Crucified

She has a house like thousands of others in Polissia. Whitewashed with clay, with blue windows. There is a well nearby. The barns are barely holding together amidst the frost-cracked apple trees. But it was this house in the small village of Sokil in Volyn that became almost a place of pilgrimage for Polish historians, diplomats and reporters who investigated the events of 1943, calling them the Volyn Massacre and nothing else.

Baba Shura and her 12 cats live here.

A few years ago, the world learned about the existence of Baba Shura. Oleksandra Vaseiko from Sokil became the heroine of the book Machine Guns and Cherries by Polish reporter Witold Szabłowski. The author told stories “about good neighbors from Volyn”—the Ukrainians who saved Poles from death during the punitive actions of the UIA [the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, the Ukrainian nationalist political and military organization engaged in guerrilla warfare against Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union for an independent and unified Ukrainian state—R.] in 1943.

Some people in Poland did not welcome the intention to depict Ukrainians as merciful. Yet, last year Baba Shura went to Warsaw, where she received an award from President Andrzej Duda. Now she keeps the award in an intimate place of her house—atop the wardrobe, along with Szabłowski’s books.

But this is a story of the life of heroes despite books about heroes.

***

There is a table in the holiest room of her house. And that table is like an altar.

In the center, there is a photo of Baba Shura standing next to President Duda in Warsaw. Next to it, there is a photo with Szabłowski. Then there are numerous icons. . . and a dusty portrait of the presidential couple. Wearing a snow-white jacket, Lady Duda looks at an old bed with a metal headboard and smiles proudly.

At the corner of the table, there is a flag with the symbols of the Polish Volyn Motocross Club. The flag is red and white, and the table is covered with an oilcloth, blue with yellow sunflowers.

Baba Shura picks up a small radio from the table and tunes it in dashingly.

“I have no TV, so I make do with the radio. My daughter brought it and said: ‘Here you go, mom, because you like listening in Polish.’ So I listen to it when there is time,” she puts the radio back.

