Ten Minutes of Silence

Until recently, Mykolaiv was a quiet city in the south of Ukraine, with a peacetime population of nearly half a million. On one side, it borders the currently occupied Kherson, and on the other one, the port city of Odessa, which the Russians are also keen to invade. Due to its location, the city has been on the front line from the first days of Russia’s full-scale invasion: according to Oleksii Danilov, Secretary of the NSDC of Ukraine, Mykolaiv is the third most shelled city in Ukraine, with only Izium and Mariupol faring worse.

In the basement of one building located in the center of Mykolaiv, three volunteers play the Uno card game every evening. Their deck is twice as thick as when it was new, with the cards swollen from frequent use. The game at least briefly takes their mind off the stress of the constant shelling and news about yet another attack on the city.

“Here it comes!”

2.06: “Everyone, take cover! Air raid siren!”

2.10: “Missile hits coming one by one!”

2.10: “One more is coming! There have been 7 shots!”

2.14: “There are powerful explosions in the city.”

3.16: “Mykolaiv, air raid siren!”

3.18: “A missile hit!”

3.19: “Here it comes!”

3.19: “Here it comes again.”

3.21: “Another hit!”

3.25: “Another hit!”

3.26: “This was a heavy one!”

3.28: “Two more coming!”

3.29: “A missile is coming from the sea.”

3.31: “Seven minutes of silence.”

3.33: “Our eyes on the ground say: we have missile hits at the locations where you have been attacked from.”

3.39: “The Orcs are leaving their position.”

Such messages in Viber, sent during the night, are now quite common for Mykolaiv residents. From the beginning of the big war in February till the middle of July, the city had escaped shelling for only 21 days. As for the rest 130 days, air raid sirens have sounded every few hours and explosions have been heard across the city. Both official channels and volunteer chat groups inform on missile hazard. One of these chats has more than 85,000 subscribers. They include people from the occupied territories who monitor the movement of enemy groups, see with their own eyes when and where they launch missiles from, and pass the information on to the channel’s moderators.

59-year-old Zinovii, a local resident and, by chance and his own will, a volunteer, also monitors messages in this Viber group. His house is located in the very center of the city. The regional state administration is nearby, which was destroyed in late March by a direct Russian missile hit, burying 37 people under the rubble. Aware of how dangerous the situation is, during air raid sirens, Zinovii and his neighbors hide in a shelter that can be accessed from their building entrance.

“Our bomb shelter was not looked after. Before the war started, it had been cleaned a bit. People brought some old chairs from the neighboring school, an electric kettle for hot drinks. When it was 15 degrees below zero outside, it was only 6 to 8 degrees in the bomb shelter. You won’t last long under such conditions.”

It is still cool in the basement, but in early July it is a pleasant coolness. The basement contains several rooms, in one of them the floor is covered with blankets and sleeping bags. There are chairs and a table in the corner. The shelter is clean, with white walls and painted doors; there is even a sink for washing. For most of his life, Zinovii did repair and maintenance work, so making this neglected space livable was a matter of principle for him.

In the first months of the war, several dozen people hid in the shelter, and now there are three people left in the neighboring room and three in here: Zenyk (his wife and 13-year-old daughter recently left the city) and their neighbors, a married couple from the third floor, Ira and Ihor. They moved into the building only a year ago, and had plans to renovate their flat, but now they live with windows blown out by a shock wave.

“Make another move, Ira!” says Zenyk. By an impromptu tradition, during air raid sirens, they always play Uno. The goal of this game is simple—to be the first to get rid of all their cards. When you have only one left, you should warn the other players by shouting “Uno!” If you forget to do this, you have to draw additional cards. While playing, you have to be focused on what you and the others are doing—just like surviving in wartime.

“When the headquarters of the Red Cross began to set up in the city, we brought everything we had and that could be of good use: mats, sleeping bags, bed sheets. I brought all my yellow T-shirts to make armbands to identify our own side,” Zenyk recalls.

