The Way Home

Police in the Chernihiv region recently reported that 14-year-old Serhii Sorokopud, who had been forcibly taken to Belarus by the Russian occupiers, had returned home to the village of Yahidne. Many concerned people joined the difficult mission to return the boy to his family, including the journalist who recorded the story. Serhii is already at home, but no one yet knows how many more Ukrainian children have been forcibly displaced abroad on their own by the Russians.

“Did it hurt a lot?”

“No.”

“Was it scary?”

“No.”

“Are you hungry?”

“No.”

“Do you want me to buy you some water?”

“No.”

14-year-old Serhii Sorokopud stays silent all the way from the Kyiv railway station to his native village of Yahidne in the Chernihiv region, giving one-word answers to each question. The boy’s face looks like a mask. Is he trying to come off as strong, as an adult? Or has he experienced so much stress that he is unable to express his emotions? Or maybe he is simply exhausted from the journey. Together with his 25-year-old sister Alina, he was on his last leg of a trip from Gomel, Belarus that had taken more than a day. They were lucky to come across acquaintances at the border, who made an exception and let the siblings pass directly from Brest to Kovel. After all, Ukraine’s borders with Belarus are now closed.

Having met Serhii and Alina at the Kyiv railway station, we are now driving them home. Soon our old Jeep stops on the outskirts of Yahidne, by an old house. The Sorokopud family have been living here since April—their friends let them stay here. Serhii hugs his mother and picks up his younger brother and Alina’s son. The boys are almost the same age, both are not yet eight. And suddenly a miracle happens right before my eyes: Serhii’s radiant smile lights up not only his face but everything around him. Even a burnt-out Russian armored personnel carrier lurking in a neighboring garden—an ugly reddish-black monstrosity—no longer looks so depressing.

“I don’t know how I feel,” the boy tells me unexpectedly. “Many things. . . I just can’t describe it all in words. The main thing is that I’m back home!”

In the first days of March, the Russian invaders entered Yahidne. During the shelling, Serhii Sorokopud suffered severe shrapnel wound, and the Russians took him to Gomel, Belarus, without his parents’ permission.

“He received surgery there. Sure, they saved my brother’s life, but if they hadn’t come to ‘liberate’ us, my brother would never have been injured. For almost a month we didn’t know if he was alive. And a week ago a lawyer from the Gomel hospital told us that if we didn’t pick him up within seven days, we could kiss our boy goodbye. The Belarusians would register him in an orphanage, recognize him as a ward of the state—with living parents!—and would not let him out of the country until he comes of age,” says Alina.

We talk in the yard under a large apple tree in blossom. The wind tears the flowers from it, and snow-white petals fall on the young woman’s dark hair. Against this fairy-tale background, Alina’s words sound dreamlike. Just like the wrecked enemy ZIL trucks and armored personnel carriers inscribed with the letter ‘O’ that are scattered all over the village, surrounded by red tulip heads.

A Cold March in Yahidne

In early March, a missile hit a high-rise building where the Sorokopud family lived. There is still a huge hole in the bedroom ceiling, through which the sky is visible. The Sorokopuds were lucky that when the missile fell, they were all in their living room and kitchen. When the ominous whistle cut through the air, they jumped on the sofa together, hugged and covered themselves with blankets. Why? None of them can answer this question even now. They spent the next night in the basement. The explosions shook the ground beneath their feet, but it was too late to escape. Nor had they anywhere to go. In the morning, a neighbor came. She said that Russians had entered the village and that all the civilians were being evacuated. She told them to get ready. The Sorokopuds obediently packed their bags. They now had no place to live anyway.

“In the evening, an Ural truck came to our house with a cross painted on it. That was the first time I saw Russians. Burly men in dark green uniforms, with machine guns and red arm and leg bands. First they took our phones and tablets, and then ordered us to quickly get into the car. They didn’t say where they would take us,” Serhii recalls.