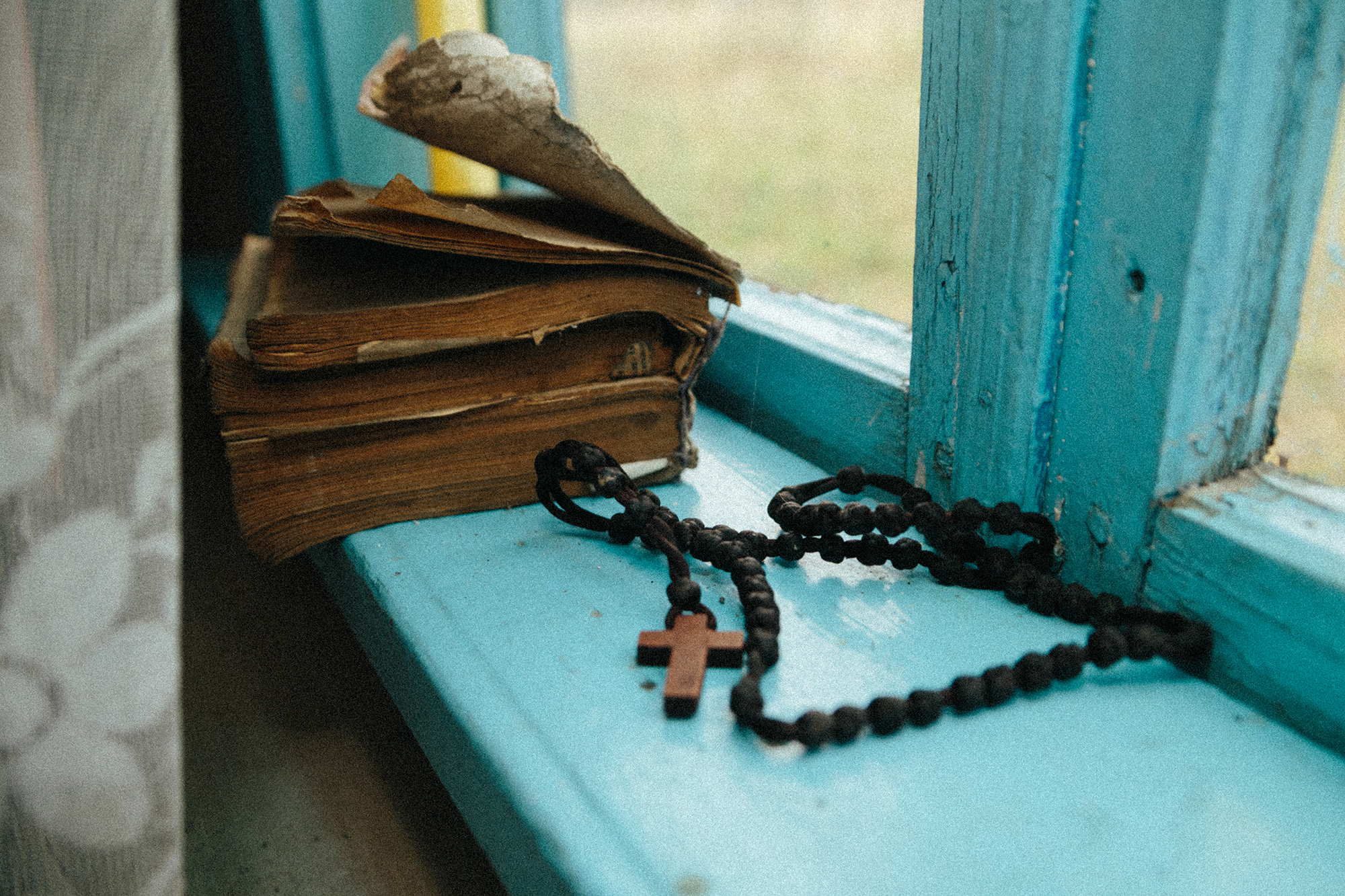

There is a Gospel lying on the windowsill, behind the curtain, and it is black as coal—either from old age or from such a life. Through the window you can see an old orchard, a bit of the garden and some countryside. Baba Shura prays under this window.

She listens to the news in Polish and prays in Ukrainian.

Immediately next to her Sokil is the Trupy tract. This is the former Volyn village of Wola Ostrowiecka, vanished after an attack by the UIA on the last night of August 1943. The vast majority of its inhabitants were Poles. Baba Shura goes to Trupy to pick berries and clean the burial places of the Poles killed that night.

Her family lived in Volyn from time immemorial. She knows as much about history as a regular village woman can, all her life—a milkmaid on a collective farm. She tends the graves because her father entrusted them to her. She uses Poles as an example for Ukrainians, for they care about their history.

Some of her neighbors look askance at Baba Shura. But in her mercy, Baba Shura ranks above all historical debates.

Crosses

The fields around Sokil are full of crosses. It is a small settlement next to the border. Just a handful of houses among the woods, a stone’s throw from Poland.

Today Sokil must be the closest village to Wola Ostrowiecka and Ostrówki. Destroyed in 1943, at the time they were the areas of compact Polish settlement in Volyn. History has made them one of the epicenters of the Ukrainian-Polish conflicts. In the summer of 1943, Ukrainian insurgents carried out a series of campaigns aimed at cleansing the region of Poles and liberating Ukrainian lands for Ukrainians.

On the night of August 30, 1943, these villages were attacked by detachments of the UIA. Women and children from Ostrówki were rounded up in the church. Men were locked up at the school, and later were taken to remote backyards and shot. In Wola Ostrowiecka, villagers were killed where they were caught, and only a few managed to escape. The bodies of those killed lay in the open for several days, until the insurgents finally ordered people from neighboring villages to bury the corpses. Dreadful stories about this event are still told here.

The Soviets did not rebuild the villages. They did what they always did—plowed the land to use it as fields. For decades, until the collapse of the Soviet Union, these lands housed the remains of hundreds of people, and local villagers secretly passed on the memories of horrific murders.

For Poles and Ukrainians, these sites in Volyn are places of remembrance of the 1943 tragedy. For Baba Shura and her fellow countrymen, they are places that “tell the tale” of the fate of their neighbors. What really happened in August 1943, Sokil people still cannot explain with certainty. Nor can they name the perpetrators.

