Seven Kilometers of Memory

he sectoral state archive of the Security Services of Ukraine (SBU) is the largest open archive of a repressive government organ in the world. There are 224,000 files on its shelves. When access to KGB documents was granted in 2015, the archive was barraged with thousands of appeals. Journalists, relatives of the repressed and executed, and people whom the KGB had open files on themselves all wrote in. As well as those who were demanding the lustration of the government.

Over the last three years, the archive has been headed by historian and civil activist, Andrii Kohut. He’s not yet forty, but he’s already workED at the Reanimation Package of Reforms, the Center for the Study of the Liberation Movement, the International Renaissance Foundation, and founded the civil network OPORA. Thanks to the laws that Andrii and his colleagues worked on developing, decommunization is taking place in Ukraine.

We learned how the archive works, how to find the necessary folder from among the sea of documents, and what might impress someone who has seen lists of thousands of the executed.

Neighboring Victims and Executioners

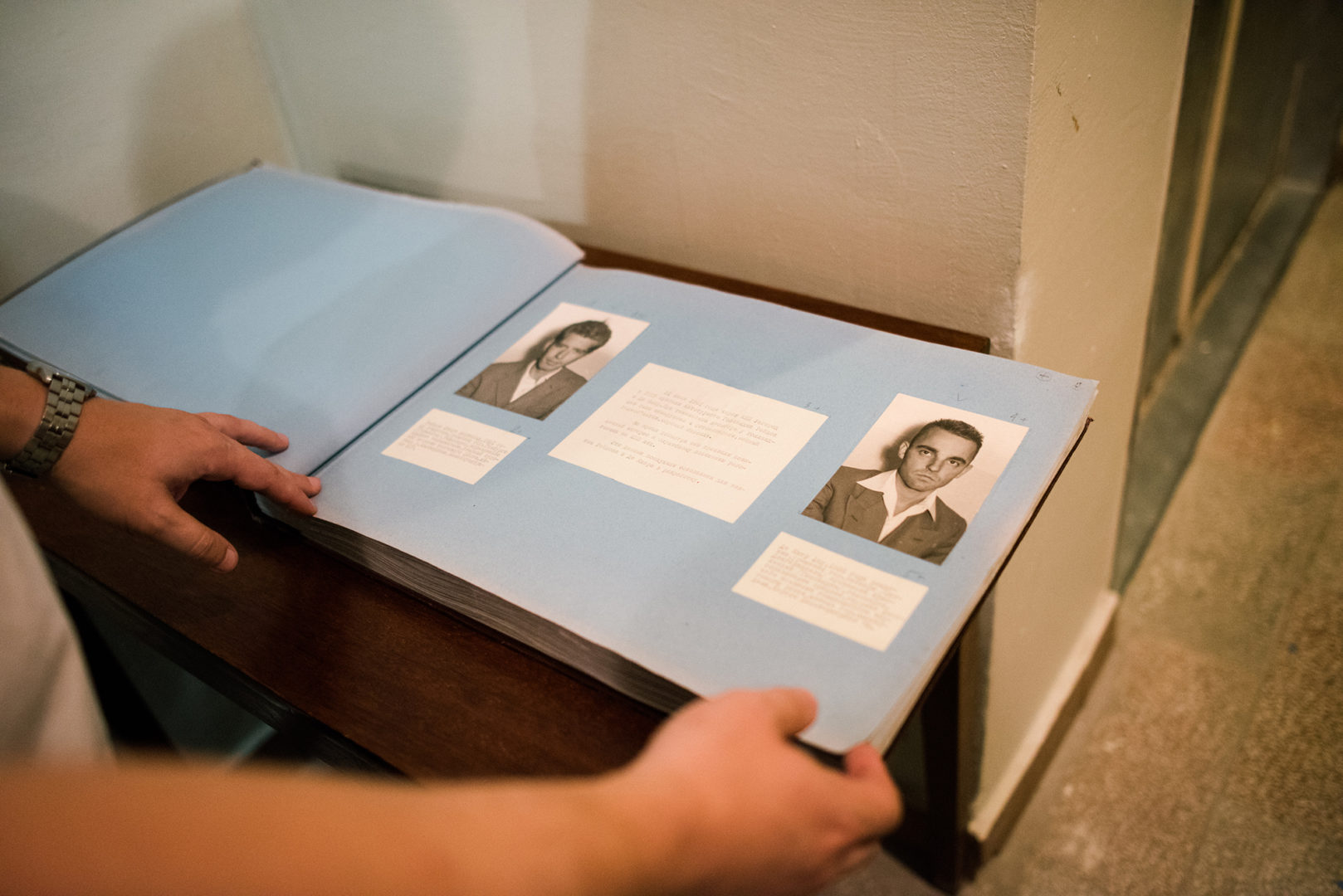

Oleksandr Fedorovych had a bald spot, sharply angled brows, and a dimple in his chin. Oleksii first saw him in the office of Andrii Kohut, director of the SBU archive. Oleksandr Fedorovych is his great-grandfather.

