Under One Dome

In 1943, the village of Yadlivka in Kyiv region was bombed by the Germans. It almost leveled the village to the ground. Only the church of the Blessed Virgin Mary survived. The villagers collectively built the five-domed wooden church in 1892.

But even earlier, in 1934, it was destroyed by the Soviets. In the Holodomor-ridden village, where a third of the population—up to 1,000 people—died of starvation, the Bolsheviks dismantled the dome of one of the largest churches in the Kyiv region. They destroyed the bell tower, toppled the domes, tore down the church decorations, and turned it into a school. During the Soviet era, the church served as a community center, and only in 1992, a hundred years after its construction, it was restored as a church.

The locals consider it a miracle that the church did not burn down during World War II. After the war, the village was renamed to Peremoha, meaning Victory. Today, the villagers recognize that the name is reminiscent of Soviet propaganda, but they do not want to change it. They say it is prophetic. They fear that changing it may bring misfortune.

*

But at the end of February 2022, disaster was unavoidable. What the Soviets did—destroying the church— the Russians attempted to replicate.

About two and a half thousand units of Russian military equipment were moving along the road past the village, toward the capital. But they couldn’t pass through. In the village of Rusaniv, 24 kilometers from Kyiv, the territorial defense blew up a bridge. The occupation of Peremoha, which lasted from the last day of winter until March 30th, was not “quiet”. A column of cars attempting to evacuate through the “green corridor” was fired at. Seven people died, including a child. Local men were tortured and executed. Nineteen houses were destroyed.

Local historical heritage, a monument of 19th-century wooden religious architecture, also suffered. On March 5th, the Russians destroyed the Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary with a direct hit.

“They said that our spotter was sitting under the dome—that’s why it is shot up like the starry sky,” says the priest of the church, Father Oleksandr, pointing up.

The dome cannot be restored—for now, only the floor has been repaired and the walls patched up. Father Oleksandr did not want to undertake a full restoration until the war was over. But the first donation for the restoration was given by a local soldier who would not take no for an answer, and the villagers set to work. All together.

Not that the village was very religious. “You know, we have a saying: after victory, we turn to God,” says Father Oleksandr. But just as two centuries ago, they built the church together, in the spring of 2022, united, they fought the enemy, mourned the dead, and supported each other.

70-year-old Lydia Oleksiivna, who survived the occupation in one house with six occupiers, buried young people shot by the Russians. Later, when little would remain of their bodies, she would be the only one who would be able to recognize each of them. Oleksandr Yarmolchyk, a priest who, together with his parishioners, took the church from the Moscow Patriarchate in 2019 and returned it to Ukraine, held services until the day the church was hit. A volunteer named Svitlana turned the house near the church into a volunteer hub.

If history really repeats itself, Peremoha is proof of this theory. If you believe that old buildings retain historical memory and energy, the wooden church seems to have made the village a center of love and sacrifice.

“You buried mine, and I buried yours”

Lydia Oleksiivna could not stop the Russians from entering her home: there were six of them, and she was alone, unarmed, and scared. They found her hiding with her cattle in the barn and asked to come inside.

“How can you live like this?” they asked me, looking around the house—three of them stayed on the doorstep at first, and the other three went inside. I got scared. “Live like this”—what do you mean? “It’s a palace!” they said. They pointed at my bathtub and asked, “What kind of trough is this?” I thought, good God you are completely clueless. This is just an ordinary run-down village.

The thin and petite 70-year-old Lydia invites us into her home. The modest house is neat and clean, the floors are covered with carpets, and the walls with icons. Since her husband passed away and the children and grandchildren moved away, she has been taking care of the house, livestock, garden, and a few cats, all on her own. The room is lined with rows of toys and children’s things, untouched, waiting for the youngest visitors to arrive.

Lydia Oleksiivna has been living in Peremoha for 34 years—she moved here for her husband. And when he died of epilepsy, her friends started saying, “Lida, you should get together with Komor.”

“His wife died in an accident, and after her death, he was left alone with three young sons. I had three daughters. I felt sorry for his children, moved in with him, and that’s how we became a family of six,” she explains.

She told the same story to the occupiers. When they asked her how many children she has, she proudly replied: twenty-seven. “Well, your husband must have been quite the ladies’ man,” they laughed. And she would explain: first there were three, then there were six, they all got married, then grandchildren and great-grandchildren came along, and so it became a lot. But she faced the Great War alone. More precisely, hiding with all the livestock in the barn.