The conflicts between Ukrainians and Poles did not come as a surprise. They had been coming for a long time. It all began long before 1939, when Ukrainian Volynians happily welcomed the new Soviet government, not yet realizing that one invader was simply giving way to another. They greeted Soviet soldiers with flowers when they entered the villages of Volyn. Why?

Since the early 1920s, when Halychyna and Volyn finally came under Polish rule after the Peace of Riga, neither Galicians nor Volynians felt like they were the masters of their own land. Having given a little freedom to “Prosvita,” the Ukrainian language and culture in the 1920s, Poland curtailed this pro-Ukrainian policy in the 1930s. In the villages of Volyn there were only Polish schools, where the teachers were mostly Poles. Polish Roman Catholic churches were built here. Volyn land was distributed en masse to Polish “settlers,” veterans of Józef Piłsudski’s army. But the Ukrainian peasants were stinted in land titles. And even the foresters (“gajowi”) in the region at that time were mostly Poles.

There was a growing “social gap” between Poles and Ukrainians. Volyn was dotted with “lordly estates.” Polish magnates had entire villages in their possession until 1939. Ukrainians worked on these “folwarks” as workers, with significantly worse wages and no opportunities to improve them. Yet, they tried to live peacefully alongside their Polish neighbors. To this day, their descendants tell stories about how they worked side by side, made friends and even married each other.

With the arrival of the Soviets, the Polish government emigrated to London, where it worked in exile. Yet, it never gave up its “Volyn ambitions:” it continued to regard Volyn as Polish land, forming and deploying units of the Armia Krajowa, which were to maintain control over these territories. At the same time, the UIA was actively working underground here, fighting for the right of Ukrainians to independence on their land. Thus both sides became enemies.

As of the spring of 1943, local Poles increasingly turned to the German police. The Germans involved them in attacks on a number of Volyn villages. In May, the German invaders used the Polish police to destroy the Volyn village of Krasny Sad. In June, mass killings of Ukrainians took place in villages around Lutsk—punitive actions involving Polish police in Cherchytsy, Krasne, Maly Omelianyk, Zmiyinka. Both women and children were killed and churches were destroyed.

And then in July and August, the UIA units attacked the Polish villages of Volyn. Volynians remember the horror of those events to this day.

People are living between the truths and the wrongs of 1943. On both sides of the Bug, they are still debating whether it was a tragedy or a massacre.

Baba Shura from Sokil simply says: a calamity for which we now must pray.

Eagles

Volodymyr Kryzhuk comes from the neighboring village of Rivne and has known the area since childhood. A former village head, he takes us to Baba Shura. We drive along the road between two fields. For us those are just fields. He says that, before 1943, Ostrówki was here—the largest Polish village in the neighborhood.

A common past for both countries, where they still cannot meet to stand side by side on the edge of the same grave and pray for the repose of the souls lost, made this primary school teacher (and later a bailiff)—a guide, a diplomat, and even an amateur historian.

He takes us to the place where a large wooden church stood in Ostrówki until the night of August 1943. We walk on green turnips: they still sow and harvest here.

“Do you see the white spot in the field? That is the sculpture of Our Lady of Częstochowa. The Poles consider this “Matka Boska” a symbol of their state.

This small sculpture of Matka Boska Częstochowska was dug out by a collective farm tractor driver in the 1980s. The earth gave the people what was left of the destroyed church. The peasants placed it in the grass under the lilac in the middle of the field.

In 1990, Poles came here for the first time and erected a monument on the site of the church.

“When they dug out the Mother of God, they saw that she had no arms or face. So they decided to restore the sculpture. I witnessed it with my own eyes: in a year the arms fell off, and so did the face. It became exactly as it was when they brought it up from the ground. And I believe it happened for a reason,” Volodymyr says.

A flag with an eagle is tangled in a branch above Matka Boska. Opposite, there is a black plowed field with another cross. There was a well here, from where sometime in 1992 the first bodies of the killed inhabitants of the village of Ostrówki were brought to the surface.