They ended up at the SBU archive for different reasons. Oleksii was shooting a social film about access to Soviet special forces documents; Oleksandr Fedorovych was staring at his great-grandson from a photograph in his personal file. During his life, he worked at SMERSH, one of the cruelest repressive organs in the USSR that, according to some sources, killed millions of civilians under the slogan of the fight against spying.

“I was sitting in the office getting ready to shoot and I remembered that Grandma had once told me about her father, who worked for the KGB. I called her, found out his name and date of birth. In 20 minutes they brought me my great-grandpa’s folder.”

Oleksii had never even seen his photo, and his grandma hadn’t told him very much. Her parents got divorced yet before the war. She didn’t meet her father until she was in university. In the 1980s she got a death notice and cried.

Oleksandr Fedorovych was poorly educated: he graduated from the forest technicum and worked as an engineer, then at a Soviet club in charge of propaganda and agitation. He ended up working for the NKVD (the predecessor to the KGB) as a young investigator in 1940. At first he worked in Vologda region, during the war he was transferred to Kharkiv, and later to Kyiv.

Besides an inventory of his professional achievements, the folder contains references from Oleksandr Fedorovych’s higher-ups. In the first of them, the newly baked investigator is described as “energetic and insistent.” He “quickly learns the methods of an agent and takes cases independently, but he’s undereducated, needs the help of his older comrades, and makes mistakes during interrogations.”

“I think that at first he didn’t quite accept the methods of the system he had landed in,” Oleksii says. “I don’t know what happened there, but the word ‘interrogation’ paints a terrible picture in my imagination.”

Four years later, Oleksandr Fedorovych had changed: “he knows the agent investigator process well,” independently conducts complex group cases, has completed 26 cases on 54 people since he’d started working. Of them, seven were on enemy intelligence and counterintelligence agents, “personally discovered three agents and led four cases against eight members of a counterrevolutionary organization of Ukrainian nationalists.” No one escaped his investigation; he was “insistent and principled in his work.”

“What scares me most is this change in four years—this illiterate club manager has suddenly learned how to do everything and is uncovering Ukrainian nationalists.”

Oleksii didn’t tell his grandma about what he found in the archive—he didn’t want to make her sad. Oleksii rarely talks about his great-grandfather who was in SMERSH, which repressed Ukrainian nationalists, organized secret meetings, and recruited others

Oleksii compares this to the present day: the political prisoner Murad Aliev has said that the workers in the colony initially did not employ torture, but later they were “taught” and then they initiated torture on their own.

It seems to Oleksii that after the war, something in his great-grandfather’s psyche snapped. The references are mostly positive: he was leading a case against the OUN underground, but some strange denunciations, letters, and complaints: he couldn’t share his apartment with his inferior, he treated the garrison boss’s wife rudely, he was given a 15-day suspension. And finally in one of the last references, Senior Operations Officer Oleksandr Fedorovych was irresponsible about his work, fooling around, not taking on cases, not writing denunciations.

Oleksii didn’t tell his grandma about what he found in the archive—he didn’t want to make her sad. Besides him, no one saw the file—his family decided to remain in Luhansk because they support the LNR. Oleksii rarely talks about his great-grandfather who was in SMERSH, which repressed Ukrainian nationalists, organized secret meetings, and recruited others.

“I went out to the balcony to smoke and I was looking at passers-by and thinking that the grandson of an executioner can walk down the same street as the grandson of a victim. we need to know both the victims and the executioners. We all live in this soup and we need to deal with it. We need to know our history, not invent it.

To Have and to Hold

The repository where Oleksii shot his film, holds the fifth and sixth collections. This repository is the only one open to journalists. Almost at random, Andrii Kohut takes a thick folder from the sixth collection off the shelf and immediately comes across something interesting: Roman, a forcibly resettled person from a border region, was shot in 1934 because he received “help from Hitler.” Behind it is a story of an entire German national minority that was resettled on the territory of Ukraine in the 18th century. During the 1932–1933 Holodomor, its members tried to get aid through the German consulate. German priests wrote abroad about the famine and distributed the aid they received (mostly money) among the famine sufferers. Later those priests were shot.

Reams of files lie on hundreds of shelves in the six repositories of the SBU archives at 7 Zolotovoritska St. The building was built especially for the archive in the 1990s. The structure is equipped with special ventilation and control sensors: documents are usually comfortable at 64.5ºF and 70% humidity. There are rooms with the compact shelving that saves space and allows for more cases to be held. But the majority are outfitted like at the end of the last century.

