“I Remember Breaking Two Boiled Eggs Into 15 Pieces. Everyone Was So Happy.”

This story was created with the support of our readers.

She was born in Mariupol; he is from Volnovakha. She is 63; he is 62. They spent most of their lives together in Mariupol, where she was a teacher of literature and he worked on the railroad.

The war first reached them in 2014. Back then they learned what it was like to hear shots and explosions outside the window of your apartment. But the situation quickly stabilized, and their overwhelming desire to move to the western regions of Ukraine gradually faded. Instead, they became truly Ukrainian in Mariupol, a city that has impressed many locals with its rapid development over the recent years.

When the war came to Mariupol for the second time, they didn’t have time to even think about leaving. They left their hometown because it was their only chance to survive.

They refuse to give their names and be photographed. Both are afraid that looters would find out that they had left the city, identify their apartment and steal their valuables. They hesitantly talk about their plans to return home and go back to their apartment, where during the continuous airstrikes they would pray that their building would be spared. Their anonymity reflects their hope to return home, weak but still alive. Hope, nothing more. Neither of them is sure that their house has survived in a city that they say no longer exists.

They drove together in their car with her 84-year-old mother. Their eyes are full of anguish and exhaustion. We are talking in a relatively safe city in an apartment on the 9th floor, located near the airport. The previous tenants refused to live there, so they were “lucky” to get this place.

She is the only one of them to speak about the last weeks in Mariupol. Like everyone else who managed to flee the city, she remembers every day.

February 24

It was horrible. When I woke up, my husband said that a full-scale war had broken out in the country. “Please don’t worry,” he told her. As a person who lived all my life in Mariupol, I did not see any reason for this war.

March 1

The power got cut off in the evening. It turns out that when complete darkness envelops the city, it feels like you are floating in space. I’d never experienced anything like this before, because even when the power was cut off, some lights stayed on, even if only in the distance. Together with the city, we were plunged into darkness, and it was impossible to move around the apartment. We did not turn on the phones because we had to keep their batteries charged.

My 84-year-old mother was terrified, so the next day we decided to move to her place. We did not understand what was happening, and thought that they would fix everything soon. And we should just wait a bit.

March 2

We arrived at my mother’s place, washed our hands, and I started cooking. When I turned on the tap, there was no water. “That’s it. The water has been cut off too.” I immediately realized that the situation was serious. The shelling was very strong; it was obvious that the water wouldn’t be back on any time soon. The roar of explosions deafened the entire city.

March 3

We tried to buy medicine, but the pharmacies were already boarded up. The windows of grocery stores were smashed; people took everything they could, in big bags or just in their hands. Eventually, people were taking everything; they were running through the streets, carrying clothes with labels hanging from them.

March 4

The shelling grew stronger. A shell hit the corner of our house. This really affected me. The house moved under the force of the impact; the wooden-framed windows shattered. At the time, we thought we were seeing the worst of it, but later we learned what real terror is.

We would sit in the corridor on three stools. The more intense the shelling, the more crowded the basement got. But we tried to go down, with my old mother who is 84 years old. We dragged her along. She was patient and managed it, walking very slowly.

March 5

We noticed that the traffic on the main avenue was busy, which had not been the case for several days. We went out into the yard and saw people loading suitcases into their cars. We asked one of the drivers what was going on. And for the first time, the word “evacuation” was uttered. He told us that there would be a green corridor at 11.00 near the stadium.

In a mad rush, my mother and I packed our bags as my husband hurried to the garage to get our car. When we arrived at the stadium, there was already a long line of cars. There were even people who had come on foot with backpacks. People were not sure what was going on, asking each other questions until a Ukrainian soldier approached us and said that there would be no green corridor. They advised us to return home where it would be safer.

It was a huge letdown; we had hoped to the last that we would be able to escape. We left our car in the garage and walked home. On the way, we saw a dead man on the road for the first time; his face was covered with a rag (he was still lying there five days later). There was a shell hole nearby.

“What’s that?” I asked my husband.

