The March of Life

Today, the territory of the former Janowski concentration camp and Jewish ghetto in Lviv is a typical city neighborhood. There’s little here that calls to mind the events of World War II and the extermination of the city’s Jewish population. Two weeks ago, participants in the March of Life walked the Lviv Jews’ “road to death.” Their gathering, the organizers say, was not political. For them, what’s most important are the meeting, reconciliation, and healing the earth.

Bloody Silence

The town of Tübingen in Germany is famous for Eberhard Karls University. Duke Eberhard founded the university in 1477. That same year, he drove all the Jews out of Tübingen. Jewish life returned to the city only in the 19th century. However, in 1933 the persecution started up again—all employees of Jewish heritage were fired from the University of Tübingen. This was the first such precedent in all of Germany. Thus, this small town became the theological center of antisemitism. Criminals from Tübingen, students, and professors led to the death of more than 700,000 Jews all around the world.

“When I look at myself in the mirror today, I think about the fact that I look like an SS soldier,” says Matthias, a tall twenty-year-old man with short, fair hair. “I used to think that I was in no way involved in the Holocaust. I felt indifferent toward it. But a few months ago, I found out that my great-grandpa was a member of the SS. He was here, in Ukraine, which means he participated in the extermination of the Jews. This wasn’t just anyone, it was my great-grandpa!”

Matthias came to Lviv with a group from Germany to take part in the March of Life. The Catholic community group Living Fire and the Association of Charismatic Churches of Ukraine invited them to Lviv. Similar walks have taken place in more than 15 countries. Their goal is reconciliation between those who survived the Holocaust and the descendents of those who were guilty of this tragedy. The first March of Life took place in Germany in 2007. It followed the road to the Dachau concentration camp.

“There were eight concentration camps around the city of Tübingen,” says Hans Reuß, the international director of March of Life. “At the end of the war, they ran out of fuel there. The prisoners whom they didn’t have time to kill were forced to walk, the so-called ‘march of death,’ more than 200 kilometers to the concentration camp in Dachau. They died—from hunger, cold, and exhaustion. This happened right outside our windows, but for a long time we pretended like we hadn’t heard anything about it. But one time during prayers at our church, the Lord revealed the following words to us: ‘The silence of your parents and grandparents is now in you.’ In Germany, like in Ukraine, we still live in the shadow of the Holocaust. If we take a close look at our history, we can see that in our families there are either criminals or victims or those who looked on indifferently as the Jews were exterminated.”

Lviv’s Poisoned Landscapes

“Ania, look how many of us there are!” a gray-haired woman says to her younger companion. The women are walking along with the dense, motley crowd from the Klepariv train station, past the former Janowski camp, to the area of Pisky—the road to death for Lviv’s Jews.

Today the territory of the former labor camp and Jewish ghetto in Lviv is a typical city neighborhood. There is little here to remind one of the extermination of the city’s Jewish population during the Nazi occupation. Waitman Beorn, who studies the Holocaust in Eastern Europe, sheds light on this tragic place.

During the war, probably 200,000 Jews passed through the Janowski camp. There were no gas chambers in Janowski—people were mostly shot here. The place of execution was Pisky, or “the sands.” This hilly spot around the camp got its name from the type of soil it had

The Lviv ghetto was officially created in November 1941 and the Lemberg labor camp in early 1942. It was also a plaza for murdering Jews and a transit point from which people from the Klepariv cargo station were sent to the death camps in Bełżec and Sobibór. During the war, probably 200,000 Jews passed through the Janowski camp. There were no gas chambers in Janowski—people were mostly shot here. The place of execution was Pisky, or “the sands.” This hilly spot around the camp got its name from the type of soil it had.

“Tears, tears. This was my people!” says a tanned man of about fifty-five. He’s wearing a white yarmulke with a star of David and holding an Israeli flag in his hands. He is also a part of the column of people in the March of Life. “I’m from Bulgaria. My name is Ivan, or Yohanan in Jewish—it means ‘God is gracious.’ Seven years ago I found out that my Bulgarian grandma Spasa was actually named Sarah. My grandpa didn’t want to change his name, so he stayed Jeremiah. My family never said the word ‘Jew.’ Never,” Ivan is agitated and breathing heavily. “I’m lost for words. Tears, tears.”