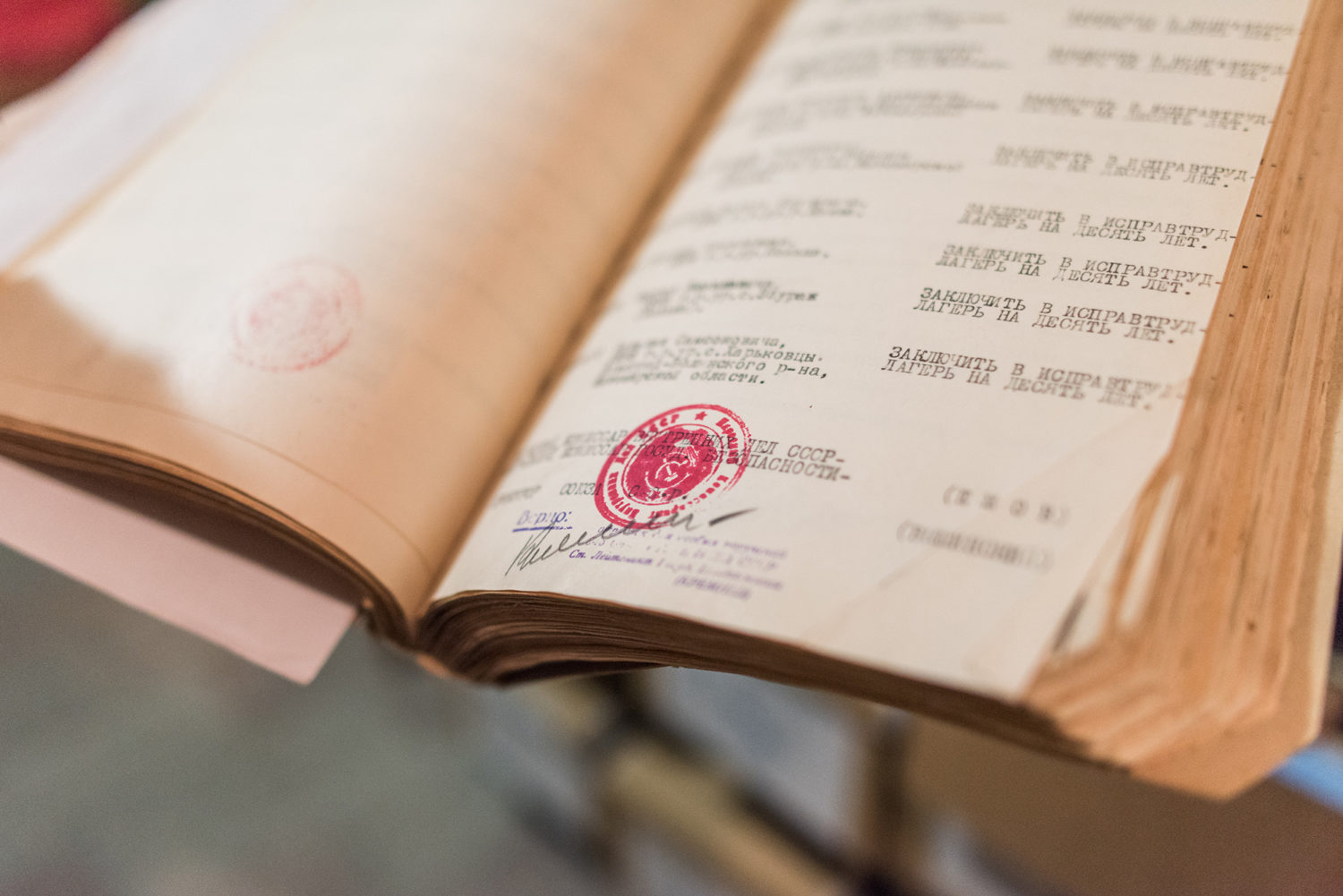

In general, the archive has 80 collections that are constantly being arranged . The fifth and sixth collections are the archival criminal cases of the unrehabilitated and rehabilitated, respectively. In addition, the sixth collection contains the execution protocol for the “twos” and “threes” (organs that passed extrajudicial sentences). The signature of the People’s Commissar for State Security and USSR Narkom of Internal Affairs, Nikolai Yezhov. But, Kohut explains, Yezhov never read the cases—with his signature he immediately doomed you to execution, just like on a conveyor. There are lists of hundreds of last names with a single verdict next to them; there are also large-format files where the reason is indicated.

You can’t just carry any old case into the reading room—you must have a declaration signed by the director, a description of the documents, and the reader’s signature. If it turns out that the case is at all damaged, it is sent for restoration.

The Reliable Donetsk Rear

The SBU archive is not only the repository in Kyiv. There are temporary holdings archives in every regional capital under SBU administration. As a rule, these are archival-criminal cases and cases on the workers of those very archives under the Soviet Union.

Access to the archives in the Crimea, Donetsk, and Luhansk regions is effectively lost for now. No one can say for sure, but there is information that the files in Crimea are still being kept. As for Luhansk, nothing is known. Ukrainian prisoners of war have told stories about the Donetsk archive: once they all slept on the bare shelves in the repositories—the files were either destroyed or taken by the “humanitarian convoy.” Requests for Donetsk folders come every week, but there’s nothing to tell those people.