“A dead man,” he replied.

We walked on. I felt nothing, only numbness. Perhaps it was my mind in self-preservation mode.

As it turned out, there were many bodies on the streets and under the rubble. The emergency services could not keep up with them.

March 6

The gas was cut off. We were very scared, as a cold front had struck.

People went outside to light fires in pits made of bricks or cinder blocks. Each entrance in our apartment block had its own fireplace.

At first, we felt uplifted as everyone was united; an acquaintance even said, “Imagine that we are on a communal picnic, that it’s Easter now.” We started cooking together; someone brought out a bottle of cognac. “Let’s take a picture,” someone suggested. We were really pretending that we were on a picnic.

This mood lasted for two days. Then came the realization that there would not be enough firewood for everyone, and some people began to hide their wood. We no longer lit common fires; everyone just came in turn with their pile of firewood.

People cut down trees in the yard, but they were wet, producing only smoke instead of burning. People started looking for boards in the basements, then started burning their furniture. Some even took out baby cribs and burned the colorful wooden fences of the kindergartens. Our grandmother suggested tearing off door frames and burning them.

We continued to wear pajamas, warm fleece robes, jackets, scarves and hats, which we did not take off once in the following days.

March 7

We lived in an area that was subject to the most intense shelling. Isolated, without any means of communication, we could not go far from our home and made our food last as long as we could. We did not know how long the situation would last.

We had no food stocks to speak of. First, we cooked the frozen food before it spoiled. We also had groats that we used to cook thick soups. We avoided the canned fish, because it would make us thirsty. There was no bread, but my mother liked dry bread so we had a packet of rusks. My mother asked us to save the potatoes because we might not have a chance to get any more until next autumn. We were so anxious that we had no appetite and gradually lost weight, although we did not realize it at the time.

Ukrainian photographers document Russia’s crimes and the heroism of Ukrainians so that the world can see the truth

March 8

There was a flower shop nearby, which had not yet been looted. We went out to the fire, and the men were carrying bundles of roses and chrysanthemums. Men gave flowers to the women in their basements.

The driver found a shell in a car parked under our balcony. I used to think that shell fragments were small things, like a tiny pebble, but that’s not true. This fragment was half a meter long, sharp on all sides. This, of course, had a big impact on me.

Usually not very sociable, I rushed to people asking whom they had managed to call and how. People directed me to a small area where there was a phone signal. On the way, I noticed that all the shop windows were now broken, and the street was littered with Christmas-tree decorations. Nearby I saw a crowd with phones; they were huddled together on a small patch of land, calling their loved ones.

I called my son abroad and asked if the world knew what was happening here.

“Do you realize that we’re going to die here?” I shouted into the phone.

“Yes, Mum, the whole world is talking about Mariupol,” I heard in response.

“But is anyone doing anything?”

March 9

The first bomb, I believe, was dropped on civilians that day. I remember the moment well. I was sitting next to a partly closed window. The explosion forced it wide open, the plaster scattering inside like fireworks. The house shook like it weighed nothing, and we shook with it. The bomb fell 500 meters from our house.

Until then, we used to believe that they were trying to hit only Ukrainian military targets. But no, they dropped that bomb on civilians. I truly believed that they would leave ordinary people alone.

March 10

Bombers began to fly after dark. My husband did not sleep all night. One plane dropped two bombs. Then it flew away. After a while, another would fly over. With a huge roar. Two explosions and it flew away. Later, they no longer arrived one by one; but in groups. And in between the sorties, Grad MRLs and mortars were fired at us. We ignored the explosions and continued to cook food on the fire, only hiding when the bombers appeared. Around the fire we talked about what was happening. Dejectedly we talked about the sorties, that there had been no bombings for two whole hours or that the night had been relatively quiet.

They usually started bombing in the morning between four and six a.m. We waited out the bombings in the hallway of our apartment, telling ourselves it was safe there, and just kept quiet, clenching our teeth. We waited for it to end.