“In fact, Poles dream of buying all these lands. They are obsessed with it. If it were possible, they would buy them instantly,” Kryzhuk sighs, shaking the raw earth and the remains of turnips from his shoes.

For almost three decades, these Volyn lands have been the center of talks on forgiveness and reconciliation. Exhumation works were carried out twice in Ostrówki and Wola Ostrowiecka: in 1992 and 2011-2012. These events are evidenced by a memorial halfway to Sokil, in a magnificent pine forest. As soon as Ukraine became independent, in June 1992 the Luboml District Council allowed the Lublin Society of Friends of Kremenets and the Volyn-Podilia Land to carry out exhumation works and commemorations in the two villages destroyed in August 1943. The Society is headed by Leon Popek, a historian, archivist and, at the time, research professor at the Lublin branch of the Institute of National Memory of Poland. For him, it is also a personal story. His mother Helena comes from Ostrówki.

In return, in 1992, Poland declared its readiness to open a memorial site in Sahryń, a Ukrainian village in the Kholm region, which was burned in the spring of 1944 by soldiers of the Armia Krajowa, killing more than eight hundred Ukrainians. It was also agreed to continue work on the restoration of the Ukrainian cemeteries in Gmina Mircze, which fell into decay after the forced deportation of the local Ukrainians in the 1940s.

In 2011, they started cleaning and tidying up the old cemetery, which was once common to Ostrówki and Wola Ostrowiecka. Preparations began for the creation of a joint memorial, which was planned to be unveiled with the participation of two presidents—Bronisław Komorowski and Viktor Yanukovych.

Burials were restored at the expense of the Polish state. The fence, the road and assistance with general construction work were provided by the Ukrainians. Yet, the presidents never opened the memorial.

In the center of the cemetery, just behind the gate, there is a granite cross. On either side of it are two large areas sown with grass: common graves with remains. On one side—those found in 1992, on the other—in 2011-2012.

“Unfortunately, it is still not finished. There were to be two more crosses and eight nameplates. The Poles wanted to mention up to 1,500 names of people who died at the hands of Ukrainians. Ukrainian historians say this figure is exaggerated by several hundred people. In total, there are about 800 people in these two mass graves,” Volodymyr Kryzhuk explains.

If one stands in front of the central memorial and raises their head, they will see an empty space from a sign at the top of the granite cross.

“There was an eagle there. The scandal roared across Poland. The memorial was made by a Lviv company. But the Poles did not pay them for something. So employees of the company came and removed the coat of arms. Then the Poles started writing that the Ukrainians had insulted the Polish cemetery. Later, however, there was a refutation. . . Yet the Lviv company never returned the eagle to its place, he says.

A large delegation of Poles comes here every August. From May they come to clean and weed the area, and live in tents nearby. In recent years, the events at the cemetery have commemorated not only Poles who died at the hands of Ukrainians, but also Ukrainians who died just as innocently at the hands of Poles in Volyn.

The candles never go out here. The place is quiet. Уou can almost hear the moss creaking on the sand. There are white and red ribbons, but no blue and yellow ones.

A Holy Woman

In 2016, the Polish reporter Witold Szabłowski published a book of travels through the villages of Volyn entitled Righteous Traitors. Neighbors from Volyn (in Ukrainian—Machine Guns and Cherries). He was asked how he, a Pole, managed to gather evidence from Ukrainians. After all, they talk about how Ukrainians committed crimes against Poles in 1943. The author replied: “I was lucky. First of all, I met a holy woman.”

The “holy woman” still lives in the Volyn village of Sokil, 30 kilometers from the border with Poland.

She is thin. Her hair is grey. Although weak, she is still active. She tirelessly tends the graves in the local forests. Brings the first snowdrops to them.

It was Baba Shura who once showed Leon Popek several graves in the forest where people from Wola Ostrowiecka were buried. She warmly calls the Polish historian “Lion” or “Livon” as they say in Polissia.

Some neighbors claim that Baba Shura benefits from her friendship with Poles. She knows it. And laughs in response.