“No one was ready for that,” explains Kohut. “The feeling of a military threat remained as part of the legacy of the USSR. The enemy is in the West; NATO poses a threat. It seemed like the ‘separatist’ moods could come out of Western Ukraine, closer to Europe, and that the Donbas was the reinforced concrete region that will always be calm. The Donetsk archive was ‘deep in the rear’ and considered the safest.”

Because of this certainty, nothing was taken out of Donetsk: orders, instructions, protocol, and other valuable files remained in one of the largest temporary holdings archives. Among the losses are the documents from the 1930s, a time of industrialization of the region, and the unique cases from the “Greek operation”—a national campaign to destroy the Greek community during the Great Terror.

Looking for the Paper Trail

One time, a Lviv professor went to the archive in order to get his own file—it had been opened during his overly stormy student years. The professor was assured that the file did not exist, but he decided to go and talk to Andrii personally. It turned out that there was in fact a file, but that it was part of a group and they found it under the last names of other people. But the professor still couldn’t get it. The file coded “Plesen” had been destroyed, likely still under the KGB. What happened in his youth, now one would not know.

“The files are rarely sensational,” Kohut notes. “As a rule, it’s a dry list of facts and events whose context has to be understood. Expectations for the quests are not always met. Family stories are one thing, but having the documents in your hand is another.”

In the last six months, the archive has received 1800 requests. Most often it’s people looking for their relatives. Sometimes it’s grandchildren or great-grandchildren who might never have seen the people they’re asking about. In these cases, the KGB documents are the only opportunity to find out who their grandmas or grandpas were.

Irrespective of which file you’re looking for, it is best to start your search online. For example, the archive for the Center for the Study of the Liberation Movement includes the databases Rehabilitated Stories, Open List, and Moscow’s Memorial. If the necessary person is found among these databases, it is likely that the file is located in one of the archives.

If a relative was repressed or kept under observation, her file is located at the SBU archive. Documents regarding deportation or exile are kept in the archive at the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVS). A portion of the files was transferred to other state archives. So for a successful search, Kohut recommends writing multiple letters from the start.

The SBU archive website offers a sample request. The minimum information needed to search is first name, patronymic, last name, date and place of birth, and circumstances of repression. Then there are a few options: personally travel to the archive to see the file, order it from a different region, or get digital copies. All requests are supposed to be answered within a month.

It is also possible to fail. The USSR went through a few waves of destroying files. The first took place right after Stalin’s death. There was often compromising material in files on party members themselves, so the documents were destroyed in order to “not sully the honest names of Communists.”

The last time “documents were put in order” was in the late 1980s–early 1990s. During perestroika KGB agents realized that their opponents could come to power, so they decided to literally start life from a clean sheet. Consequently, it is sometimes easier to reconstruct events of the Great Terror than the more recent 1980s.