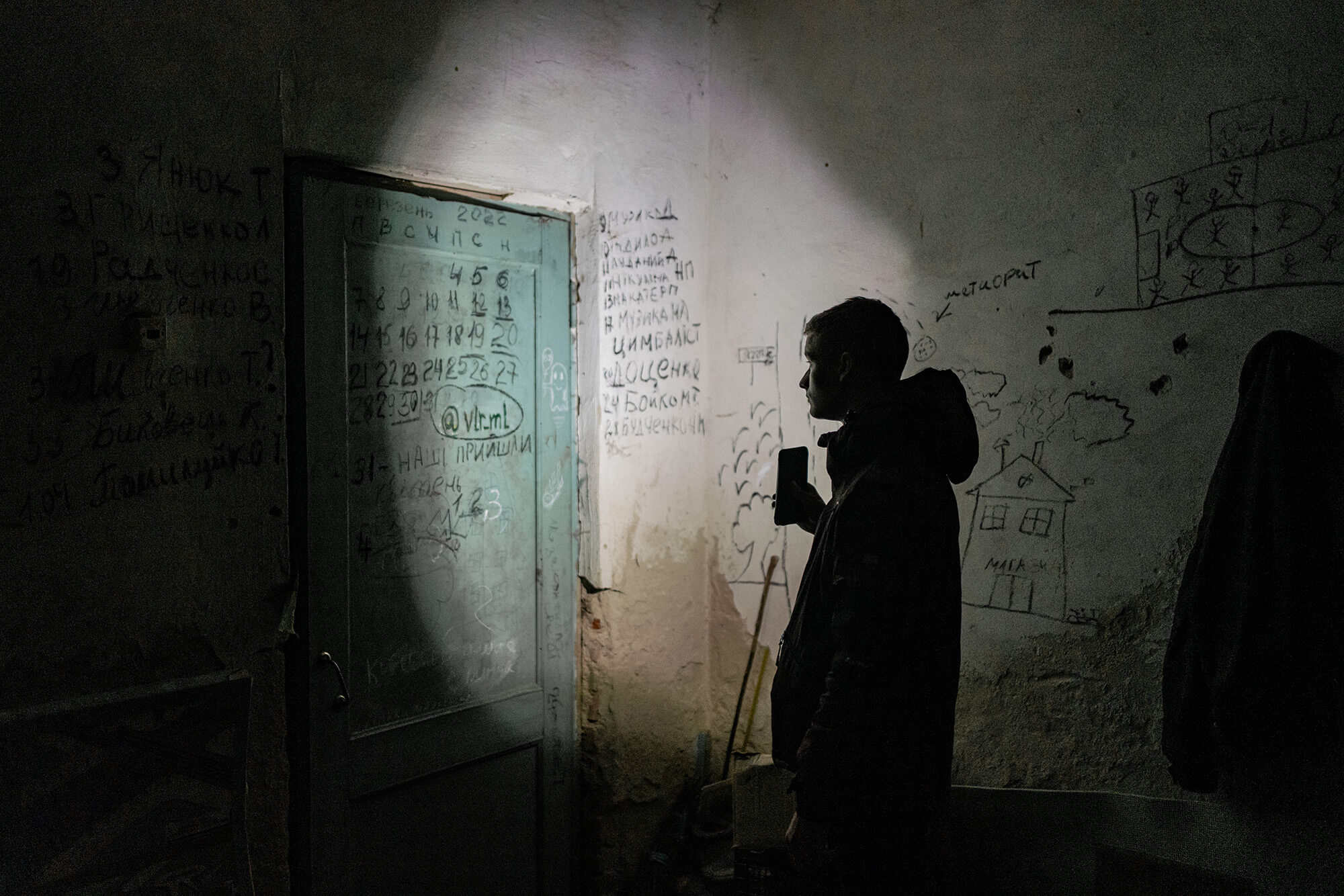

Deceptively calling it evacuation, the invaders gathered all the people from the village in the basement of the Yahidna school. Those who did not want to go willingly were led there at gunpoint. All men were not simply searched but stripped to underwear. The Russians hoped to find out from their tattoos whether they had served in the army. When everyone was there (a total of 360 people, including 80 children), the basement was locked with a huge padlock. The Nazis did the same to Ukrainians during World War II.

“In the evenings, the Russians got drunk, came down to the basement and threatened to shoot us all,” says Serhii. “One of them, waving a machine gun, told me, ‘I’ll kill you, son of a bitch!’ And for some reason, I wasn’t even scared. I don’t know why.”

At first, people ate what they had taken from their homes but they soon ran out of food. Then the Russians began to give them their MREs. One for three or four people. Later, they brought several bags of cereal, which smelled terribly of diesel. But the inhabitants of Yahidne did not care: anything not to starve to death. The tiny portions were not enough to keep the kids fed. They cried, asking for food. But there was nothing to give them.

“In the morning, the occupiers would usually let us out of the basement to go to the toilet. When our food ran out, we asked them for permission to cook something from their MREs on a campfire outside. They agreed. But then they would lock us up for the whole day and didn’t even let us go to the toilet. On such days, cooking was not an option; we simply starved,” says Alina.