He looks like an intelligent man and speaks pure Ukrainian. He does this not only when talking to us—in almost 40 years in Russian-speaking Mykolaiv, Zenyk managed to preserve his everyday Ukrainian-speaking identity. He comes from Zhydachiv, a small town in the Lviv region. In 1985, he moved to Mykolaiv from Lviv, where he studied radiophysics. After he graduated from university, he was offered a choice of workplace in Kazakhstan, Rostov-on-Don, or Mykolaiv.

“I chose Mykolaiv because, like most people in western Ukraine, I thought that it was on the sea. But,” he laughs, “there wasn’t even a normal riverside beach here.”

But he stayed and over the years fell in love with this burning hot city in the south of Ukraine.

A city without a sea, but with a history

There really is no sea in Mykolaiv. But there are two big rivers: the Inhul and Southern Buh rivers, which merge right in the center of the city, and then descend down into an estuary and the Black Sea. The geographical location of the city was ideal for shipbuilding, and more than 200 years ago, the modern city was built around a shipyard. The narrative created by Russian propaganda was based on this, claiming that Mykolaiv was a historically Russian city, because it was founded by the order of Prince Grigory Potemkin, a favourite of Catherine II.

However, Ukrainian historians point to the facts of the matter: Ukrainian Cossacks had inhabited this place long before that. Moreover, around 1250-925 BC, the city of the Cimmerians stood on the territory of modern-day Mykolaiv: an ancient port city built by the Cimmerians of the Belozerskaya culture. It is one of the oldest recorded Ukrainian cities.

“The myth that this land was empty before Catherine II’s decision to found the city is popular in Russian narratives and even runs through Ukrainian historiography,” says Yurii Kotliar, Doctor of History and Professor at Black Sea National University. “Bit by bit, we are collecting evidence about the ancient history of the city. But the fact is that the documents related to the ancient history of Mykolaiv were taken from Ukraine.”

“The history that we can trace through the archives is the end of the 18th century. Russians always do this—they take some part that is beneficial to them and focus only on that.”

Based on materials collected in the south of Ukraine, Yurii has written a thesis paper on the insurgent and partisan movement of Ukrainian peasants in 1919-20. In our conversation, he also mentions the events of the Vradiivka Republic.

“It was not a proper state, but rather an attempt of the local population to self-organize in times when the central authorities were constantly changing. However, the Vradiivka Republic,” says the scientist, “claimed it was supporting the UNR Directory and was against the Bolsheviks. It was absolutely pro-Ukrainian.”

The enemy is shelling residential areas

“Here, the Russians are on foreign land, they don’t care about anything,” says Vitalii Kim, head of the Regional State, now the Military Administration and a favorite of at least 800,000 Ukrainians who subscribed to his Telegram channel. “We cannot shoot at buildings, because they are all ours, we built them. But they don’t care, they are invaders.”

The head of the RMA is a charismatic 41-year-old man. He is not as funny in real life as in many of his videos. Kim is reserved, serious, sometimes sharp and terse. However, when it comes to his hometown, he says that he loves it.

“We managed to move in a lot of weapons quite quickly. When the Russians invaded, our territorial defence forces, patrol police, special operations forces, and the military all had manual anti-tank grenade launchers and machine guns, so we had something with which we could repulse them,” Vitalii explains why the Russians failed to seize the city in the first stage of the war. And he jokingly adds that the real reason is that shipbuilders are really tough.