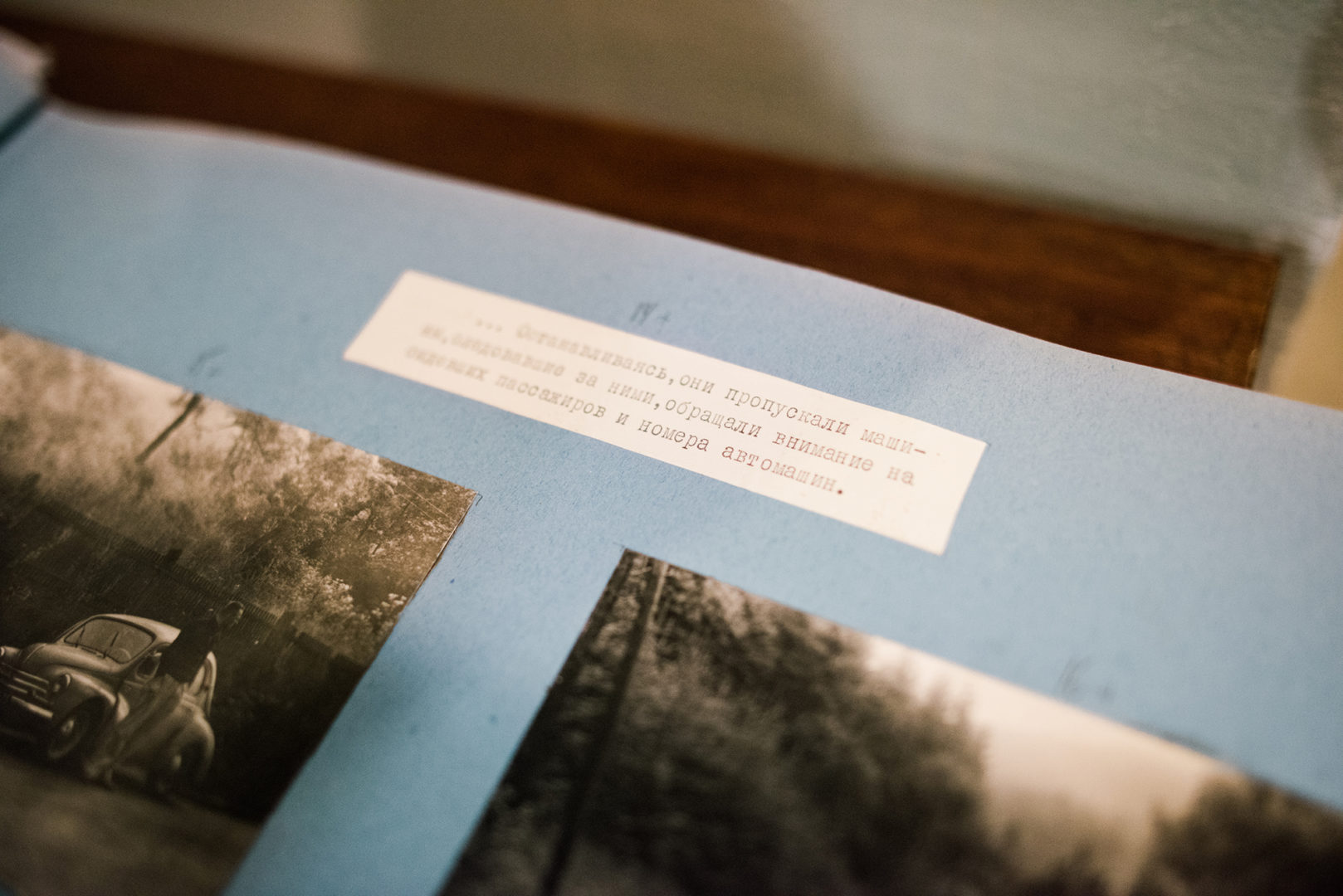

But some information can even be gotten from the destroyed files. The sixth collection holds extracts from the interception and censorship correspondence, even if the files belonging to the letters’ authors were destroyed. The KGB reported on the mood in society, using citations from letters for this. They also recorded society’s reaction to harvests and the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU’s speech at each of the party congresses.

Kilometers of Prohibitions

The archives can be measured in different ways: we in Ukraine count the individual units they contained, but in Europe they’re measured by the kilometer. Under the first system, the SBU archive holds 240,000 pieces, either files or separate volumes. By European measures—7 kilometers

