have never let you in. I’m tired of you.” Yet she happily took the money for the location and hid it somewhere in herself with the agility of a 17-year-old girl.

Or we arrived at the location and discovered that someone had cut down the cherry tree. Yesterday it was in the frame, and it had to be there the following day too. The art department was scolded, and the illuminators too. As it turned out, old Melashka thought that the cherry tree obstructed our work and ordered the neighbor to cut it down. Fine, we somehow tied it back to the trunk and shot the scene.

By hook or crook, I made Melania Hryhorivna sit on a bench while filming one scene. And now she is part of our cinema cosmos.

The last time I saw her was this winter—she was enjoying a plate of borscht from which a large cock’s leg was sticking out. The stove was well heated. This scene still warms me up. It also warms me that she did not get attached to or hate any of us. We were a part of the scenery for her.

She died this evil March at the age of 101. I don’t know if she knew about the full-scale war. She had no radio, no television, and no close relatives. And she only heard whatever she wanted.

Cherry pits

If I think back on my life from the beginning, filming The Demons was one of the destination points of my route. This route started one real, hot, careless summer when I was ten years old. After running around and having a good swim, I used to hide in the cool house with a cup of fresh midday milk and a cherry pie, lie down in a deep mesh bed, and binge-read the stories of a man with the funny last name Gogol. And more than one cherry pit dived somewhere between the blankets, and in the fall, it was shaken out at the doorstep and sprouted into a new cherry tree. So I read and re-read the works with the titles dear to my heart—Myrhorod, Sorochyntsi Fair, Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka. . . And I recalled my mother telling me about the blue-mouthed witch in a little window; and my grandmother—about a Canadian spy disguised as a woman who collected food in the village and then threw it away together with his parachute; and my grandfather—about a cannibal woman displayed in the zoo. And how someone in the village had stolen the moon. . . Everything read coincided with the overheard and seen, coincided with the place and the scenery.

Whatever they say about Gogol—that he created Ukrainian mythology, invented sharovarshchyna [derived from “sharovary”—a kind of wide men’s trousers, part of the national clothes of Ukrainian Cossacks,—this usually negative term refers to a way of representing Ukrainian culture and identity with the help of pseudo-folk peasant and Cossack clothing—R.], that he is a traitor,—he taught me to fly, to be ironic, to play with the underworld, to think broader. I see his profile on the wallpaper of my apartment; he safeguards my place of power, the Myrhorod land.

Our film has not been shot yet. Filming was supposed to take place in April. But then, instead of witches and Vakula, there were Russian rockets flying over Myrhorod and falling on the airfield. Gogol is also a bit to blame for this, but are we—together with him. For he is us. Well, at least me.

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More