During 20 years of friendship with the Poles, she has not received any special benefits for herself, except for sweets and other such treats. Yet, last winter a whole Polish delegation headed by the Secretary of State Adam Kwiatkowski and the Consul General of the Republic of Poland in Lutsk Wiesław Mazur came to Oleksandra Vaseiko and brought her. . . a washing machine. Baba Shura gave the washing machine to her daughter and is very happy that she could help in her old age.

Volodymyr Kryzhuk says: it is not that Baba Shura gave her life to tending the surrounding graves. Yes, she really did show one of the graves and told the story of her father, the Ukrainian Kalenyk.

“It is just that her story is very important to Poles. And sincere and friendly to all, without exception, Baba Shura has gained the image of a kind of Polish folk heroine in the Volyn land,” he thinks.

She perceives stories of reconciliation, forgiveness, tragedy and massacre in her own way. She says Poles know how to pay respects, but Ukrainians do not. And without Poles, Ukrainians are no good for anything. She says that the graves would not have been restored without them, and half of Ukraine makes its living from working in Poland.

It didn’t take me long to persuade her to talk. She clapped her hands. Shooed her cats away. And went looking for a new kerchief.

Baba Shura hosts reporters as if they are relatives visiting for a special celebration. However, mostly Polish people come to see her. When we found her she was busy with her cow in the barn, the only animal the woman has except her cats. The villagers joke: Baba Shura keeps a cow so that the cats have milk.

“I buy lard, I don’t keep pigs any more. The villagers joke that I got a cow to feed my cats. No, it’s for myself, and for the children.”

In the corner of the room there are three 3-liter jars of milk in buckets of water.

“I used to walk to Polapy for bread. And now they bring us bread twice a week, so I get five or six loaves. Everyone asks me: ‘Why do you need so much? You live on your own!’ And I say that I need to put on some weight. But I don’t tell them that I have so many cats, they need a loaf of bread a day!”

On the table in her cramped house, there is an iconostasis of photographs of the Polish president, historians, and researchers. Among numerous bags, old photos and documents, Oleksandra Vaseiko has been looking for another photo for a long time, because she really wants to show it to us.

“Here it is!” she takes it out happily. “Witold said that it was a very nice picture. Nobody has anything like that.”

It is a selfie with Andrzej Duda. Last year he presented Baba Shura from Volyn with the Virtus et Fraternitas medal. This is how Poland commemorates those who saved Poles during the war and under the rule of totalitarian regimes. The bags contain the entire photo biography of Baba Shura and her Ukrainian-Polish mission: photos of her tending the graves, with Polish journalists, of a trip to Warsaw, where she is standing on stage wearing a festive headscarf.

“Witold was worried that I would say something I shouldn’t. And I said: ‘You know what? There is no need to worry! Everything will be fine!’ He asked whether I was afraid of their president. I said I was not. I am not afraid of presidents. I’m afraid of mosquitoes and thunder, nothing else!” she laughs.

One of the especially valuable artifacts owned by the old lady is a worn-out letter, although it is not so old.

“Hello, Baba Shura!” it goes. Evelina and Daniel, journalists from Poznan, wrote to her in Russian to thank her for the warmth, jokes, and scrambled eggs with lard they were treated to here for the first time. That’s why their photos have also found their place on the lady’s “altar.”

She does not hide the fact that she is considered eccentric by other villagers, both because of her special friendship with the Poles, and because she “makes much of the graves”.

“I pray near those crosses, and clean the graves. As soon as snowdrops start blooming, I would bring them some, as well as bread and apples.”

“Do your fellow villagers support you in this?”

“Who?! On the contrary. They say I have betrayed Ukraine! Not all of them, there is one woman. It’s as if I’m leaning towards Poland more than I am towards Ukraine. But why would I? I live in Ukraine. My parents are Ukrainians. Mom—Olena, dad—Kalenyk. I pray both for Ukraine and for Poland. I even mention Russia, saying: ‘Dear Lord, please bring those Russians to their senses!’” she sighs.

. . .And Matches

“Shurka, how are you not afraid?” her neighbor Olga often asks her now.