The group reaches Pisky. Here dozens of people have already gathered before a small stage. Two men greet each other:

“Did I miss much?”

“No, we gathered near the station, the musicians played ‘Tango of Death,’ and we set off for Pisky.”

“Tango of Death” is a melody that was specially written to be played during executions. One day in Pisky they shot and killed 25,000 Jews. The musicians played the “tango” as usual, put down their instruments, undressed, and went last to the execution pit

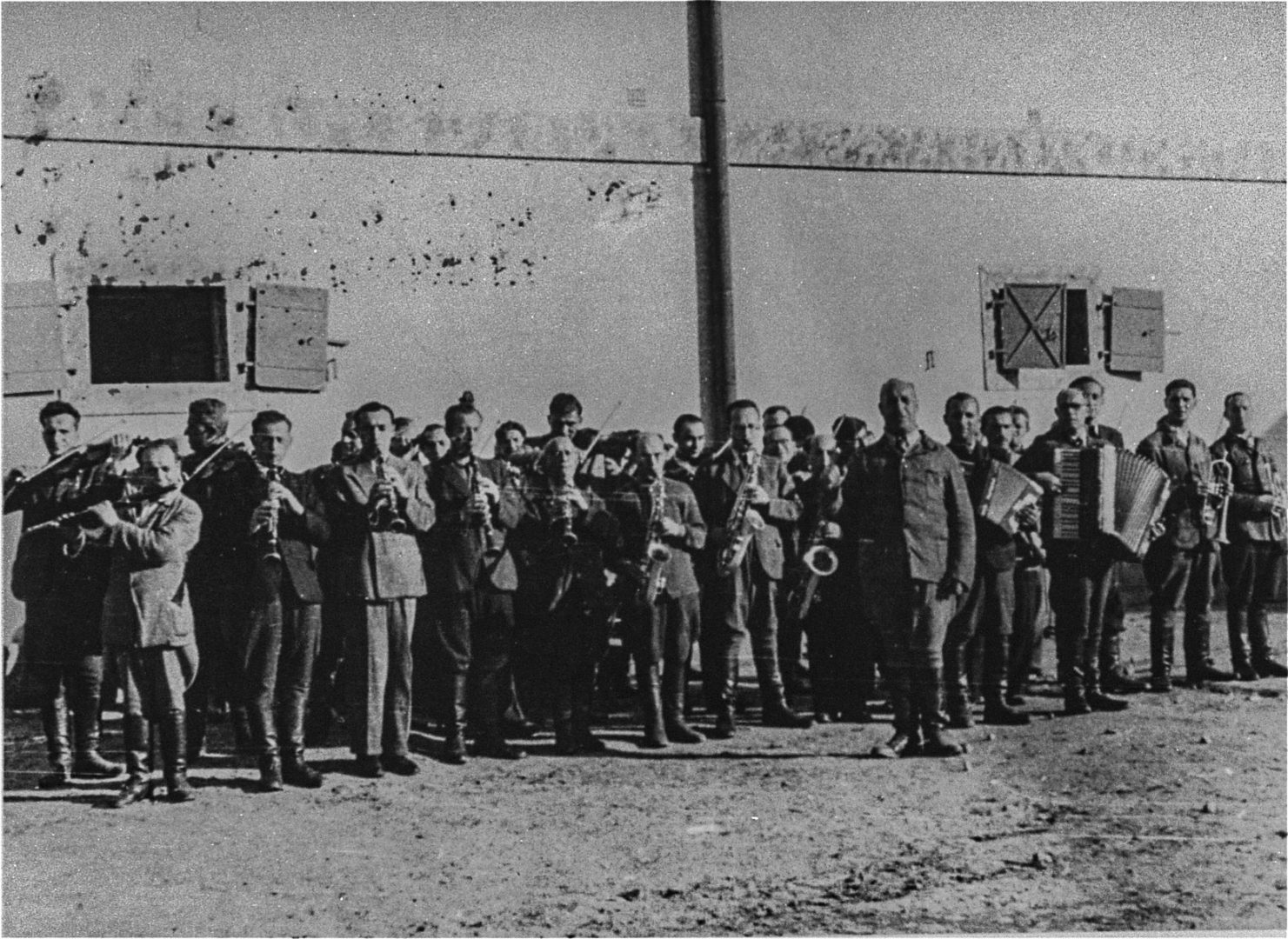

“Tango of Death” is the sadistic invention of Erwin Richard Rokita, the deputy commander of the Janowska camp. Ukrainian historian Oleksandr Pahiria has written about this. Rokita loved music and was a violinist in a jazz orchestra in Katowice. He organized an orchestra of prisoners of the camp—the best musicians and composers in Lviv. It was the Janowska camp’s special calling card. “Tango of Death” is a melody that was specially written to be played during executions. One day in Pisky they shot and killed 25,000 Jews. The musicians played the “tango” as usual, put down their instruments, undressed, and went last to the execution pit.

“The place where we’re standing now has a rather neutral name—Sands,” Andrii Usach, Holocaust scholar, begins the ceremonial part of the March of Life. “But during the German occupation, ‘going to the Sands’ for Jews meant dying. In June 1943, the Red Army was getting closer to Ukraine and the Nazis realized that sooner or later they would have to leave Lviv. So they decided to cover up their crimes. The bodies of the people who were murdered here over the preceding years were dug up and burned, and the ashes scattered. The entire space where we’re now standing became a great grave. Writer Martin Pollack has most accurately named this place the poisoned landscapes.”

The Voice of Blood

“I was invited to the stage as someone who has survived the Holocaust. I was supposed to tell you about those terrible events, but I don’t remember anything about them,” Yurii Stozhynsky, a man wearing a gray yarmulke the color of his hair, speaks to the crowd at the March of Life.

Mr. Stozhynsky was born in the city of Brody in 1941. His father was Ukrainian and his mother was Jewish.

“When I was two years old, my mother died,” he explains. “She went to Lviv, got caught in a raid, and never returned home. My grandpa had a house with an orchard and they hid me there until the city was liberated from Nazis. My father would sometimes tell me about Mom, but I have remembered little. I was raised as a Ukrainian, but after I retired I heard the ‘call of my blood.’ I was curious to learn more about Jews, their history, and religion. I followed in my mother’s footsteps and visited the Bełżec death camp, since the majority of Jews from Lviv and the Lviv region were exterminated there. But in Bełżec I was told that my mother was most likely killed in Sobibór where the Jews who were arrested in Lviv in 1943 ended up.”