Three cows, three pigs, a horse, a goat, and chickens—in addition to her own animals, she takes care of her son’s. Every day, as she walked across the garden to the barn, she would recite the Lord’s Prayer to herself. “Guys, you’re not going to kill me, right? If you’re planning on it, do it right away so I don’t suffer,” she would say to the occupiers over and over again when asking for permission to go to the livestock. They said they don’t harm civilians. “Then, boys, the order will go as follows: I am your mother, and you are my sons. Agreed? You won’t touch me?” she negotiated. And that’s how she lived, flinching from each explosion as she crossed the garden, repeating the prayer.

“How are you?” “the boys” would ask.

“Every day is better than the last,” she replied sarcastically, “the ground is shaking, my soul is hurting.”

“That’s life,” her temporary roommates shrugged, who also didn’t know how to communicate with a woman whose house they had occupied by force.

On March 1st, the second day of the occupation, Lydia Oleksiivna received a hysterical phone call from her daughter Larysa with the news of her son’s death: “Mom, did you know that Rusik was shot?”

“My grandson is there, they shot children there,” she cried and begged the occupiers to take her to the Nova Poshta, where local men, including her grandson, were executed on the last day of winter—the Russians grabbed all men they saw on the street, took them inside the post office, and interrogated and tortured them.

The commander said, “You can’t go there. Our superiors will shoot you there,” and they would not let her go.

The chance to see the execution site came only ten days later. Lydia waited until “her orcs” left and convinced her neighbor to go to the post office—no one was guarding the center of the village that day.

They searched the village and its vicinity. The bodies were gone.