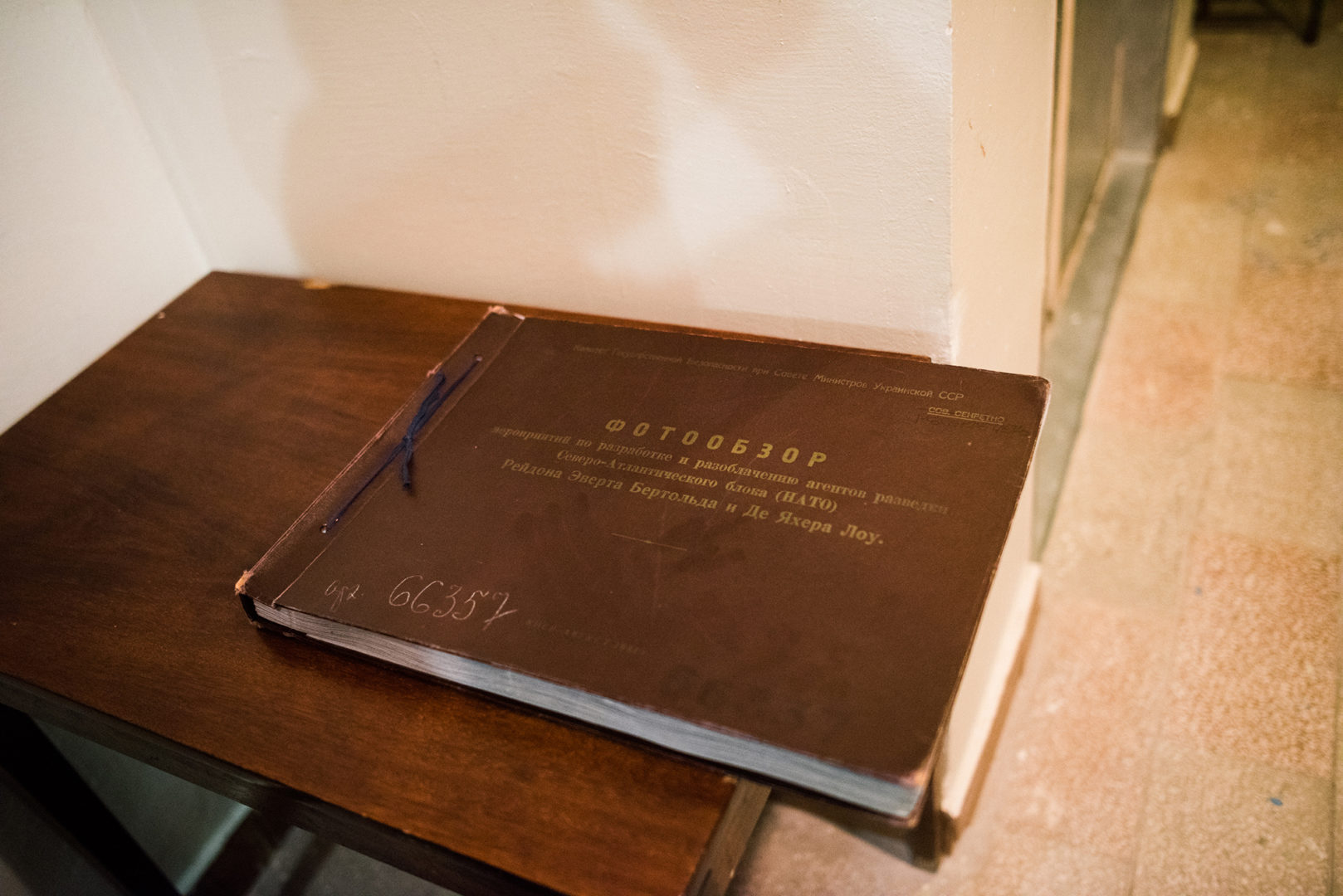

“This is the most open archive of repressive authorities in the world,” Kohut explains. “The key word here is ‘open’: under Ukrainian law, archival documents are not a part of private information. Anyone can gain access to them. Our approach is different from Europe’s.”

The Stasi archive in Germany contains 111 kilometers of documents, but it’s not so simple to get to them. Half of the files are on Stasi agents themselves. The situation is unique since files like that are not usually kept. When the merger of East and West Germany began, demonstrators seized the Stasi building and the workers didn’t have a chance to destroy the documents. Actually, Germany did not merge, rather East Germany joined West and the archive came under the jurisdiction of Western European legislation—if a file contains the surnames of people who have no relation to the requester, they must be redacted. Crossing out names in the copies can take a few months, so some people have to wait years for an answer.

Game in Repression

“They asked how many Americans had approached me under the article on historical truth,” thus SBU workers interrogated Ruslana Zabily, the director of the Lviv museum Prison on Lontsky Street. It was March 8, 2010. In order to understand just how access to the documents of repressive organs was granted, it is necessary to turn to precisely this episode.

Zabily was writing a dissertation, “Particularities of the Armed UPA Conflict,” about the insurgents’ strategy, tactics, and operative arts. The scholar had gone to Kyiv for a few weeks to work in the archives. He had just gotten off the train when six men approached him, introduced themselves as employees of the SBU, showed him their badges, and asked him to go with them for a conversation with Valerii Khoroshkovsky, then the head of the Service.

“They took me under the arms, stuffed me into the back seat of their car, and forbade me from making any phone calls,” Ruslan recalls. “We entered the SBU building on Volodymyrska Street not through the main entrance, but up the fire stairs. In reality this was not an invitation to a conversation, but a unlawful detention.”

Ruslan worked with documents from archives, including the SBU’s and private collections. The process of declassification had not yet then been completed, but the documents that had already gone through it were available for viewing. In the words of the SBU director, someone copied documents from their archive that were stamped “top secret.” They suspected Ruslan might have them and interrogated the historian from 8 am to 9 pm. They were planning on checking twenty more of his colleagues. It later came out that the then SBU’s complaints were in regards to the lists of the executed that hung on banners in the museum. They were missing the “declassified” stamp—it appeared only on the file and not on the individual documents, so there was in fact no violation. The banners are still in place.

Zabily says that really they weren’t looking for the documents, but scaring historians. In 2010 the SBU carefully guarded Soviet secrecy. Ruslan was asked who his academic supervisor was, whom he had consulted with, and what contacts he had abroad. They attempted to persuade him to give up academia and teach history in school. Ruslan was threatened with eight years in jail for “collecting information that contained state secrets with the intent of sharing it with third parties,”—in other words, for spying.

“Of course I was scared. Especially when the threatened to take away my ID and call the police so they could deal with me like an ‘undocumented person who has illegally entered a restricted object.’ Everyone knows how the police ‘work’—in three days they would have beaten any and all confessions out of me.”

However the scholar knew that it would not likely come to that, so he did not back down and did not surrender his devices. Even though they had promised to return it in the morning, in a night they could have put anything on there. Eventually the SBU agents called attesting witnesses, confiscated his computer and hard disk according to procedure, and late in the evening let Ruslan go. The next day he held a press conference where he told about his interrogation. His colleagues took to the streets to protest in support of the historian. The SBU didn’t know what to do with this. In response to the open criminal case against him, Ruslan filed a counterclaim—he lost every trial, but in two years the case against him was closed due to a “absence of a crime.”

While Ruslan was in Kyiv, the Prison on Lontsky Street museum was raided, all employees were interrogated, and documents the director had brought from Lithuania were confiscated. They were never returned. To be fair, Ruslan brought back new copies a year or two later. His computer and hard drive were returned four years later in 2014.

