Permission to Live

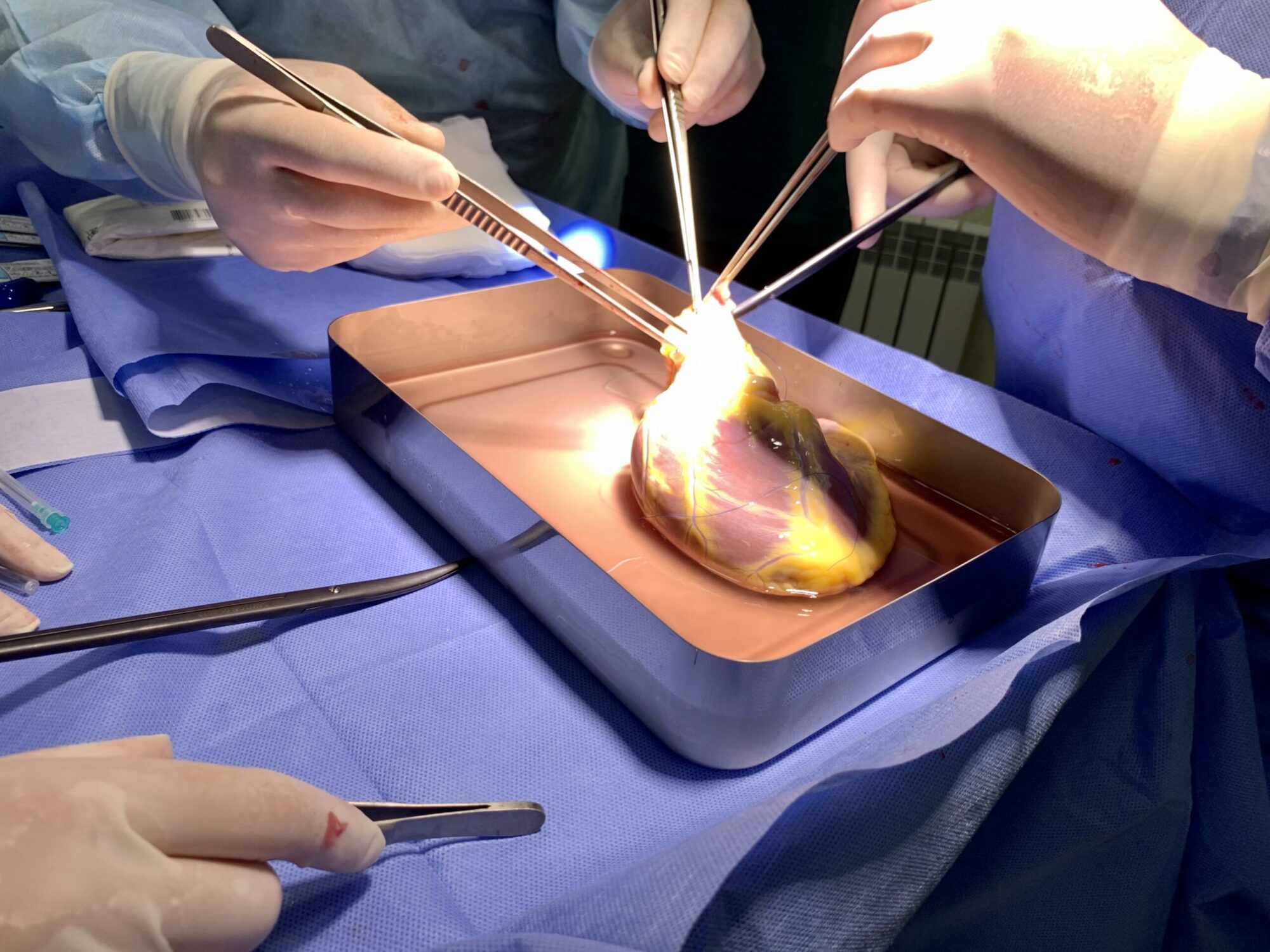

July 15, 2020. The Heart Institute of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine in Kyiv. Five surgeons wearing binoculars, masks and blood-stained gloves are leaning over the operating table. Another dozen healthcare professionals are assisting, learning from their more experienced colleagues. In the blinding light of the surgical lamp, the transfer of life is taking place.