Once they both took a trip to the old Ostrówki cemetery.

“We arrived by horse. And we saw a Pole walking with candles from his car. He started yelling: ‘Your people scorched our people with fire!’ The neighbor got scared, took her horse and left. Later she told me: ‘And what if he’d had some kind of a revolver?’ But I went to pray and started talking to him: ‘Such were the times, what can we do now?’ We talked so much that later he brought me this raincoat. He was such a good Polish man, a salesman in a neighboring village, but he has left because of the quarantine,” Baba Shura complains.

She no longer goes to the cemetery with her neighbor. Only on her own.

“I recently went to a place which Poles call “Trupie pole” [the Corpse Field—R.]. And our people call it Trupy. Where do we go to pick berries? To Trupy! My Dad said it was because people died there and lay in the open for a long time. I went to clean up a bit, and Livon planted some junipers and blueberries. When I saw that they were drying up in the summer, I watered them with water from the ditch. And they survived,” Baba Shura says gleefully.

The territory of the former Wola Ostrowiecka is now called the Trupy tract. Her father Kalenyk Lukashuk was good friends with local families. He showed his daughter the graves of two Poles in the woods, and asked her to tend them. And “in due time, when the Poles come,” tell them “where their people are.”

When the USSR passed into oblivion, Baba Shura once met Leon Popek on the edge of the woods. And told him everything.

We take her on a trip to the cemetery in Ostrówki.

Along the way, Baba Shura vividly talks about 22 years of experience milking cows, about her grandson and daughter-in-law, who work in Poland and promise to come and help her chop up the firewood, about Witold, who once visited when the house was being whitewashed and “took pictures of everyone mudded all over,” about the bikers who persuaded her to get on a motorcycle (meaning the Polish Volyn Motocross Club, which organizes occasional races in Volyn towns and villages “in memory of the Volyn massacre”).

Among the graves in the Catholic cemetery, the “righteous traitor” first searches for the symbolic grave of Leon Popek’s mother, because she knew her personally. And reflects on the historical context. Once such a tragedy has occurred, the only thing we can do is pray, she says.

“They are forgiving, our people are not. I asked our Polapy priest: ‘Father, why don’t you go to the cemetery to pray when the Poles come?’ Let the others go, he says, why should I? He would never come here. Only Roman Catholic priests do. In the past, however, Ukrainian priests also used to come here. I think it is wrong: we should pray together.”

I ask if she knows why the Poles were killed and who killed them. She says that neither her father nor her mother ever said who did the killings. The only thing she heard, she says, is that, in revenge, the Poles burned the Orthodox church in the neighboring village of Polapy.

“Because they thought that it was the people from Polapy who set Wola Ostrowiecka on fire. At that point they were killing each other and asking no questions. . .” she turns silent.

Meanwhile, a car with Polish license plates stops by the fence of the cemetery. A large man asks in Polish if we have any matches.

“Nie ma, nie ma!” Baba Shura suddenly comes to life.

He uses a lighter to light the candles. I try to talk to him about the past. I confess: we are journalists, we take photos, we write. He doesn’t like it.

“There was someone here who used to tend these graves, so he was killed in Lviv. You know, there are good and bad Ukrainians, just as there are good and bad Poles. So, I would advise not to,” the stranger unkindly answers.

The conversation went nowhere. Somewhat embarrassed by the unusually unfriendly encounter, Baba Shura goes back to the house. She regrets that she didn’t bring any grave candles.

She has plenty at home. Says “Lion brought them.”

In the evening, she will close the curtains on the window of her house, feed the cats and the cow, listen to some radio. Then she will pick up her old and coal-black Gospel, look up at the icons. And again in her prayers she will be stronger than all the diplomatic and political judgments of the two countries having different readings of the same book.

And between those “readings” she remains, crucified.

“Baba Shura is a woman who does not think about herself at all, but about other people. I know that there are some in the village who say that she profits from the Poles. But what profit? They bring her candy, chocolates and all those things, and she gives it all away. And her tending the graves is genuine. Some people simply do not understand how it is possible to live for others. And she lives like that because that is who she is,” explains to me father Vasyl Bezyk, a local priest, later that day.