The people of Yahidne did not know that while they were cooking diesel-flavored cereals over the fire, the invaders were looting their homes. First, they took all the food. Then household appliances. And finally bed linen, clothes and shoes.

“They even took our underwear,” says Svitlana Sorokopud, Serhii and Alina’s mother.

Due to her mobility issues (the woman can barely walk), Svitlana did not have to go down to the basement. She spent the entire occupation in the apartment of her old bed-ridden neighbor. Shells and missiles were flying overhead day and night. In between the shelling, the armed occupiers would break into the apartment to check if there was anything else that they could steal. According to Svitlana, they were mostly Tuvans. The Russians would only take gold or computers. One of them took pity on the women and brought a bowl of soup for both of them once a day.

“That portion would fit in the palm of your hand. But I was so anxious I couldn’t eat. So I gave the soup to the old lady,” says Svitlana.

At that time, Svitlana was most afraid for her daughter. Alina is a good-looking girl, and the occupiers were looking to have a good time. They fired into the air and demanded a ‘female for the night.’ Svitlana’s 42-year-old friend was seized and taken out of the basement, but the commander ordered the soldiers to let her go. The drunken Tuvans grabbed Alina by her arms on several occasions. Fortunately, nothing came out of it.

However, it was the elderly who had it the worst. In the cramped basement, everyone had to sit on chairs. There was no air to breathe. Due to the lack of oxygen, the old people got weaker and weaker every day and were losing their minds. If possible, they were taken to the school storage room. But this didn’t help. Ten elderly residents of Yahidne died without returning to their homes.

They could not be buried. During the day, the village was shelled, and at night, the Russians did not let anyone out of the basement. In addition, most of the prisoners contracted chickenpox and were running a fever in the basement without medication.

“Blood, Chunks of Skin and Flesh”

On the morning of March 13, Serhii Sorokopud came up from the basement to get a glass of boiling water from the fire. While he was waiting for his turn, there was an artillery strike. A loud bang, and the boy fell to the ground. Alina ran over to him. When she turned the boy on his stomach, blood came out of his mouth.

“I managed to take Serhii’s jacket off and saw blood, chunks of skin and flesh. . . I felt sick. I dragged my brother to the Russian field hospital. There was heavy shelling at the time.

Windows were breaking in the school building. They washed and dressed Serhii’s wound in one of the classrooms, gave him an injection and put him on a drip. And then they sent us back to the basement,” the boy’s sister recalls.

The next morning, the Russians with the call signs Spider, Maple and Deaf called Serhii up to get his wound re-dressed. Alina and her father took her brother to the field hospital, after which the young woman returned to her son in the basement. And when she went upstairs, she heard the terrible news from her father: Serhii was being taken away. . .

“I rushed to the Russians. My brother was standing by the car. I told the commander that I was going with him. But in response he said that there was no place for me. He told me to choose between him dying here because the wound was so deep, or them taking him to hospital. I had to let my brother go. But I managed to slip his birth certificate under his T-shirt. I didn’t know where they took him. The Russians never told me. . .”

Late at night, in the pitch darkness, the car that had taken Serhii away arrived at a meeting point in a field. Shortly after a helicopter for wounded Russians arrived there. It took Serhii to Gomel. Together with the soldiers, he was then sent by bus to the Gomel Regional Hospital. The doctors examined his wounds, and two weeks later, he was operated on. A severely wounded old man from a nearby village was in the ward with the boy. Serhii knew him before the war. But the man did not have the strength to talk, and the boy does not know what happened to him.

At around that time, the Russians left Yahidne, leaving behind a village blackened by soot, almost completely destroyed. Alina came down with chickenpox, running a 40°C fever in the basement of the school—there was nowhere else to go. They ran out of food. There was no electricity, gas, water or transport in the village. The connection with the outside world had been cut off: the Russians smashed the phones and tablets, and volunteers could not get to Yahidne due to heavy mining in the area.

“I asked my husband about Serhii. Whether he managed to feed him. And he told me that our dear Serhii had been taken somewhere. . . At first, I didn’t even believe him. What does that even mean, ‘taken’?! How is that possible? Because of the occupation, I learned only two weeks later that my son had been abducted!” says Svitlana.