Somewhat pedantically, Mr. Yurii offers a few more precise facts: about the gas that was used in the concentration camps—from the Soviet tank T-34, about the duration of the prisoners’ agony—20 minutes, and then he tiredly steps off the stage.

“I’m not much of an expert on Ukrainian history, but when I started getting interested in it, I painfully read a few pages,” Anatolii Havryliuk, a senior bishop with the Association of Independent Charismatic Churches of Ukraine, speaks next. “Before WWII, there were many Jewish pogroms on the territory of Ukraine. A few years ago, a group of Christians and I traveled to nearly 20 cities and towns where Jews had lived and still do. We asked them for forgiveness for the Jewish blood that had been spilled on our earth.”

Pastor Andrii’s face is pale and has no flush. His appears mournful.

“Jews are God’s chosen people. The Bible says, ‘For he that toucheth you, toucheth the apple of his eye.’ Here on our earth, the Jews weren’t simply touched, but destroyed. Many people no longer remember this, but the earth remembers. The word of God says, ‘The voice of thy brother’s blood crieth unto me from the ground.’ It cries not only to God, but also to us. What will we do with this memory? Our earth is defiled; there is a curse upon it from the blood spilled. And it can be purified only through repentance.”

The pastor turns to look at the people sitting in the first rows near the stage. These are the few who remember the Holocaust.

“I represent an association of Christians, who have delegated me to ask you Jews for forgiveness for the fact that the blood of your parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents was spilled in Ukraine. At the hands of not only Nazis, but Ukrainians, too. Please forgive me.”

Pastor Anatolii kneels. An elderly woman is looking intently at him. She turns her eyes full of tears to the sky and then nods her head in affirmation—we forgive…

Sokrushennia

You won’t find the word sokrushennia in ordinary dictionaries, but religious thinkers have much deliberated over it. It means sadness, contrition, the desire to change oneself and one’s life, the breaking of a once stony heart. When the group from Germany takes the stage in Pisky, it is precisely sokrushennia that marks their faces.