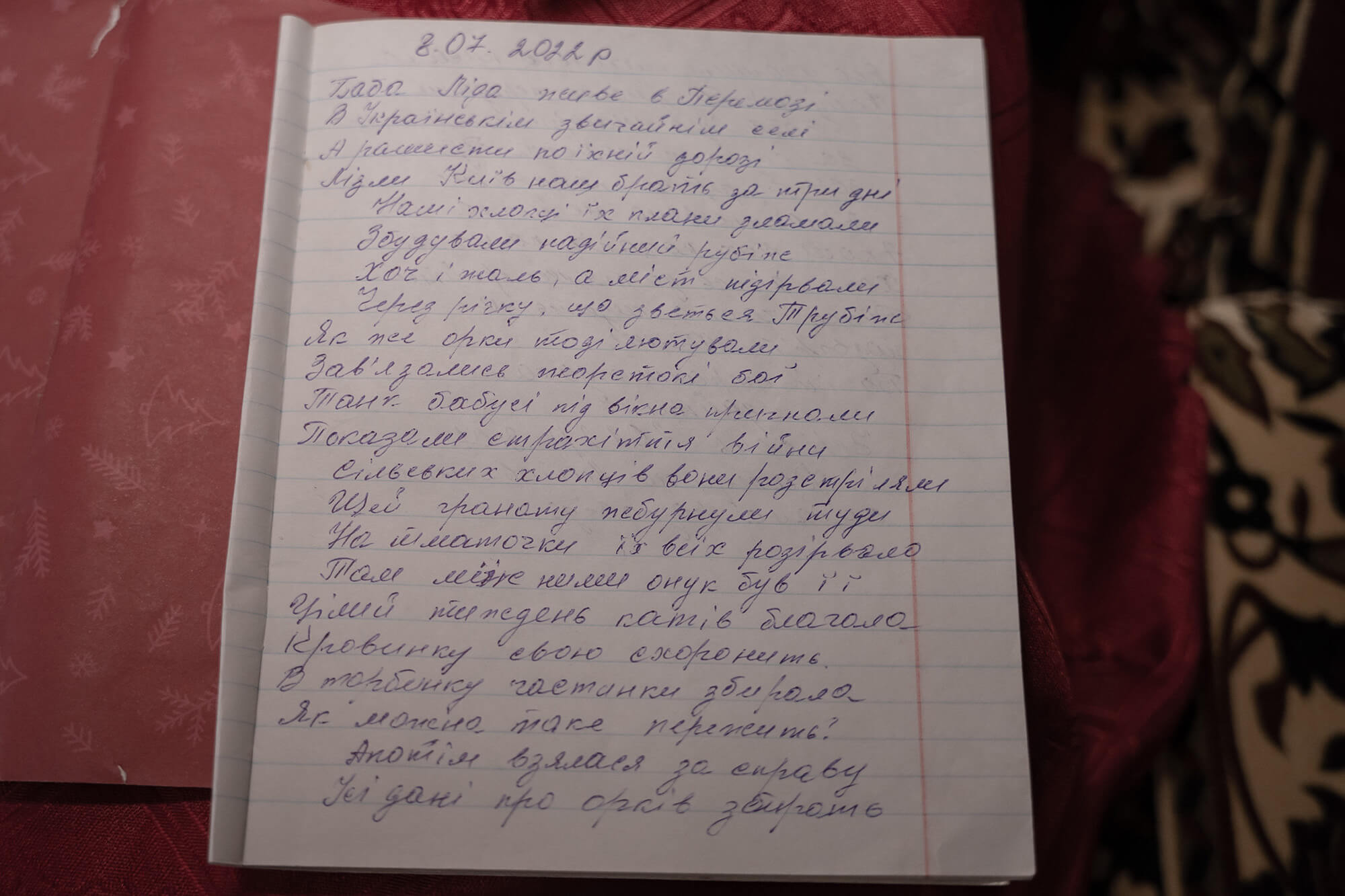

She stayed sane by using a “zoshit”, an ordinary lined school notebook, in which Lydia Oleksiivna wrote down everything she saw and felt every day in neat, legible handwriting: where things exploded, what kind of military equipment passed through the battered rural streets. She wrote about the weather. She cursed the “orcs”. She mourned her Rusik. He was about to turn 28.

She wrote about how she still had electricity in her house when her neighbors didn’t. Then she invited them to her house to connect their power generators and fill up on water. The Russians protested, “You can’t do this, you have to ask for permission.” Lydia Oleksiivna got even more outraged, “They have small children! You charge your gadgets here, and this is my home.”

Nazar from St. Petersburg, one of the youngest occupiers, treated Lydia Oleksiivna most favorably. She learned everything from him: when the occupiers were sent reinforcements, where tanks were stationed, and when it was time to hide. She would say to him, “Nazar, don’t lie to me, God sees everything.” One day, she reported Russian positions to the Ukrainian territorial defense by calling a friend. And the Russian checkpoint was gone.

“We were sitting by the summer kitchen, and I started this political discussion with them. I told them, “Guys, couldn’t you just give up? Go home? You would stop bothering us with all of this.” They said that they would be shot. I told them that I had never seen anyone more stupid – 10 thousand hryvnias is real money for them. They’re dumb, fools—from Samara, Chelyabinsk, Ufa, from the Moscow region. Well, okay then. Let them rest in peace,” Lydia dismisses.

“They drove their tanks straight through. Through gates, fences, vegetable gardens. And one day their tank got stuck in the cornfield. Only the barrel was sticking out!” she recalls.

This is how she kept going, trying to coexist with the enemy and pouring her heart out in her diary.

“Guys, at least don’t break the jars,” she would say when she saw them taking preserves from her and her neighbors’ cellars. “They tore the locks off the cellars, but didn’t break the jars.”

“Guys, you parasites, don’t cause harm. We’re in the village.” They replied, “We’re not causing harm, the others are doing it.”

Four days after the unsuccessful search for the bodies, Lydia Oleksiivna and her neighbor went to the post office again. The dead bodies appeared out of nowhere.

“Rusik, Yaroslav, Dima, Seryozha, Sashko,” she counts on her fingers. She didn’t recognize everyone immediately—they were identified later.

“Rusik—headless, armless, and missing a finger. He was in his underwear, and his jacket was pulled up. Legs intact, sneakers falling off his foot—I put them back on.”

“Seryozha Yareshko was in overalls. He was missing a leg and an arm. Dima Koval was intact, but he was beaten up. I also recognized Yaroslav. He was missing a leg, an arm, and a head. They were wearing boots. We dug a pit, put them all in bags, and buried them like that,” she recalls.

The same day, with a heavy heart, Lydia Oleksiivna left the village for her daughter’s house via the “green corridor”—her neighbor persuaded her to do it. During the day, she worked as a nurse, and at night, she cried for the boys.