If other historians were interrogated, Zabily doesn’t know. He suspects not. But he knows for sure that many were scared. For example, SBU agents visited his friend, the writer Mykhailo Andrusiak and asked if Ruslan had given him any documents for his work on his books.

“They wanted to shut historians up so that they’d stop talking about the liberation movement, victims, the repressions. This was when Dmytro Tabachnyk was the minister of education and working on a history textbook together with Russia. They put pressure on Borys Gudziak, the president of Ukrainian Catholic University, Roman Krutsyk, the director of the Museum of Soviet Occupation, Hennadii Ivanushchenko, director of the Sumy Regional Archive was fired for publicizing documents about the Holodomor, they deprived the Institute of National Memory of its functions, closed museums.”

Ruslan’s interrogation was the last straw. Lawyers, historians, and dissidents began learning how archives work in other countries. They decided to change the law so that anyone could study the documents of repressive organs without risk to their own freedom.

They wanted to shut historians up so that they’d stop talking about the liberation movement, victims, the repressions. This was when Dmytro Tabachnyk was the minister of education and working on a history textbook together with Russia

The group created an electronic archive for the Center for the Study of the Liberation Movement in order to have access to important documents if they were reclassified—and in 2013–2014 that’s exactly what happened. They held discussions, surveys, round tables and in 2013 took the results to develop new legislation on access to the archives of repressive organs. Andrii Kohut worked in the group with Ruslan. He says that until 2013 they were working for themselves.

“The legislative project was written for the future and we didn’t know if it would ever be used. There was no chance of getting it ratified under Yanukovych. The secret of changing the course in the sphere of national memory lies in the fact that we were working even when no one believed in our cause. That’s why I always say, ‘When you want to achieve something, you don’t need to fear working for yourself. Everything can change literally in a day.”

Andrii says it was not difficult to convince the deputies of the necessity of passing the law. They had been working with ones who had to approve the resolution after the Revolution of Dignity since 2010. Oddly enough, archivists were against the law: the thinking was that no one would give them that, the authors of the law had no connection to archives, and anyway, they were too young. But in 2015 the members of parliament in fact approved a package of decommunization laws, among which was the law about access to archives.

“The worldview orientation of decommunization lost all meaning without access to the archives, for it is these documents that show the scale of the absurdity of life in the USSR. If you don’t know what life was like under the Soviets, the stories about those times seem unreal.”

In order to show the realia of the USSR, the SBU archive and partners are publishing books about the Polish and German “national operations”— in the USSR in the 1930s anyone who could have been a “a spy from a capitalist country” or a member of a “diversionary-insurgency group” was executed en masse. Within the framework of “national operations,” bullets were sent through almost 250,000 people: Germans, Greeks, Poles, Lithuanians, Estonians, Finns, Romanians, Chinese, Iranians—there are too many to list them all. The archive’s last book is called The Great Terror. The cover features a note about the start of the terror with Stalin’s signature; behind the cover you find hundreds of pages of documents authorizing the execution of more than 350,000 people in a year. “Enemy of the people” was the most frightening label of the time. The bloody troikas had to approve the verdict within 10 days, without the participation of the accused themselves, and the execution was carried out immediately. The system worked like a machine—1000 “enemies of the people” could be shot daily. All in all, in the two years of the Great Terror over 1.5 million people were killed or sent to the Gulag.

In order to simplify the work with archival documents, the SBU and its partners published a guide called The Right to Truth. It explains where to go and what to do when you are starting your search. There are similar guides for archives in countries in the Central Eastern European portion of the EU and countries of the Eastern Partnership.

Work Not for the SBU

“If someone had said in 2013 that I’d be working for the SBU, I would have that they were crazy.”

Andrii Kohut jokes that he was given his job in the SBU archive for New Year’s—he became the director on December 30, 2015, replacing Ihor Kulyk, who is now working to establish an archive at the Institute of National Memory to keep documents for institutions that cannot have archives. Among them is the SBU, whose primary function is to keep its own documents rather than those of the KGB.

“The SBU is not the legal successor to the KGB. In September 1991, the KGB was dismantled and an absolutely new organ was formed. The reatification commission admitted plenty of former KGB agents into the SBU, but de jure we are not the legal successor. We preserve documents that have nothing to do with today’s SBU. Western partners are always surprised that the SBU is in the business of history—for them it’s absurd.

But, unsurprisingly, there are advantages to the SBU’s archival work. Andrii says that the management understands—they must give people access to these documents. There was no resistance and the transition to the new system was painless.

“Earlier I would have said that I’d find it challenging in a bureaucratic system. But here everything is clearly regulated; there are rules for the work of archival institutions, rules for conducting business. The obligations of the director of an archive are administrative, but he must also know the methodology of historical work, the internal instructions, and the legislation, be able to understand historians. Work is possible thanks to this framework, since the work goes on regardless of who is in charge.”