A new heart held between the clamps and numerous tubes that supply blood and remove excess liquids has just started beating in the chest of a 64-year-old man. The patient’s own heart, three times the size of a regular human heart, lies next to him in a metal tray. Today, in this operating room, life has literally superseded death. The fourth heart transplant in Ukraine in the last six months has been made possible by a pilot project by the Ministry of Health that legalizes and regulates postmortem organ transplants. And the heart was donated by a young resident of Kyiv, who tragically passed away.

One Death and Four Lives

A narrow street leading to Lake Martyshiv is buried in the shade of gardens. Here, in this single-family residential neighborhood near the capital’s Slavutych metro station, everyone seems to know each other. The place feels like a small village. Meeting in the streets, the locals happily greet each other. And when they have time, they stop by the nearest store and discuss the news, sipping 3-in-1 coffee from cheap disposable paper hot cups.

Two months have passed since 20-year-old Maxim from the house by the lake was run over by a car when he was riding his scooter. Yet the locals are still discussing the tragedy.

“Because everyone here knew Max,” says a liquored up man whom I meеt first. “He just liked helping people, you know? He would mow grass, dig trenches. He was a great guy. I am so sorry for him. Such pity that it happened the way it did. . .”

“What way?” I ask. “You mean the accident?”

“Among other things. In general, I mean his father’s decision, for him to become a donor. They said on the news that the boy saved four lives. But I think that it was somehow wrong. And it looks suspicious, too: the accident on Tuesday seemed to be minor, and on Wednesday they said that he died. I also heard that maybe it was because of money: they asked for too much at the hospital, God forbid. . . Maybe they saw the father was a simple man and could not afford treatment, so they decided to do that. . . But I do not know for sure. What else is there to say, the kid is gone.”

Yet, those who knew Maxim all say he simply had no chance to survive. Immediately after the accident, the neighbors, whom the young man often helped to run some errands, raised one and a half thousand dollars for his treatment. And could have raised more, but the next day the doctors declared him brain dead and suggested the boy’s father to grant consent to donation.

“Max had a radiant personality. He was responsible and sincere, and always tried to help others.

I am sure if he could make the choice himself, he would have done the same as his father. Knowing the inevitable, he would undoubtedly have signed those documents as well.”

The owner of a local private kindergarten and a friend of the deceased young man is standing on the shore of the lake, squinting at the bright sun and straightening the hem of her long dress. She says that before the tragedy she never thought about organ donation, and now she wants to allow the posthumous transplantation of her own organs.

“I just need to sort some things out, and then I will do it,” she assures us. “People know nothing about it, no explanation is provided. So we have no idea that anyone can sign a consent for posthumous donation. If something happens and I can save someone’s life after my death, why wouldn’t I?”

Acquaintances say that despite his father and mother being alive, Maxim was brought up mostly on the streets. The boy did not explain why he studied at a boarding school and night school, and was only issued such essential documents as a birth certificate when he reached adulthood. He moved to Slavutych, to live with his grandmother and father, some five years ago. Since then, in the company of neighbors, he kept emphasizing that he wanted a better life for himself: to get at least some education, make some money, and finally see the seaside. The young man was only a few days from living his dream—he was due to go to Odessa on Friday, but died on Tuesday.

“Maxim’s heart has started beating in someone else’s chest. Having lost his own life, he has given it to four other people. How could that be a bad thing?” ponders a middle-aged man, also one of the locals, staring into space.

With a thick beard and long ponytail he reminds me of a musketeer. He befriended the young man, although he is old enough to be Max’s father. We are talking on the same road to Martyshiv, where on the eve of the accident Max told him how he wanted to create the best beach on the lake: to reinforce the shore, raise the level of the bottom, remove the roots under water, order a few trucks of golden sand, install some chinning bars and a playground.

Now, honoring Maxim’s memory, his friends plan to finish what he started. It is possible that the people whose lives he saved will someday visit the renovated beach in Martyshiv.