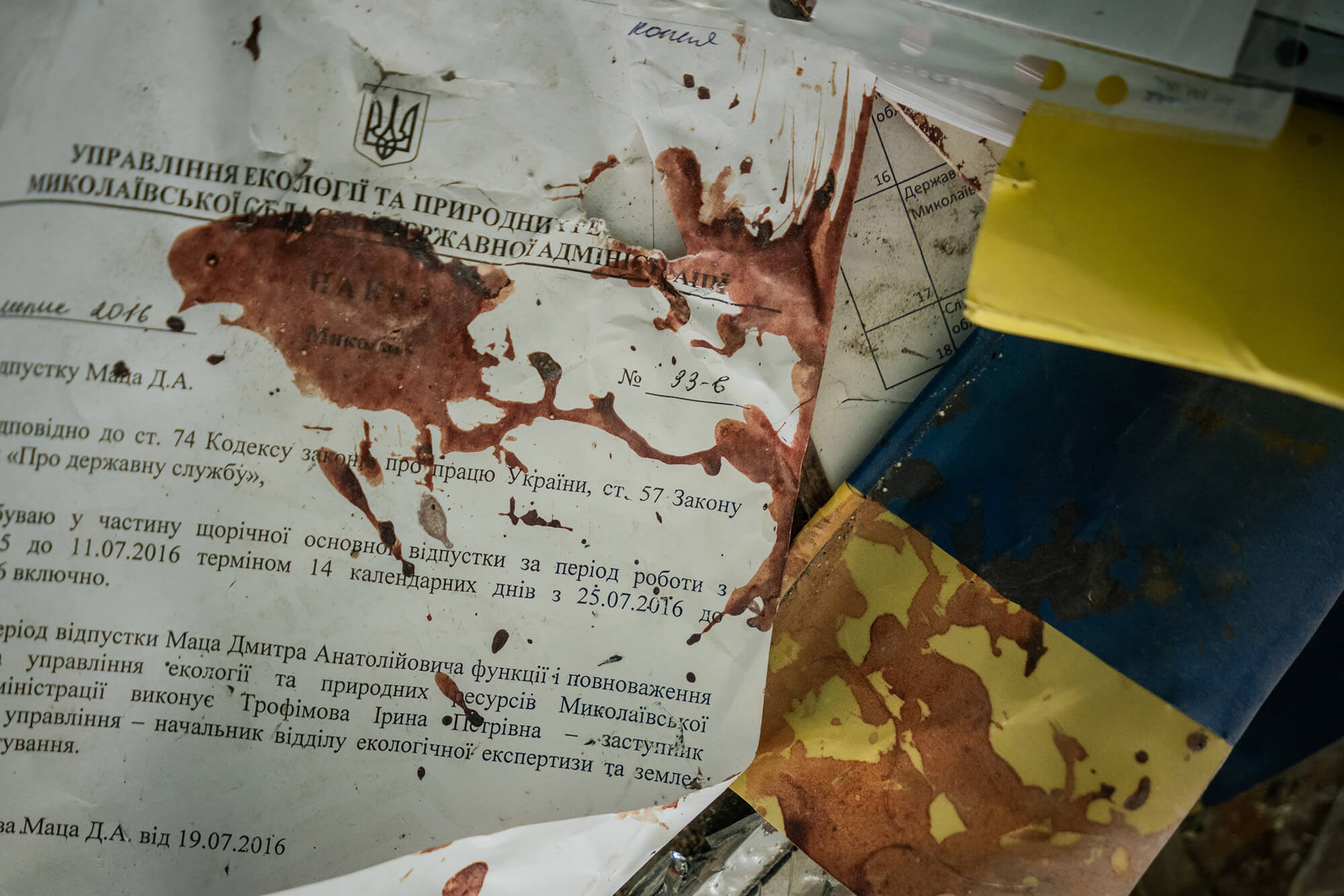

We are meeting Vitalii Kim near the building of the destroyed regional administration. Inside it, on each of the bombed out floors, lie the personal belongings of the employees. The floor is covered with a layer of fine glass that crunches underfoot. The security guard, who was inside the building at the time of the explosion and miraculously survived, is watering flowers. They were at the wrong end of an explosive wave, but the flowers, although withered, are still alive.

Every day, Vitalii Kim reports in his Telegram channel about Russian shelling in the city and region:

“The enemy has shelled the residential areas.”

“As a result of the explosion, several residential buildings were destroyed.”

“Due to the attack, storage facilities have caught fire.”

