The Favorite Toy

“I’m a tractor driver slash artilleryman,” Mykola says—this is the way he’s been typically describing himself. “But now I’m also an owner of a preschool.”

We enter the hallway of a preschool in one of Kyiv’s residential neighborhoods and take off our shoes. Cubbies are lined up against the walls, some of them with photos of children so they know which one is theirs.

Mykola walks down the hallway with its colorful walls, making his way among the toys flooded with March sunlight, small tables and chairs, and teepees. It feels like a fairy-tale land where Mykola and I are giants.

“Do you have any chairs for adults?” I ask, joking.

“Of course not, it’s a preschool for children,” he says, joking back.

Mykola enjoys coming here. Sometimes, he can hardly believe it has actually taken off. While preparing for the opening, he continued coaching veterans for the U.S. Air Force Trials [an annual Paralympic-style competitive event for veterans — Ed.] in the mornings and spent his evenings fixing what remained to be fixed and finishing painting walls, often staying until late at night. The once bare walls began to bloom with colors.

A tractor driver and a mortar

Before enlisting, Mykola Zaritskyi worked in agriculture—hence his nickname “tractor driver.” He was first mobilized in 2015 when Russia had already started war in eastern Ukraine. Zaritskyi served as a border guard in Sumy Oblast.

His hometown is Bilopillia in Sumy Oblast, less than ten kilometers away from the Russian border. Currently, Russians pound this town and its residents with guided bombs on a daily basis.

On the morning of February 24, 2022, Russian troops invaded Sumy Oblast and headed towards Buryn along the Konotop highway. The next day, fighting started in the vicinity of Okhtyrka and Trostianets. Russians set up checkpoints in Buryn and Sofiivka, while Bilopillia became a kind of wedge between these two villages and the advancing Russian forces.

Zaritskyi evacuated his wife and daughter, who was not even a year old at the time, from their apartment to his parents’ house in the suburbs, thinking it was safer there. He himself decided to return to the army. He joined the patrol in Bilopillia for a while and was then sent for training in Lviv. Zaritskyi was supposed to be trained as an artilleryman.

In May, his brigade was holding the line outside Lysychansk in Luhansk Oblast. After the Russians occupied Sieverodonetsk and began encircling Lysychansk, the Ukrainian army was forced to retreat. In June 2022, Luhansk Oblast was occupied. Zaritskyi’s unit was then dispatched to Kherson Oblast, and Zaritskyi himself was assigned to the mortar squad.

“I argued with them because using a mortar didn’t seem quite reasonable. The distances were too large, and I simply couldn’t reach them,” Zaritskyi admits. “But we did whatever we could.”

One day, he didn’t notice an anti-personnel landmine hidden under the fallen leaves. In early October 2022, his squad was crossing the Inhulets River to seize former Russian trenches, with Zaritskyi tasked with scouting the area. In a fleeting moment, as he took step after step, listening for incoming and outgoing rounds in the distance, he assumed that a shell had landed nearby. He felt his left leg going numb, then a hot, burning sensation.

“I looked down and thought, ‘That’s it. The war is over for me,’” says Zaritskyi.

At the hospital in Odesa, he learned that another four soldiers had been blown up on landmines in the very same forest on the same day. And all of them had lost a left leg—later, they’d all laugh at it. After the incident, the war was not over for him, but his military service was. What followed were surgeries, reamputation, and obtaining a prosthesis in the United States.

Zaritskyi took his first steps with a prosthetic leg in January 2023. It hurt a lot, but today, if people don’t know about it beforehand, they might never even notice he has one.

So Diverse

Zaritskyi was inspired by his daughter, Sofiia.

He came up with the idea of starting a preschool while training for the Invictus Games. During those days, he was contemplating starting a new business. He had sold his tractor, and half of the fields in his region had been mined. He’d also been discharged from military service due to his health condition. And yet, this man couldn’t simply sit idle. He also found that immersing yourself in work helped stave off thoughts about war. Right then, he discovered that the Ukrainian Veterans Foundation was offering grants to veterans to start new businesses or expand existing ones. Initially, he considered opening the school in Sumy, but then decided on the capital city, as he had a good friend there who had experience in running such a business.

Maryna Kharlamova, a preschool teacher and psychologist, had experience managing preschools including designing programs for adaptation and emotional intelligence development. Zaritskyi was confident that she would make an excellent partner and director for his new center.

The preschool opened on March 3, 2024, eighteen months after Zaritskyi lost his leg. However, he was on a different continent when they welcomed children for the first time. He was en route to Las Vegas for the U.S. Air Force Trials, accompanying a Ukrainian team of veterans and soldiers as an assistant coach. This was another important mission for him.