The Hearts of Other People

Until recently, surgery abroad was the only chance to survive for those who require a transplant from a posthumous donor. The hundreds of thousands of dollars needed for this could either be raised by patients on their own, or people could try their luck in a government program that pays for transplants outside the country. The way this program works was described by Reporters in an article entitled Shchygol: the story of a resident of Mykolaiv—a cancer survivor, who received a new heart in India, and recently underwent a kidney transplant, donated by her father.

The shifts in Ukrainian transplantology started in late 2019, when the Verkhovna Rada passed the Law On the Application of Transplantation of Anatomical Materials to Humans. According to the law, by the end of 2020, Ukraine planned to open 12 transplant centers in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odesa, Lviv, Dnipro, Kovel, Zaporizhzhia, and Cherkasy. The work of the institutions was to be regulated by the Unified State Organ and Tissue Transplantation Information System (EDIST), which would store the data of Ukrainians who during their lifetime decided to become posthumous donors. The system is still being tested, and its launch is scheduled for early 2021.

Thanks to the pilot transplantation project of the Ministry of Health launched as a result of this law, since the beginning of 2020, doctors have operated on more than two dozen Ukrainians. In particular, the hearts of other people are now beating in the chests of four of them. In addition to 12 centers, 14 more hospitals and medical institutions have joined the project. Ukrainians can now receive transplants from both family and posthumous donors in a total of 26 medical institutions, all paid for by the government.

Oleh Samchuk, Chief Physician at the Clinical Emergency Care Hospital in Lviv, even posted the cost of such operations on his Facebook page. The most expensive—a whole liver transplant from a posthumous donor or a partial liver transplant from a live family donor—costs the government UAH 929,125. The cheapest is a kidney transplant from a live donor—UAH 323,798. For comparison, in neighboring Belarus, such transplants would cost much more: liver—UAH 3.7 million, and kidney—UAH 1.6 million.

According to the all-Ukrainian platform iDonor, Ukraine spends almost UAH 700 million annually on the treatment of its citizens abroad. The pilot project of the Ministry of Health, which will be testing the Ukrainian transplant system until the end of 2021, allows doctors to save the lives of Ukrainians in their home country.

With the written consent of the relatives of the deceased donor, doctors have the right to transplant their organs without fear of criminal prosecution. Prior to the launch of the project, doctors who performed post-mortem transplants could be charged based on Article 149 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine—Human trafficking. In 2010, three doctors of the Shalimov National Institute of Surgery and Transplantology were accused of this criminal offence.

Yet, despite the legal regulation of post-mortem transplants, the lack of a single information system does not currently allow organs to be transported between regions. After all, it is the EDIST that will contain information about the location of donors and recipients, as well as the availability of organs and their possible transportation.

“So far, everything happens only through personal connections between doctors. They take the initiative and call each other. But this is what the EDIST is for,” Oleh Samchuk explains. “The system will clearly show the location of the recipient, the patients who will benefit the most from his or her transplant, and where it is best to perform the transplantation procedure. It will be clear where a transplantation can be faster and better, and where it will have the best implant survival rate. Currently, each hospital in the pilot project has its own “waiting list” (in Lviv alone, more than a hundred people are currently waiting for a heart transplant”—Auth.). And there should be a single “waiting list” for the whole country.”

According to Samchuk, despite having little experience in transplants, Ukrainian doctors have considerable potential in the field.

“All over the world, transplantation is a routine job,” the doctor emphasizes. “Ukraine does not lack professionals, it just needs a little push in the right direction. And also—the opportunity to study and train abroad. Transplantology must and will evolve, for one donor can save at least seven lives. After the death of the brain, paired organs are suitable for transplantation—kidneys and lungs, as well as the heart, the liver, the pancreas, the cornea, and even the uterus.”

Oh, Mother!

“Hello?! Hi! Can we come in?” one of the locals shouts while opening the metal gate.

Almost 10 years older, this neighbor was Max’s best friend. Together they were going to rebuild the shore of the Martyshiv lake, and before that—go to seaside.

At first, he would ask Max to help unload something or walk his dog while he was away on business trips. And later he trusted the young man enough to leave his own children with him. He says, “I knew the kid wouldn’t let me down.”

In a previous telephone conversation, the victim’s grandmother flatly refused to meet me. Now she allowed me in the yard only because Max’s friend brought me.