“The deportation of 200,000 Jews from the Klepariv station. The sadistic abuse of the workers of the Janowski camp. The terrible executions here in Pisky. This was us!” Hans Reuß, the international director of March of Life, speaks clearly and with restraint. “This was our grandfathers—soldiers and officers in the SS and Wehrmacht. They brought this horror to Lviv. We stand here today to find the words that they never spoke. We want to ask forgiveness for what we caused the Ukrainian people. We want to ask forgiveness for what we caused the Jewish people. We called many Ukrainians to assist in our crimes. It was often forced, but sometimes also voluntary. As Germans, we can only bow before you and ask for forgiveness.”

After Hans, twenty-year-old Kim, whose four great-grandfathers were all in the SS, one of them in Ukraine, asks for forgiveness. Then blue-eyed Matthias who only found out a month ago that his great-grandfather was involved in the Holocaust. Then fifty-year-old Michael, the grandson of Karl who was a Nazi, a guard at the camp in Lviv, and never in his life regretted it.

The slight Kim takes a violin and begins to play an unknown tune. In the area of Pisky all melodies begin to sound like “Tango of Death.” The group from Germany is now giving dark red roses to the Jews present at the March of Life. Matthias, the boy who looks like an SS soldier, goes up to Yohanan, who has been called Ivan his whole life. They hug for a long time. Their faces are not visible. Only by the shuddering of their shoulders can you tell they are crying.

“You Didn’t Serve God with Joy!”

“Shalom, friends!” a man in a tall black hat greets the crowd. This is Mordechai Shlomo Bold, the chief rabbi of Lviv. “The Torah says, ‘All of life’s curses are caused by one thing—for you did not rejoice in life, you didn’t serve God with joy!’ This is an obligation that is also written about in the Bible—to be a joyful person. For can you imagine a person who gets up in the morning, looks out the window, and says, ‘What a beautiful day!’ and then goes and kills ten thousand Jews?”

The sun gradually sets over Pisky. A choir of crickets seems to accompany the rabbi.

“The bodies of those who were killed in Pisky or the Janowski camp were destroyed, but their souls live on!” he expressively continues. “They are here with us. Let us celebrate life! And then the Holocaust will never be repeated.”

Rabbi Mordechai goes quiet and then begins to hypnotically sing the Kaddish, a memorial prayer. A few minutes later, another rabii, Siva Fainerman, translates it into Ukrainian:

“Lord, full of mercy,” he reads in his elderly voice, “defender of widows and father of orphans, we pray to thee who art in heaven, under cover of thy presence grant true rest to the souls of the millions of sons and daughters of your people: the men, women, and children who were shot, slaughtered, burned, suffocated, and buried alive. Among them were the righteous and geniuses, pillars of scholarship, experts on the Torah, and simple people. They were all pure and holy, for each of them died in thy holy name. Their blood will not go into the earth without a trace, their dying prayer will not go unanswered, thanks to their righteousness, the exiled will gather in the land of their forebears, for they are the holy martyrs of Israel and always stand before the face of the Almighty, in him they receive eternal rest. We say together: Amen!”

When I was standing there in Dachau, I could feel my heart fall and break into six million pieces. And then I saw the hand of God picking up those pieces, putting my heart together, and giving it back to me

Her Heart is Breaking

Rose Price survived six concentration camps. When she was 16, she was liberated from the camp at Dachau. She was an honorary guest at the first March of Life in Germany. That year was the first time Rose had returned to the concentration camp since her liberation. When the descendents of the Germans and the Holocaust survivors sang the Memorial Kaddish, Rose became hysterical—she shouted and wept loudly. Yet after a while Rose asked the organizers of March of Life to let her speak. They were confused. But when this nearly eighty-year-old woman began to speak, she shone. They later asked her what had happened. She said, “When I was standing there in Dachau, I could feel my heart fall and break into six million pieces. And then I saw the hand of God picking up those pieces, putting my heart together, and giving it back to me.”

“This is what the March of Life is,” Hans Reuß says. “We stand helplessly before the devastation of our history, but God is right beside us. He looks upon us and heals.”