Oleksandra Vaseiko is a parishioner of his Orthodox Church of the Dormition of the Mother of God in neighboring Polapy. He knows that sometimes she goes to the Roman Catholic church in Luboml. But he doesn’t think that is a problem.

***

The only thing that helps Baba Shura in her difficult role is the compassion for others. And faith, as she keeps emphasizing.

She hugs us goodbye. Puts Szabłowski’s still brand new books, which we had just flipped through on a bench by her house, back on her wardrobe.

She gives us some cracked winter apples for the road.

“Baba Shura, aren’t you frightened living like this in a house, all alone?” I ask.

“Why would it? I am not alone. I am with my Saints. . .” she nods at her walls.

From every corner and windowsill, from her black with age icons, the Mother of God, Jesus, Saint Nicholas look at Baba Shura. Dry herbs mystically hang above them, collected and consecrated on Lord knows which Trinity.

Oleksandra Vaseiko from the village of Sokil in Volyn is standing under their eyes. In a green shawl, whose colors represent life. And a flowery blouse. “Trupie pole” has long been overgrown with such flowers. They bloom every spring at the foot of “Matka Boska” dug-out in the middle of arable land on the site of the burnt down Ostrówki church.

Baba Shura is one of those who collect and bring these flowers to the graves.

Such are her “machine guns.”

Tomasz Stryjek, historian, political scientist, leading Polish Ukrainian scholar, historiography specialist, and researcher at the Institute of Political Studies of the Polish Academy of Sciences (Warsaw):

&

“The mass killings of Polish residents, as well as the mass killings of Ukrainians in the villages of Volyn and Eastern Halychyna in 1943-1944 are referred to differently in the modern historiography of Poland and Ukraine. The dispute between the countries about these events stems from four distinct issues.

Firstly, the number of victims. Polish historians report about 100,000 Poles and 15,000-20,000 Ukrainians in the regions where the two peoples lived together at the time (Volyn, Halychyna, Kholmshchyna). Ukrainian historiography believes that there were fewer Polish victims—about 30,000-40,000. The problem here is that Ukrainian research is less thorough.

Secondly, in Polish historiography the main or even the only origin is the anti-Polish campaign of the OUN and UIA. The term ‘anti-Polish campaign’ was indeed used in the documents of these organizations at the time to describe actions aimed at removing Poles from the disputed territories. While the Ukrainians emphasize that the UIA forced the Poles to leave for the so-called ethnic Polish lands (beyond San and Bug), but never intended to kill them. Emphasis is placed on three sources of events: the struggle of the OUN and UIA for the independence of Ukraine as a territory with a pro-Ukrainian ethnic majority; the scarcity of land and seeking of retribution for discrimination against Ukrainians during the interwar period, which set Ukrainian peasants against Poles; the response to the killings of Ukrainians by the Armia Krajowa, which were committed by Polish self-defence units.

Thirdly, the rights to these regions. Polish historians believe that these regions belonged to the Polish state at that time, which abandoned them in favor of the USSR only in August 1945, and therefore had the right to defend them with the Armia Krajowa. But their Ukrainian counterparts are inclined to believe that belonging to a particular state depends on the dominant people in these regions. According to them, in 1939 to 1945 these were the lands of Western Ukraine.

Fourthly—definitions. The term ‘genocide’ in the legal sense was introduced into both Polish historiography and the legislature (Senate and Sejm resolutions in July 2016). But in respect to the term ‘Volyn tragedy’ frequently used in Ukraine, it is noted that it conceals the unequal level of responsibility of the parties. I.e., according to Polish historians, the OUN and UIA bear much greater responsibility than the Armia Krajowa.

Personally, I believe that the most accurate term is ‘ethnic cleansing’ by the OUN and UIA, which turned into a massacre of the Poles and, ultimately, Ukrainians.