“Agricultural buildings have been hit.”

“The occupiers fired two missiles at one of our humanitarian headquarters.”

“Are they purposefully targeting civilian buildings?” I ask.

“Well, let’s say it is their parallel goal. Perhaps they are aiming somewhere there, but they fire missiles with an error from 600 meters to a kilometer. They are responsible for hitting the city center with such inaccurate missiles.

Out of the last 30 targets they fired at, only two were military,” Kim says, “all the rest were residential buildings in the sleeping areas.”

We are heading for one of them.

***

“They’ve recently started firing missiles that differ from the previous Smerch and Uragan multiple rocket launchers, which struck more with shrapnel,” says Ihor Rudenko, a rescuer with 22 years of experience. He and his colleagues are part of a team that is the first to respond to new strikes around the city.

We are standing in front of a building that the Russians have recently targeted. As in most cases, it is an ordinary residential building. When the shelling began, people were sleeping here, and eight of them were killed. The two upper floors were completely destroyed and are now just a pile of slabs and debris.

“We will start cleaning up from the top, as there is a risk that the building will collapse.”

The rescuer says that he is not afraid, despite the fact that two of his colleagues got trapped under slabs when removing debris and are currently in hospital with broken bones.

“At first, it was scary, but in the course of our work, we have overcome our fears. Someone has to do it, and we have the required skills.”

***

Russian rockets have also landed on the local zoo. It can only be considered a military target if you consider that eight workers joined the army to defend their land from the Russian invasion. Mykolaiv City Zoo is considered one of the best in Europe, with 211 rare species of mammals, birds and reptiles. Since the beginning of the war, eight missiles have struck the zoo.

The news about the shelled zoo caused a wave of support for it—people from all over Ukraine and abroad started buying virtual tickets. With these funds, the zoo’s management is able to buy food for the animals and keep on taking care of them. Despite the war, life goes on, and the local residents, including female lynxes, cheetahs and otters, have given birth to offspring since the war began. The funds raised from the sale of tickets were also used to drill a well when the city completely ran out of water.

Undrinkable water

It was cut off in mid-April. On the first day, the local authorities said not to worry, claiming that the water company Mykolaivvodokanal just needed to transfer the water supply pumps to the backup power supply lines. But the water never came back.

“They shouldn’t have said that,” Zinovii believes. “If we had been warned, we could have stored water supplies. However, no one was worried about it until it suddenly became clear that there would be no water for the foreseeable future.”

The Russians struck the water mains, which stretches for over 70 km from the Dnipro River—it was used to supply drinking water to Mykolaiv for decades. As long as most of the aqueduct is located in the occupied territory, it is impossible to repair it.

“We were lucky,” says Zenyk. “Water was trucked to us in tanks. There was a long line of around 50-70 people. So we worked together with the neighbors, took turns and carried water home in buckets.”

He says that people used any type of container they could find: three-liter glass jars, buckets, six-liter plastic bottles and even a few ten-liter ones, which Zenyk’s brother-in-law once used to make wine.

“There were occasions when we were standing in line for water and suddenly the air raid siren would sound. It was difficult to know what to do. If you hide, you will lose your place in the line. So we stayed and waited it out,” Iryna adds, dealing the cards for a new game.

The interviewees recall how happy they were when it started raining. They placed buckets under the gutter to collect water. Without it, you can’t even flush the toilet.

About a month later, the water supply resumed. It was taken from wells and the Southern Buh river. But you can’t drink it—it is salty and leaves stains on your hands. The residents of Mykolaiv have to buy water for drinking or cooking or get it from volunteer centers, where it is trucked in from Odessa and other cities.

Once every few days, Zenyk gets on his bicycle, which he usually uses to move around the city, and puts two six-liter bottles in specially equipped bags on each side. He puts another one in his backpack. This means he can bring home up to 30 liters of drinking water in one go.

“Now it’s a little easier. It was more difficult in winter,” he says and talks about how he started helping others.