We are grateful to the Territory of Terror Memorial Museum of Totalitarian Regimes for giving us these archival photographs and identifying them:

1. Place of mass execution of prisoners from the Janowski labor camp, the so-called “Valley of Death,” 1944. Source: State Archive of Lviv Oblast

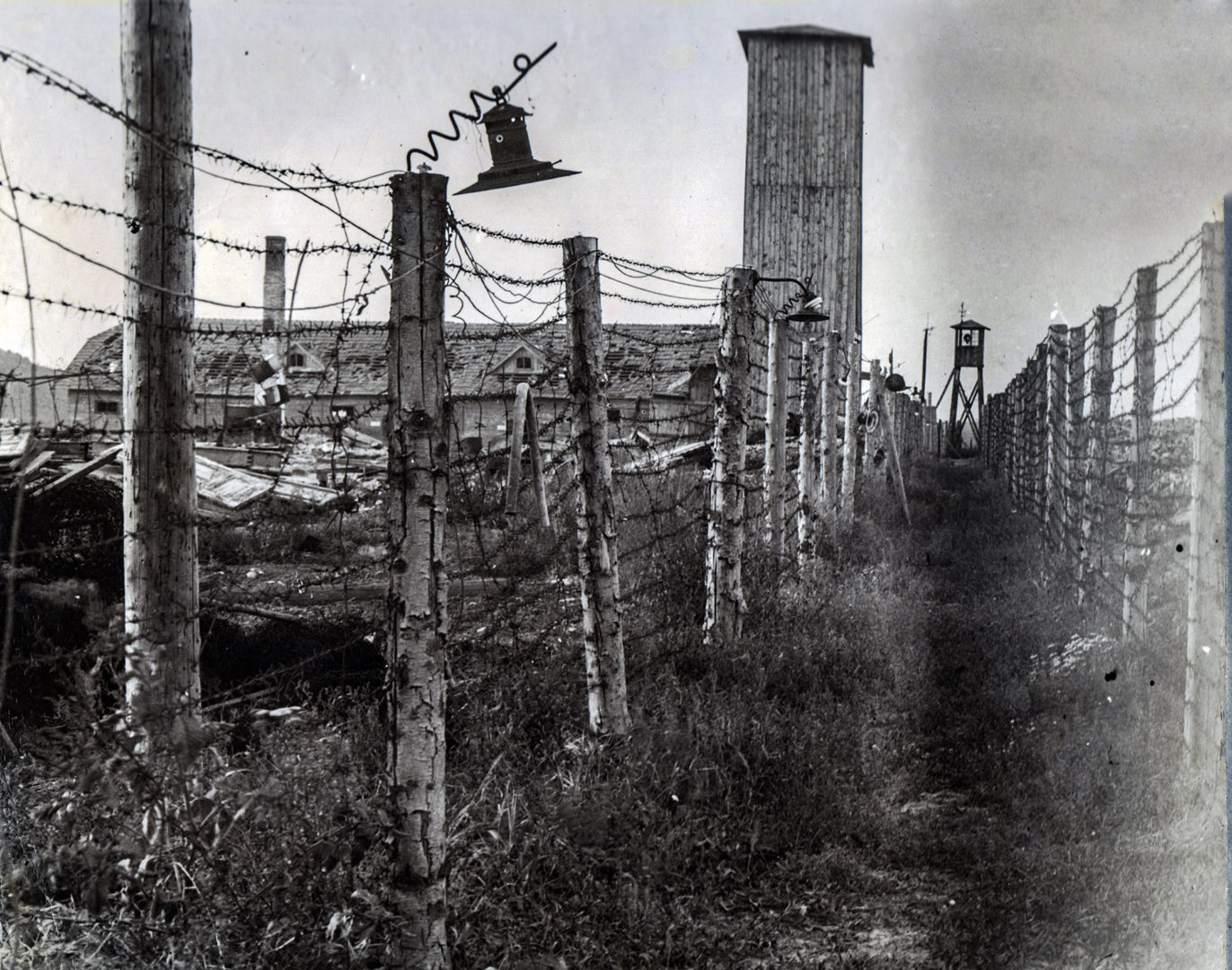

2. Barbed-wire fence at Janowski labor camp, 1944. Source: State Archive of Lviv Oblast

3-4. Orchestra at Janowski labor camp. Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