A few hours later, we went to the fire to quickly cook our food. During the day, the bombings did not stop until 7-8 p.m., in time for dinner. Then it started all over again.

It felt like we had been abandoned and nobody cared about us.

March 11-12

The bombings were relentless. The house shook all night, the floor moved beneath us. At such times, you can’t think about anything. For the first time, I was terror-stricken; my heart was jumping out of my chest. The fear turned into foreboding. You’re just waiting for it all to end.

My husband insisted that we run down to the basement. I told him, “Let them get us, and this will be over.” It was impossible to endure it any longer. No water. No gas. No power. No way to talk to the outside world.

It was freezing, with subzero temperatures, and we couldn’t keep warm. When I was a child watching movies about the siege of Leningrad, I could not understand why they filmed people who were constantly lying down in these cold apartments. Now we also lay down to save energy. It was difficult to sit up, and lying down saves you energy and strength. We lay in our hats and jackets wrapped in blankets, as in besieged Leningrad. “At least they handed out bread in Leningrad,” my mother said.

People did not leave their basements at all. Just to boil the water they got by melting snow. It turns out that you can’t get much water from snow. Melt a bucketful of snow and you get so little water. When the snow later melted and it rained, people drew water from puddles.

We were a little more fortunate. Before the water was cut off, my mother drew a full bath. Before, I used to scold her for doing it, asking how she was going to take a shower. But now this was the water we had. We limited it, and made it last as long as possible.

We drank so little water that we only went to the toilet once a day. We had to pretend that the toilet was a hole in the village outhouse. That there was simply no drainage tank, nothing. People used to live like that, right? We didn’t wash the dishes, although I would try to wipe them with a napkin. It was so cold that bacteria couldn’t survive anyway.

I couldn’t sleep at night; I kept thinking what we would do if the water ran out. That would mean death.

There was no space for us in the basement.

March 13

Explosions. Endless shooting. It felt like living on a shooting range. We learned to distinguish shots from hits.

I remember when Putin threatened the big red button at the beginning of the war, but it was still relatively quiet in Mariupol, and we would say, “Go ahead, press the button. We will not give up.” Now we just want it to end as soon as possible. Why are we being killed?

Our acquaintances previously found shelter in the suburbs by the sea. We didn’t know if they were still there. We decided to take the risk and go and see. Me, my husband and my old mother. We took nothing with us except blankets. We were lucky, as our acquaintances were still there. It turned out that several families lived there. Some of them previously lived on the outskirts of the city but no longer had a home. They took us in.

March 14

In total, there were 13 adults and two children.

We had a routine: morning tea; hot soup made of water and pasta for lunch, perhaps with a piece of cabbage or some ketchup thrown in. We had some potatoes, but we didn’t peel them, because you can also eat the skins.