The neighbors told Alina a few weeks later that some nurse from Gomel had posted on Facebook about a boy looking for his parents. The photo showed Serhii and his birth certificate. The Sorokopuds found a phone and contacted a relative in Belarus. At their request, the woman bought a mobile phone and went to the Gomel Regional Hospital, where she met the boy and handed it to him. For the first time in a month, he was able to talk to his family.

“Our Serhii is very brave. He didn’t even cry. He just wanted to go home. But he was transferred to the Gomel Regional Children’s Hospital for rehabilitation. We were told that if we came then to get him, he would not be released,” Svitlana says with a sigh.

There were other young Ukrainians in the ward with Serhii. A boy from the Chernihiv region with shrapnel wounds to the knees. A teenager from the Zhytomyr region, who suffered the effects of a landmine explosion, with severe injuries to his arms, legs and eyes. There was also a woman from the Kyiv region with her daughter and son. The shelling injured the girl’s legs and the boy’s stomach.

Not Without Kind People

The storm erupted suddenly. A lawyer from the Gomel hospital told the Sorokopuds that Serhii’s parents needed to pick him up within a week. Svitlana was unable to pick her son up because she could barely walk. The boy’s father is eligible for military service and so cannot leave the country. Alina had to get a power of attorney from her parents who instructed her to pick up her brother.

That same day as I arrived in Yahidne, Alina returned from the notary. She has only left her village to visit Chernihiv and Kyiv a few times in her entire life.

“I’m afraid of getting lost in the Kyiv underground,” she complained to me.

I confess that I tried to talk the girl out of the trip. Let’s contact the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, I said. What if you get arrested in Belarus? But Alina did not want to hear a thing.

She was going to get her brother—come hell or high water!

She called from Kovel. First, it turned out that the border with Belarus was closed. One has to go through Poland. Secondly, one can no longer enter Belarus without their international passport. And Alina did not have one.

“What should I do? I only have three days left! Help me!” she said.

“Return to Kyiv,” I said, taking a chance.

Of course, I knew that it was impossible to get an international passport in the snap of a finger. Nevertheless, I decided to call some senior officers at the State Migration Service of Ukraine through their press service. And the head of the Service, Natalia Naumenko, told me that “she would do everything she could within the law to resolve the issue.” It turned out that miracles do happen. Employees of the State Migration Service of Ukraine in Kyiv went to work on a weekend and made a brand new international passport for Alina in just a few hours. Having carefully put it in her bag, she hurried to the train station to buy a ticket to Lublin. However, a new obstacle awaited Alina in Poland. Due to the war in Ukraine, all trains and buses to Brest had been cancelled. Alina had to get to the border by any means possible or walk over 100 km. . .

Ukrainians from Eastern European Reformation, a Christian organization, helped her.

After my call, Svitlana Chernivska (her husband Viktor was captured and imprisoned by the invaders in Luhansk in 2014 for taking civilians out of the occupied territories) picked up Alina in the Lublin railway station, fed her lunch and drove her to the border checkpoint. On the other side, at Svitlana’s request, the girl was met by Belarusians sympathetic to Ukraine. She spent the night with them and went by train to Gomel. Fortunately, she had no problems crossing the border.

Then another Belarusian helped her out. My friends advised me to seek his assistance. At first, I asked him to search for a driver who would pick up Alina in Brest and take her to Gomel. But he didn’t manage to find anyone. Instead, he decided to buy Alina round way train tickets. Except for his username on Telegram, I know nothing about this man. In Lukashenko’s land, people are afraid to say their real names. But the Sorokopud family are very grateful to this Belarusian.

“The journey back to Ukraine was difficult for Serhii and me. The doctor at the Gomel Children’s Hospital turned out to be Ukrainian. And on my brother’s medical discharge report (in the header of the document), he wrote, ‘Glory to Ukraine!’. I am grateful to him for his support. But because of this, the Belarusian border guards searched and checked us for four hours,” says Alina.

Meanwhile, his parents, friends and neighbors were looking forward to the boy’s arrival in Yahidne.

“Did I know that we would get Serhii back? Of course, I felt it in my heart. But when he was taken away, I stopped sleeping. Now I’m finally going to catch up on sleep,” says the boy’s mother, covering her eyes with her hand from the blinding sun.

Spring this year was especially torturous and bittersweet. The wait for the summer heat was long and painful. Maybe because we had the faint hope that its arrival would chase the war away. In the end, we were wrong—this war is not going to end anytime soon. But I believe that at least for the young Serhii Sorokopud, the war’s horrors are finally over.

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More