5. Shoes found at Janowski labor camp, 1944. Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

6. Belongings found at Janowski labor camp, 1944. Source: State Archive of Lviv Oblast

7-8. Scene of a Jewish pogrom not far from the prison on Łącki Street, July 1, 1941. Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

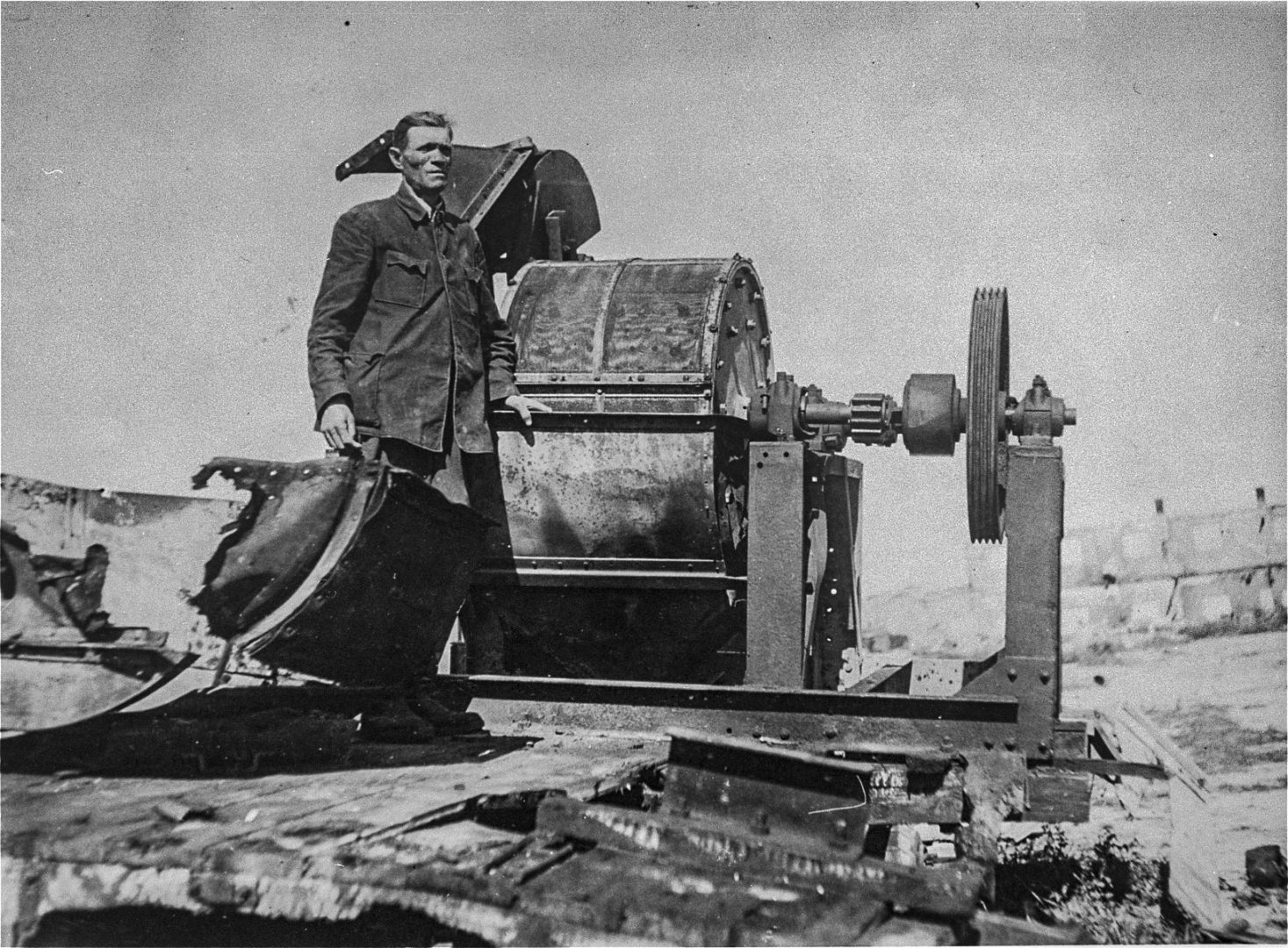

9. Former prisoner Moisei Korn, member of the so-called “death brigade”, 1944. Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Translated by Ali Kinsella.

[This publication was created with support of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Norwegian government].

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More