When she returned to the liberated Peremoha, there was an exhumation in progress. Lydia was very worried that the men would not be buried properly—and she was right. She came to investigate along with the mother of one of the deceased.

“Why did we drag all those bags?” she says. “I explained to them, “This one had no right leg, that one had no left leg. Ruslan had two legs, and Dima had two legs. Only Dima was wearing boots, and Rusik was wearing sneakers.” They were yelling a lot. I told them, “Cut the bags open and show me. Really. You buried mine, and I buried yours.” And then they reburied them properly.

In the end, the woman recites the Lord’s Prayer.

Lydia has 27 children. She “adopted” six during the occupation in order to survive. She took care of another five, including her own grandson, in a motherly way on their last journey, so that they could sleep peacefully.

Bees

43-year-old Svitlana Kryvulska also took care of other people’s children in peacetime. She ran a children’s cafe in Baryshivka, where people gathered to celebrate birthdays and family holidays.

But then, the massive cream-colored sofas and modern wooden tables from the Baryshivka cafe, Vanilla Courtyard, were moved to the Peremoha Orthodox Church. The church was not intended for this purpose, but today, local “bees” weave camouflage nets and pack food and all the necessary humanitarian aid for the front. Svitlana’s husband, Pavlo, has been in the military since February 24, 2022, and is currently in the east, so she has no time for vanilla.

“It’s very active there. If we weren’t doing all of this, we would go crazy. And this way we help them, buy them cars, weave nets, and make food. They share those rations, sitting underground while they’re being covered with phosphorus and shelling. They can’t cook. That’s why we do it,” she says while weaving.

While Peremoha was occupied, she cooked for the troops in the Vanilla Courtyard. In the same cafe, where children’s trampolines used to be, soldiers slept—Baryshivka was their headquarters. Two other establishments from other villages did the same, and together they delivered food to checkpoints.

“As soon as the passage to Peremoha opened, we immediately went there with packages. We did that for two weeks. We reached a house at the edge of the village, where an elderly woman lived. Father Oleksandr started calling her name, and only then did she come out of the cellar. For two weeks after the liberation, the poor woman sat there scared,” recalls Svitlana.

She lives in a house that was destroyed by the Russians with her five-year-old son David—the roof and veranda are smashed, and windows are blown out. But Svitlana has neither the strength nor the desire to repair the house, “My husband will come home, and then we’ll rebuild it.”

She doesn’t know the locals very well—she moved here five years ago when she was pregnant and dreamed of life in the countryside. She ended up in Peremoha by accident—the GPS took her to the wrong village. To Kashtanova Street, where an elderly woman was selling her house.

“We entered the courtyard, and everything looked so cozy and homey, that I didn’t want to look anywhere else. No toilet, no running water, nothing—just a beautiful green courtyard, old pear and apple trees. I fell in love with it. The child was born, the coronavirus started, and there we were in our yard, in nature, with our chickens and goats. I wanted to run a household!” Svitlana recalls with a gentle smile while blankly looking at the windows of the house covered with plastic, where she only comes to eat and feed her child. During the occupation, a Russian commander lived in her house.

She cares more about the volunteer headquarters in the building near the church. Father Oleksandr built this building, hoping to provide the children of Peremoha a place for hobby groups, Sunday school, and something like a cultural center.

“There were benches, a stage. The kids and I organized concerts for people. It was such an ordinary life,” the priest recalls bitterly.

A benefactor helped with the renovation, Svitlana moved the furniture made by her husband, and others provided materials—thus creating a place of strength where they work from morning till night. From the wall, a photo looks down at the women, a collage of local soldiers with children.

“As you can see it’s not expensive,” the volunteer says, as if justifying herself. But she is proud of the photo, which she designed herself.

At first, the Peremoha volunteer kitchen, where they made dry rations and energy bars, was based in the school. But they couldn’t work there permanently because there was not enough space. At the beginning of the war, they barely managed to negotiate with the owners of the building where the cafe was located to not charge rent. Then she thought about the house near the church, which was vacant, but was damaged when the church got hit and needed investment. Her conscience didn’t allow her to raise money for this—she only raised money for cars for the military, night-vision devices, and anti-drone guns. Svitlana and her husband maxed out their credit cards in the first days of the war at the only working store, buying everything that was needed for the village and the checkpoints.