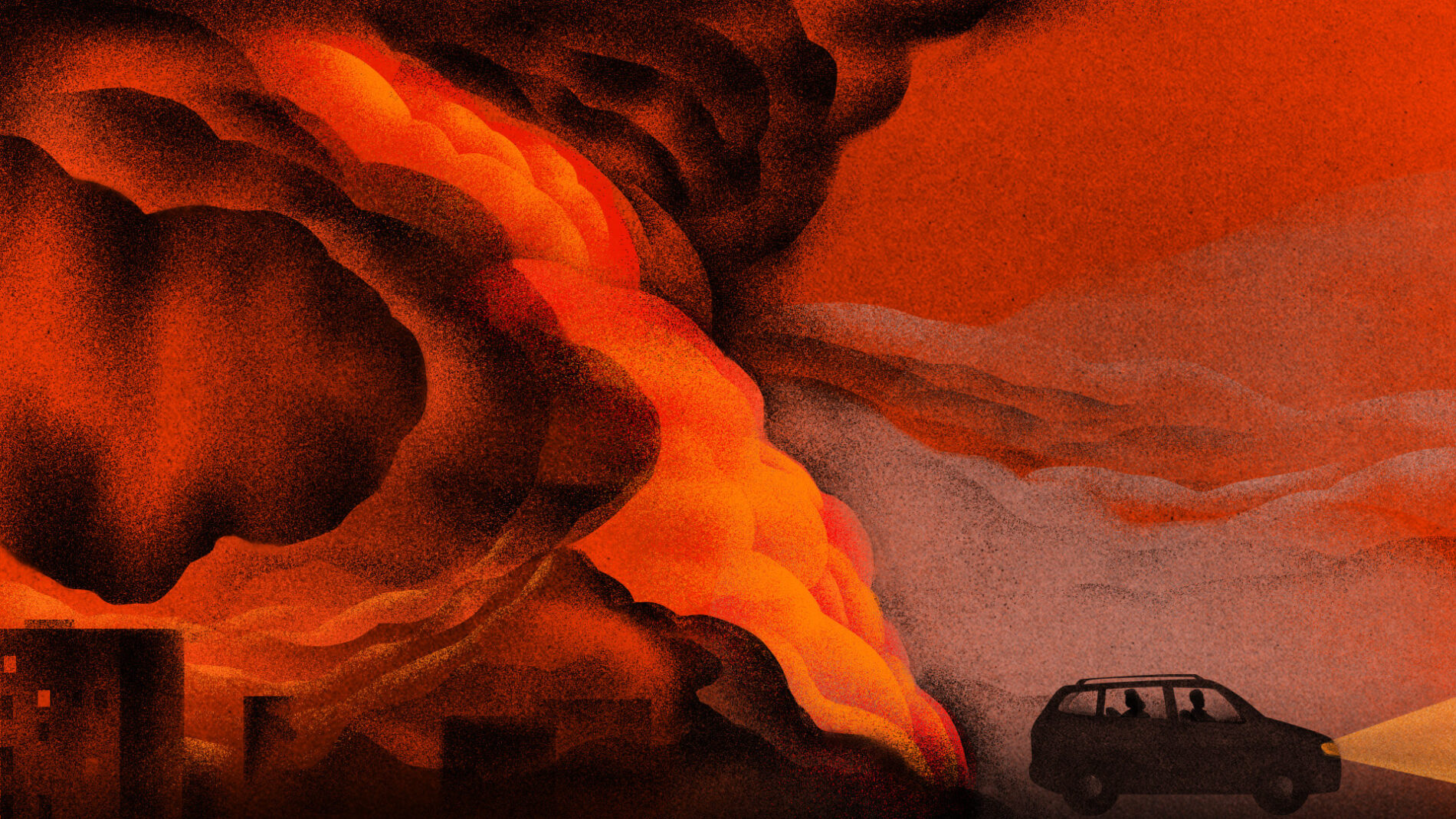

We had a clear view of the city, and at first, it was “safer.” We heard explosions and saw smoke rising over the affected part of the city. But we had a sense of safety because we were “far away” from it all.

Bombs. Shelling. Explosions. This sound of the explosions, though remote, was constantly echoing in my mind.

March 15

The house began to shake. We went out in the morning and saw that the whole city was engulfed in fire and smoke. They were bombing it without remorse; there were numerous jets, circling over the city like birds of prey.

I called my son and said goodbye to him. It felt like it was over. The blaze was getting closer; the city became just smoke. What was there left to do? Jump into the sea? There were Russian ships there as well.

“Don’t worry, I have lived a good life. It is what it is,” I told my son on the phone.

I was sure that there was no way out. We were encircled; the bombing was so heavy that there was only one thought on my mind, “We’ll be hit any moment now.” It seemed to be only a matter of time.

Instead, my son persuaded us to leave, insisting that we try. We made our way towards Melekine. It turned out that there were thousands of cars under constant fire. However, no one reacted to it; everyone just wanted to leave. In two hours, our car did not move an inch. We returned “home.”

March 16

We woke up at five in the morning. There was a taxi driver among us; he offered to try again on a different road. We drove down side roads.

And succeeded in escaping the devastated city. I don’t know what’s left of it.