Zaritskyi became an assistant coach after participating in the Invictus Games, an international adaptive sports competition for wounded warriors and veterans, held in Dusseldorf last September. He had loved sports since school, engaging in track and field athletics and becoming a six-time champion among adolescents. So, there was no way he could give up sports even after losing a limb. Even though the Invictus Games are primarily about rehabilitation rather than competition for medals, Zaritskyi fought for his: two gold and two silver.

At the opening of the school, Zaritskyi’s pant leg got slightly pulled up, revealing his prosthesis. One girl saw it—perhaps for the first time in her life—and tugged at her mother’s sleeve in curious surprise.

“Look, mama! It’s a robot!”

The girl’s mother didn’t know how to respond to that and simply shushed her. Zaritskyi doesn’t get emotional about incidents like this; it’s just children being spontaneous. The reaction of adults is a different matter, though.

It’s also one of the reasons he opened a childcare center. The curriculum is designed to expose children from the youngest age to the diversity of the world around them as a norm. And then, perhaps, this generation will teach tolerance to their parents who didn’t discuss it with them when they were young.

At first, Mykola came up with the name “Sonia Kids” for the preschool but eventually opted for “So Diverse.” It just better reflects the concept of this school. The idea behind it is celebrating diversity, and they even designed inclusive toys for children aged four and up. Soon, Barbies in wheelchairs, with braces or glasses, and other similar toys will line up on the shelves.

Sad eyes, big ears, long legs

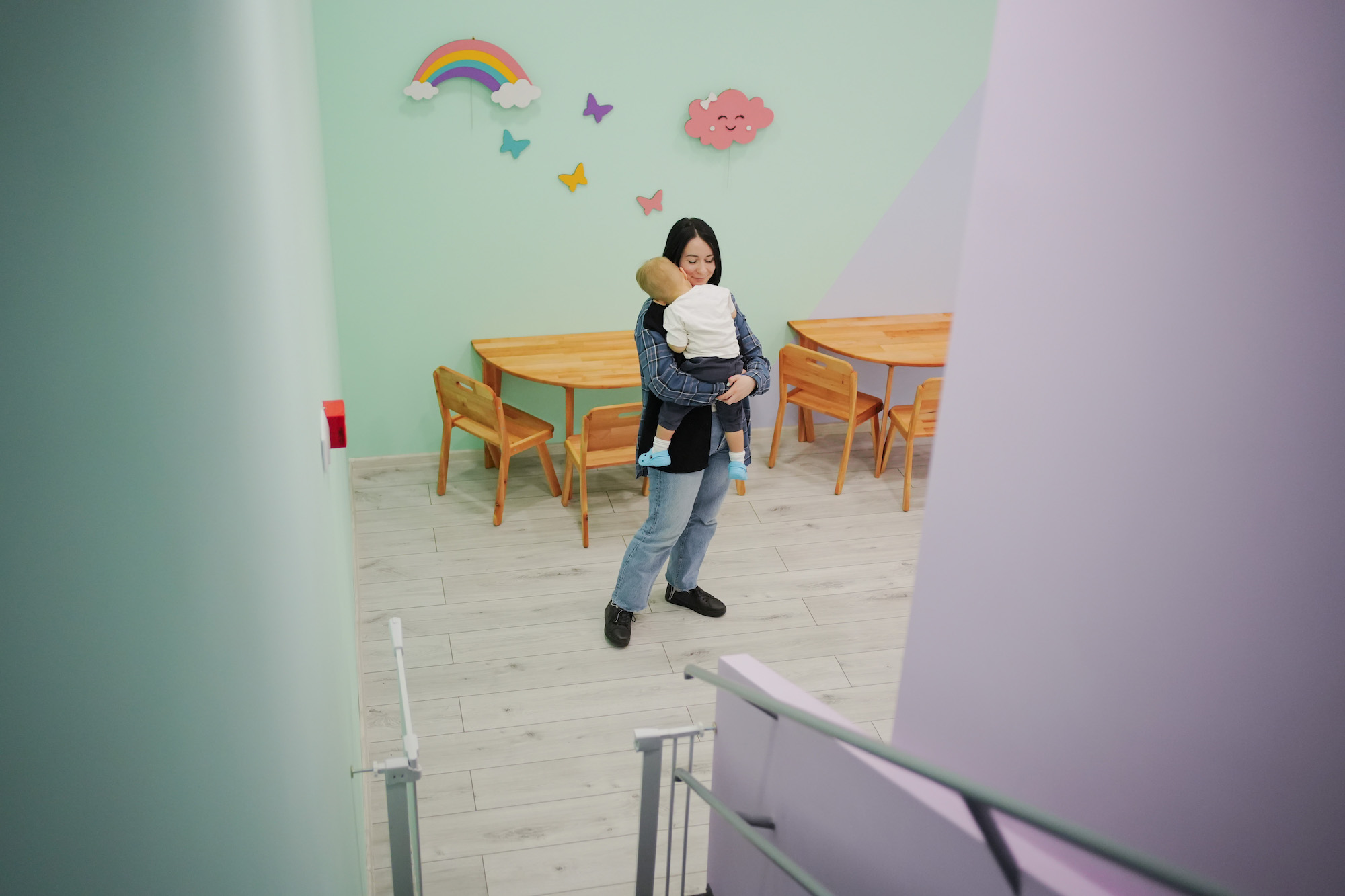

A group of kids are playing while a little girl at the door cries her heart out in her mother’s arms. Her mother promises she’ll be back soon with a chocolate bar and a bunch of balloons. She herself is almost bursting into tears, but she needs to teach her daughter to stay with other kids at the So Diverse and not feel scared without her mother.