And then Svitlana had a dream: a large angel in white robes stood before her and asked how things were going at the house near the church.

“I tell him: I’m just scared. I tell him about our energy bars and the cars, and that we have a lot of work to do. He gives me a bundle and says, “This is for everything you desire. Just don’t stop.”

She listened. She posted on social media that she was selling furniture and appliances from Vanilla Courtyard, explaining the needs. People started donating money. None of them took anything in return. There was even enough money to pay off her loans.

Now, the “bees”, as Svitlana affectionately calls them, have grown into a charitable organization producing thousands of meals in workshops in different villages. The volunteer is upset with the local authorities because, according to her, they do not provide any support. The organization is supported by people from the community and from all over Ukraine. They help the “bees” stay sane while waiting for their loved ones to return.

“My child has barely seen his father for two years. We have to live on our own, wake up, work in the garden, fill up the cars, and chop wood. My house doesn’t have gas heating. I have to get the firewood myself and heat the stove. And when we come home from work to a cold house, there is no one there to heat it… If the authorities in a community support the volunteer movement, you immediately see that we are all fighting for this victory together and can move mountains together. Here, we do everything ourselves to keep ourselves from going crazy,” she says passionately, holding back tears.

Men in military uniforms silently gaze at Svitlana from the photos. In the next room, Jesus graffitied on the wall, watches as women weave green ribbons into a large covering as they talk. A biblical story could be written based on this scene.

Chess

“There are daredevils who were in combat, and thank God they found themselves. But the truth is, as our commander-in-chief says, wars start with soldiers but end with teachers, engineers, and everyone else. Relatives of the deceased come to me all the time. They come on Remembrance Day, we go to the cemetery and hold service there. Once we had a requiem, recalling how it all was. War is not just a game of chess, it’s also chaos, and you can never say that it’s better or easier for someone in it,” Father Oleksandr says quietly, gazing at the “starry sky” of the pierced wooden dome.

During the occupation, right after the church was hit, six Russian soldiers stormed the cellar where the priest was hiding with his family. They sat down on chairs next to them, as if it were a normal thing to do. One of the Russians asked, “What is the difference between the two churches?” And he answered himself, “The offices are different.” “So be it,” said Oleksandr. If Lydia Oleksiivna had been with him, she probably would have said without hesitation, “My God, I have never seen stupider people than you.”

Father Oleksandr has been helping the army since 2014. “We have taken so many cars to Kherson, he has carried and loaded so many,” local volunteers recounted. But he doesn’t talk about it himself. Silent and tired, he just returned from sending off a fallen soldier in a neighboring village. He’s already done about five dozen such send-offs. This work is impossible to get used to.

In the turbulent few months after the de-occupation, he didn’t even think about reconstruction. But, like Svitlana and her GPS, destiny had other plans.

“We wanted to rebuild after the war, to restore the wall, to preserve it, not to touch it,” he says, “because we raise money for the guys to buy them things they need.”

“Then our soldier, Zhenya, came. He gave us 15 thousand for the church. I didn’t take it, I said, “Buy something for the unit.” He gave it to the accountant. And what could we do with the money? We started doing something to keep the money from depreciating. And once we got started, there was no stopping it.”

The state and foundations have not yet helped a single destroyed house in Peremoha, and locals feel the pain of this abandonment. But people, eager to recover from the occupation as quickly as possible, have already set up a war museum in the school, with photos of the destruction, shell fragments, a memorial wall, and damaged icons from the church. Local men are helping to rebuild the church. The villagers come here not for prayer, but for the physical feeling that they can at least heal these walls.

Of course, no memorial, a restored church dome, or even a hundred recitations of the Lord’s Prayer can bring back Peremoha’s fallen soldiers. But they do what they can to support those that are still alive.

***

«Healed Lands. Зцілені землі» is part of «De-occupied: Stories of the Liberated Territories», a project supported by the Heinrich Böll Foundation’s Bureau in Kyiv, Ukraine. Its goal is to show that Ukrainians are not giving up or waiting for outside help but are bringing life back to their communities and homes. Even though the war continues.

In these texts, we report on the renewal of life in Ukrainian territories that used to be temporarily occupied or besieged by the Russian army. We publish stories based on personal experiences of war—about people who find the strength to go on living and pass that strength on to others. About people who lead by example, inspire others, or help villages and towns recover from the war through their initiatives.

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More