We escaped to Mangush; there were Russian tanks with the letter Z there. The first checkpoint was near Berdyansk. The Russian military took all our details.

We had a limited amount of petrol, so we were very afraid there wouldn’t be enough to reach Zaporizhia. There were four cars for us all, and we shared the petrol we had. We also picked up two old ladies on the way and fed them. I remember breaking two boiled eggs into 15 pieces. Everyone was so happy; it was a real treat for us.

The next town was Tokmak. There were two checkpoints in each small village we passed: at the entrance and the exit. We didn’t know who was manning them. They wore military uniforms with white armbands or legbands. The only thing we knew for sure was that we passed through occupied villages.

We were lucky, but we heard that people were robbed at checkpoints; that their money and phones were taken away.

When we were approaching Zaporizhia, our convoy was brought to a halt. They said that a hundred cars would be let through at a time. We waited in the queue for a long time. And they, the ones with the white armbands, hit us with mortars. They let us through, but when some cars reached the top of a hill (we were among them), they started firing. The rounds exploded 200 meters away from us. Five people were injured, one child seriously.

All the cars instantly hit the gas, jostling with each other to get away as fast as possible.

We entered Zaporizhia, shaking with fear. The journey, which in peacetime would take less than three and a half hours, took us 13 hours. We were terrified, but it wasn’t courage that helped us; rather the fact that we drove together in a convoy of four cars. We probably wouldn’t risk taking that road on our own. Together, it was not as scary to drive when under fire.

When we were met by volunteers, we felt safe. These were our people. It was so wonderful feeling their care. Nobody told us off for being in the wrong queue during registration; everyone treated us politely and with kindness, even offering us food and accommodation. This, however, was not a problem for us as we were on our way to our friends in Dnipro. The compassion of these people meant everything to us.

March 17

We reached Dnipro and finally undressed, for the first time since March 1. It was such a weird experience not to wash or undress for so many days. Not to mention the need to save water and food.

In Zaporizhia and Dnipro, we saw sandbags, metal “hedgehogs” and anti-tank ravines. Now I know that none of this matters when planes drop bombs.

Mariupol is on my mind. No one could have imagined that in the 21st century, an army would purposefully exterminate an entire city, district by district.

After 2014, Mariupol began to develop rapidly. This is the city where we became truly Ukrainian. Until 2014, we had no special feelings for Ukraine; we just lived our lives, lives that were closely intertwined with the Russians. They often came to Mariupol in the summer, while many of our relatives lived in Russia. No one talked about these things. After 2014, we fell in love with the Ukrainian language; we did not support the annexation of Crimea or the occupation of Donbas. The freedom and independence of our country are important to us. We saw no reasons for the attack on Mariupol.

March 19

We arrived in Lviv. For now, we want to stay here.

We do not feel lucky. I live with constant anxiety because I do not feel safe. In Lviv, they say the same thing we said in Mariupol, “This cannot happen, they won’t attack us here, we are protected.” We used to say the same thing.

I feel the constant need to run away. Where to? I do not know.

March 20

Today is my mum’s birthday. She was born in 1938.

Even before the bombings began in Mariupol, we knew we needed to save all the candles we had. We would spend the evenings listening to my mother’s stories. In the dark, to the sound of Russian shelling, she told us how she survived World War II as a child and what life was like after the war.

“My life began and will end in war,” she concluded in the dark.

We don’t know and can’t even imagine how many people died in Mariupol. At first, the police would drive around the city and collect the bodies. But then they stopped as the shelling was too heavy. Buildings are still being destroyed. People are trapped under the rubble. There is nobody to rescue them. The death toll is much higher than we hear in the media.

Many people prayed for us, but we just got lucky.

March 23

Recently, after we had already left Mariupol, a very close friend from the Russian city of Saratov called me and asked, “Don’t you want to be liberated?!”

So now we are “liberated.” We have nothing. We were “liberated” from our jobs, our city and even our past. At the age of 63, we are now forced to start our lives from scratch.

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More