After all, in 1943 an anti-Polish campaign was launched, which called for the removal of Poles from the disputed lands as an obstacle to independence and social justice. It is unlikely that it could come up to the killings on such a scale without the participation of the OUN and UIA. Irrespective of the dispute over the definition of the killings, there is a dispute over how to refer to the Polish-Ukrainian clashes in 1939 to 1947. Polish historians prefer the term ‘conflict’ due to the recognition that these clashes took place on the territory of the Second Polish Republic, while some Ukrainian historians prefer the term ‘Second Polish-Ukrainian War.’ Thereby they want to emphasize the independence of the OUN and UIA, while denying that these organizations were guided by a nationalistic ideology.

Summing up: for almost a decade, the relations between historians of both countries have unfortunately been quite bad. Only a few of them are willing to listen to the arguments of the others and build a holistic explanation of the causes of this crime. However, when it comes to mutual understanding among researchers, which means an impartial search for the sources of phenomena, one should never lose hope.”

Yaroslav Hrytsak, Ukrainian historian, publicist, Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor at the Ukrainian Catholic University, Director of the Institute of Historical Research of Lviv National University:

&

“I believe it was a genocidal act. But at the same time it is important to make one reservation: the retaliatory action of the Poles on the Ukrainians was also genocidal. Therefore, if we want to recognize the action as genocidal, then this recognition must take place on both sides. This means that Ukrainians also bear responsibility, and Ukrainians must admit this. But this recognition has to be mutual.

This act was not about the extermination of the entire population—it was to create a climate of terror—such fear that the local population would leave the region. This falls under the definition of genocide, because the term means not only complete physical extermination, but also the creation of conditions for a group of people under which they can no longer live in a certain area. When we take a look at the parallel act that took place in Pavlokom (and this was probably the greatest Ukrainian tragedy, when in March 1945 soldiers of the Armia Krajowa committed mass killings of Ukrainians from the village of Pavlokom in Subcarpathian Voivodeship of the Polish Republic), all the women and children who survived heard the orders or instructions from those criminals: ‘Go beyond the Zbruch and never come back.’ So their intentions were very clearly defined: the creation of an ethnically pure territory.

It is important to recognize that we tend to think that genocide is something like the Holocaust or the extermination of the Roma. I mean that the Holocaust or the extermination of the Roma is unique in the sense that they have no precedent, no comparison, because in this case it really was about the extermination of the entire group. We can say that the Holocaust was the perfect genocide. But in actual fact, most genocides are not perfect. Not like the Holocaust was. But even if they are imperfect, it does not mean that they were not genocidal acts.

I always believe that in such cases (this is not my position, but rather the position of the historiography to which I belong, and the position of the late Tony Judt, who is probably the most famous historian of our time, deferring to the position of Albert Camus) we must do our best not to try taking the side of the executioners and defend them, claiming that they allegedly had some personal right to do so. An honest historian must be on the side of truth.

In the Polish case, the position is half-honest. We have Baba Shura who defends Poles and tends the graves. And I would like there to be a Pole in Poland who would do the same for Ukrainians. Because otherwise we get the impression that only the Ukrainians are guilty, and the Poles did nothing wrong at all. This is simply false.

You know, Henryk Sienkiewicz wrote a novel entitled In Desert and Wilderness. It tells a story of two children roaming the jungle and meeting Kali, the leader of a local African tribe. They try to explain to him what good and evil are. And he explains his point of view: if a cow is stolen from Kali, it is evil, and if Kali steals a cow, it is good. The position of Poles and Ukrainians in this case is reminiscent of Kali’s philosophy. I believe that both sides are lacking courage. The Ukrainians do not have the courage to recognize the event as a genocidal act (instead calling it a tragedy or inventing some other ways), while the Poles say that there was only one genocide, moreover, a genocide of extreme cruelty.

In such situations, the most heroic act is simply to be a decent person. And Baba Shura is a shining example of heroism. A genuine modern day heroine. But sometimes she is used in a dishonest manner. I do not believe for a minute that there were no Poles who helped Ukrainians in the same way. I just don’t believe it. I believe that the Poles either do not want to find or show them. After all, in difficult situations, good people remain exactly who they are—good people.”

This story was written for the first printed issue of Reporters. Join The Ukrainians Community to get your own copy.

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More