Inevitable change

On one of the first days of the war, in the cold month of February, Zenyk’s wife got a call from a friend who had been helping the military for a long time. She said they needed people to heat up lunches in microwaves and deliver them to the checkpoints in the city center.

Following his wife, Zenyk also joined. For a long time, he was on night duty at a coffee shop in the city center (name withheld for security reasons), whose owner opened his doors to the military, turning the café into a headquarters of caring citizens. At night, when most of the volunteers were leaving to get some rest, Zenyk would start his shift. As soon as a soldier entered the café, he would make a hot drink for them—50-60 cups a night.

A bit later, he started giving out lunches prepared by the World Central Kitchen International Humanitarian Organization and distributed by a volunteer center. A dozen food distribution centers for displaced and elderly people, members of large families and anyone else in need of help were set up across the city. At the city center location, where Zenyk worked with his colleagues, hundreds of people would line up for two to three hours for the food truck, and when it arrived, 500 hot meals would be quickly handed out.

The work of the team that Zenyk joined quickly gained momentum. Today, the Soborna Volunteer Center, as the association is now called, is a large humanitarian headquarters. Volunteers search for and distribute goods for the army and victims of shelling. Aid arrives from across Ukraine and abroad: the USA, Israel, Poland, Portugal, Germany and other European countries. Volunteers are in contact with military units, and deliver additional food, equipment and medicines to Ukrainian fighters in remote areas of the city.

“We don’t give out lunches any more. But there is a lot of other work to do. . . My third cousin from the US sends walkie-talkies, water filters, flashlights, and first aid kit bags. Now my wife Ira works with volunteers in Kolomyia and they help with medicines, hygiene products and other such things. We do everything we can.”

There are many people like this in the city. Since 2014, Mykolaiv and its residents have changed a lot. These changes were gradual and often not obvious. First, the name of your native street was changed from Heroiv Stalinhrada to Heroiv Ukrainy. Later, military vehicles began to drive along this street. The city that for years stubbornly voted for pro-Russian politicians suddenly elected a pro-Ukrainian mayor, and re-elected him for a second term. Then your friends decided to take up the fight against the Russians, or took on volunteer roles, such as collecting ammunition for the troops or holding fairs discovering their volunteer talent to help others change the city for the better.

Resistance is in the blood

“Why then, in the 90s, did you decide to stay in the city? With your Lviv background, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, didn’t you feel like a stranger here?” I ask Zenyk.

“Quite the opposite,” he says, after a pause. “My parents repeatedly told me I should come back, but I could not imagine going back to Zhydachiv or Lviv. I had my work, my friends, and my hobbies here. I played football in a team on the weekends (and still do). Together we would go hiking in the mountains of Crimea, the Carpathians and the Caucasus. We went to the countryside to do rock-climbing, and had a training center that offered courses on mountain climbing. Later, I made it to the regional team. My whole world was here, they were my people, and this is where I laid my roots,” he shrugs his shoulders and smiles.

“Why didn’t you leave now? For the same reasons?”

“I think that people need me here. And as long as they need me here, I will stay.”

A bit later, he shows a message on his phone from a distant relative. After learning that Zenyk was staying in Mykolaiv during the war, she wrote enthusiastically that she was not surprised at all by his decision. And she told him that his family, as it turned out, were partisans in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army.

“It looks like resistance is a little bit in my blood,” you cannot tell from his smile whether he is joking or not.

“Uno!” Zenyk exclaims.

He has the last card in his hands. And he still stays here.

2.45: “Mykolaiv, air raid siren!”

2.45: “Missile hits!”

2.49: “Everyone, take cover! More hits!”

2.59: “Ten minutes of silence.”

You can support the Soborna Volunteer Center using the following details:

EGRPOU-44898982

UAH account: IBAN-UA633077700000026004011143064

USD account: IBAN-UA813077700000026003011143065

EUR account: IBAN-UA023077700000026002011143066

Bank card: 4323407004337365

PayPal: panas0863@gmail.com

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More