The girl won’t calm down. Then, the principal, Maryna Kharlamova, picks her up while her mother slips out the door. The girl is crying and trying to wiggle out of her arms, but Kharlamova whispers something to her gently, and a few minutes later, she does settle down and agrees to go paint and watch cartoons with the other kids.

“It’s important to give her these few minutes,” Kharlamova explains, “but also to reassure her that her parents love her and will definitely come pick her up. Sometimes, parents also need to adapt—to learn to let their children go. Some mothers would cry or look through the window, which doesn’t do any good. Seeing their mother outside, the child cannot focus on anything else and only thinks about her standing there. Dealing with kids is easy and fun. It’s much harder to deal with their parents.”

Kharlamova believes that tantrums signal that children are growing up.

“How would kids learn self-control or how to express their anger if you forbid them to throw tantrums or cry or if you just brush them off, saying they’ll ‘cry it out,’ or even scold them for crying?” she says.

Children learn to identify their emotions. In “So Diverse,” everyone can cry or feel what they feel. They teach kids to prepare birthday gifts and help them realize that “you have the right not to share your toy, but remember that others also have the right not to share their toys with you.” If one kid hits another one, they don’t scold them but explain how that other child feels. In this way, teachers develop the ability to share, empathize, and understand consequences.

The clamor in the hallway is getting louder.

“Are they crying or laughing?” I ask, struggling to identify children’s emotions in the noise.

“Some cry, some laugh,” Kharlamova says with a smile.

Soft, colorful balls and feathers are scattered around the table. A popular turtle song is playing in the background. Each of the four kids sitting at the table is busy doing something different: one plays, another gazes at us with curiosity, while yet another tries to catch bubbles the teacher is blowing.

So Diverse offers choreography and English language classes. Kids also plant microgreens and study the structure of the eye. All toys are eco-friendly, with less plastic and paint. In addition to the Barbies in wheelchairs or with braces that will soon arrive, the preschool has Hibuki dogs or hug dogs—a therapeutic toy designed to help cope with trauma. This method, invented in Israel to work with children’s trauma, is now used in Ukraine, where children also suffer from war. The Hibuki dog has sad eyes that understand the child’s emotional state, big ears to wipe their tears, and long legs to offer comforting hugs.

Zaritskyi looks around, satisfied with his work. He’s happy to see the things rolling and parents bringing their kids to his preschool.

He jokes that he would hardly make it as a teacher because “sometimes, you don’t know how to talk to your own kid.” That said, he worked as a camp counselor once with the youngest groups, so, in fact, he can easily connect with children.

Zaritskyi and I sit on chairs by the entrance to the So Diverse. Warm days in March encourage sunbathing.

“What’s next for you?” I wonder.

“I dream of the war being over and finally chilling. I haven’t burned out or gotten tired. It still pulls me back. My home is in turmoil: it’s close to the Russian border, the shelling only intensifies, and all my relatives live in Bilopillia [A small city in northeastern Ukraine about 10 kilometers from the border with Russia — Ed.] When I’m working on projects or in the preschool, when I’m on the move, it helps me take my mind off this and switch to other things. But I’m not fed up with fighting yet. I would return to the army.”

“Have you got a favorite toy?” I ask.

“Sure. An aiming circle for mortars.”

“The Power to Continue” is a collaborative project between the United Nations Development Programme in Ukraine and Reporters. Our goal is to share unique stories of veterans and civilians who have lost limbs in Russia’s war against Ukraine, and not only found the strength to survive the trauma but also became drivers behind social projects and bold business ideas. We also highlight the stories of people who have helped them along the way. While there are not many of them, these people inspire and speak openly about their experiences, and this might become a starting point for others.

The special project was initiated by Reporters with the assistance of UNDP in Ukraine and financial support from the European Union as part of the “EU4Recovery—Empowering Communities in Ukraine” project. The opinions, recommendations, assessments, and conclusions expressed in these materials do not necessarily reflect the official position of UNDP, the EU, or their partners.

No opponent in the world daunts them. They remove their prosthetics and charge forward to seize victory

For the past eight years, a small family business run by an ambitious engineer has been transforming pieces of metal into components for new prosthetic limbs

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More