The worldview orientation of decommunization lost all meaning without access to the archives, for it is these documents that show the scale of the absurdity of life in the USSR. If you don’t know what life was like under the Soviets, the stories about those times seem unreal

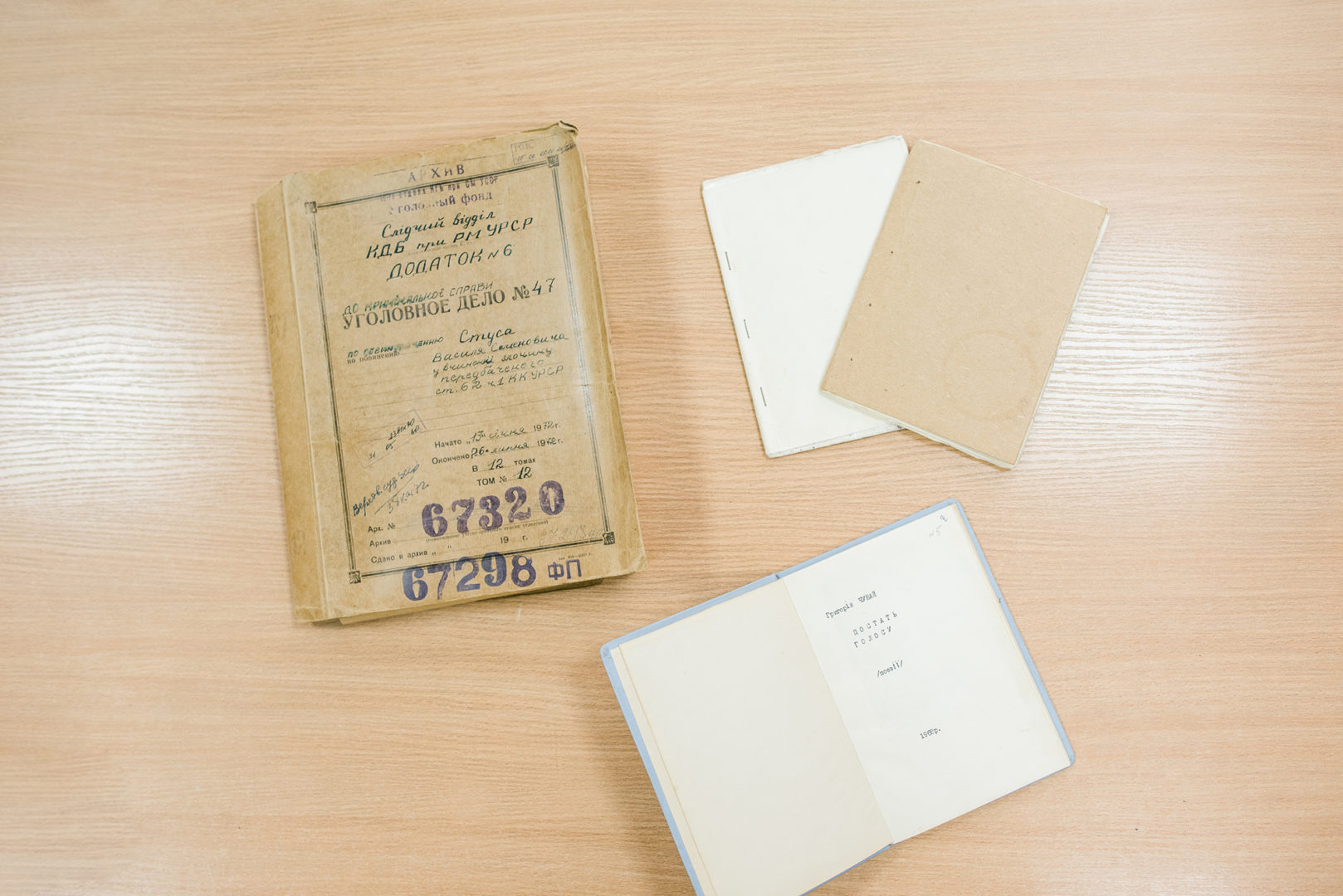

As soon as Andrii took his new position, he got invitations from journalists who wanted to talk to the young director of the SBU archive. That winter he was 36; he wore a red coat and a Keffiyeh around his neck. One time journalists from Channel 5 didn’t recognize him. Andrii is often asked what has most impressed him about his job in the archives, so he was ready for our question. He gets out the folder with Stus’s case and explains:

“Here we preserve documents about repressions. When you read the file of a specific person, it bothers you. But when there are hundreds of thousands, they turn into statistics. You become distanced from the emotional moments—it’s your job. But what truly impressed me was the poetry—the self-published volumes of Chubai, Kalynets, which they seized from Stus before his first imprisonment. Now songs from Chubai’s poems play on the radio, but then they were publications forbidden by the Soviet authorities.”

Translated by Ali Kinsella.

[This publication was created with support of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Norwegian government].

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More