“How is it going? Do you have any eggs to sell? I will take a dozen. These are the journalists, by the way,” the man says out of the blue. “They came to ask about Max. It is hard for all of us, but people should know what kind of man he was.”

All her life Maxim’s grandmother worked at the Burevisnyk plant in Kyiv. After her retirement, the woman built another house in the yard: her son got divorced and needed his own home, and she also wanted to leave her grandson some inheritance. She did not take in Max right away, who was a few years old at the time, because she hoped that her daughter-in-law would come to her senses and quit drinking. When she realized that was no hope, her grandson was already a teenager.

“Honestly, I have no idea what to say to you. My son is not at home right now, but he worries a lot. He isn’t sure if he did the right thing. There was no time to think about it: doctors diagnosed the brain death, and to do the transplant on time, he had to decide immediately. I told him: “You did the right thing! Max would have died anyway, and this way he managed to save the lives of four people!” And he said: “Oh, Mother! What if I hastened his death? Maybe the doctors did not tell us, but in fact there was a chance he could have survived?”

The old woman cries, leaning on a chair in the middle of the yard. She requests that we refrain from taking photos: she is worried that the journalists will not leave her family alone.

“Worse, the relatives of those who are now alive thanks to Max would try to find us. It would be traumatic for us. It is hard for us mentally. My son did not sign the documents for money—no one gave us anything, and we do not need it. The only thing left for us is to come to terms with our tragedy.”

Bodies of a Fallen World

Although any transplant requires dozens of surgeons and a series of preliminary tests and examinations, and the donor organ must be transplanted within hours of collection, many Ukrainians still fear they may be killed “for their organs”. Many also do not understand that in order to prevent the rejection of a new organ, the recipient will have to take expensive immunosuppressive drugs for life, which can be obtained free of charge only under the government program—and only upon the official request of the doctor who referred the patient for the procedure. It is obvious that such a complex and highly-regulated process could not be carried out spontaneously in some “underground market”.

Religion also plays an important role in casting doubt and promoting myths about transplantology. For example, the Orthodox are worried about the promised resurrection. They say, when organs are taken, what kind of body will be resurrected—the whole body or the body buried without a heart, kidneys or something else? Archpriest, Abbot of St. Nicholas Church of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine in Poltava Oleksandr Dedyukhin says that donation is not contrary to resurrection.

“The Gospel teaches us that the bodies that people carry now are the bodies of the fallen world,” he says. “We will be resurrected in other bodies, corresponding to how well developed our soul is. In other words, the soul is a kind of a skeleton on which the body grows. From this point of view, I personally do not see any contradictions between posthumous donation and religion.”

However, the priest has his doubts about the presumption of consent, as well as situations where consent for posthumous donation is given by the relatives of the deceased.

“Even after the death of a person, the body is a temple of the Holy Spirit. That is why I have to share it with my own consent, consciously, and while I am still alive.

Meanwhile, the Vatican treats transplantation as a powerful expression of charity. Last year, Pope Francis said that donation is a testimony of love for our neighbor and a manifestation of social responsibility: “Even our death can become a source of hope for others.”

But there is not much hope for others in Ukraine yet. According to Health Minister Maxim Stepanov, nine Ukrainians die every day having not received a transplant. According to Dmytro Koval, ex-Deputy Minister of Health, more than 5,000 people are on the list for a transplant every year.

***

July 15, 2020. More than three dozen healthcare professionals representing several medical institutions in the capital met in the operating room at the Kyiv Emergency Care Hospital, where they are conducting a multi-organ harvest from a posthumous donor for the first time in 13 years. One of the doctors crushes an ice block with a special hammer. In an hour and a half, a 20-year-old heart, kidneys and liver, hermetically sealed in plastic and covered with ice, will be placed in a box labelled as “Human organ for transplant” and rushed to the Shalimov National Institute of Surgery and Transplantology. By tomorrow sunrise, the organs will be transplanted in four patients, who will be given the gift of life. This opportunity was granted to them by Max from the house by Lake Martyshiv in Slavutych.

Every adult Ukrainian can consent to a posthumous donation. To do this, you need to print and fill out the form on the official website of the Verkhovna Rada. And then sign it and pass it on to your family doctor.

[This story was created with support of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Norwegian government.]

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More