Quiet Deliveries

“I need a bunting for a newborn. White without bows or ruching. Maybe with a little embroidery.” Before going into the children’s store, Yulia practiced these words a few times so she could avoid any extra questions from the sales clerk. “Do they have it or not? Is it the right size? Grab it and go.” A few times. In advance. In her mind.

Yulia pushed the shop door open. From all sides strollers, toys, onesies, booties, and mittens stared at her. She gathered herself and went up to the clerk.

“Do you have a white bunting for a boy? With nothing on it. Maybe with a little embroidery.”

“You know, we don’t have anything like that right now,” the clerk answered. But before Yulia had a chance to thank him and leave, he offered, “But we have bigger sizes. They’re three in one. They can be put into sleds. . .”

But Yulia wasn’t listening. Put the bunting in a sled? It’s June. The other shops also suggested something for the future—for two years, three, to grow into. But her son Liosha is just over a month old. He’s quite tiny and he needs the bunting now. White. Maybe with embroidery.

“We need it for a funeral,” Yulia couldn’t hold back and fired off. The clerk shut up and barely noticeably stepped back. Yulia ran out of the store.

Liosha was born at 28 weeks and lived a little more than a month. In pregnancy, the perinatal period begins at 22 weeks—this is when a fetus gets a chance of surviving outside its mother’s womb. According to the World Health Organization, every year around 15 million children are born preterm and 1 million of them die from complications. Per 2010 statistics, in Ukraine ten out of one thousand births during the perinatal period do not survive. The Ministry of Health’s Center for Medical Statistics shows that in 2017 alone, 17,000 miscarriages were recorded before 22 weeks.

Yet, regardless of the diagnosis or the term when a wanted child is lost, from the moment of the newborn’s death, mothers have a tough road ahead.

Liosha

“I knew it was going to be a boy, so when they confirmed it for me at the ultrasound, I wasn’t even surprised,” Yulia speaks quickly and emotionally, barely pausing. She has light hair and a soft look. The pictures of her kids on social media include a monochrome ultrasound that she has drawn angel wings on with a black marker. In the picture you can see the tiny nose and arms of Yulia’s son Liosha, who was born premature and lived just 39 days.

This was in 2012. Yulia and her husband Sasha had long been planning on having a child when they finally found out Yulia was pregnant.

“Everyone was happy,” Yulia smiles. “I have an older daughter, Lera, from a previous marriage, but this was my husband’s first child. I had been waiting for that moment so long that I was just unbelievably happy to be pregnant.”

Closer to week 18 the doctor told Yulia that her placenta was very low and there was a risk of bleeding. She was kept in the hospital for a week “for observation,” after which she was advised to rest more and take care of herself. Yulia had no stress and didn’t lift heavy objects. The doctors weren’t panicking and she didn’t worry either—she left the hospital and went about her ordinary life. The baby was the size of a pear.

One Friday, Yulia was heading home after work and noticed blood in the bathroom. A lot of blood.

“There was so much blood it was like someone had turned on a water faucet,” Yulia recalls. “I noted the time and called an ambulance. When the doctors arrived, I begged them to save the child.”

Then everything happened really fast. Yulia was transported to the perinatal center, paperwork was filled out, and they took her into the OR. They strapped her to the operating table, inserted a catheter, and prepared to stop the bleeding. The head doctor who brought in the ultrasound device said there was no placental abruption.

“Be thankful that we won’t be doing a C-section today,” the nurse told her.

That was week 24, and the fetus was the size of a cob of corn. Yulia couldn’t imagine that it was even possible to do a caesarean section so early in gestation. Maybe tying up the vessels, blocking the veins, anything—but not taking out the child.

“I said I didn’t want a C-section and started getting up,” Yulia says. “They laid me back down, gave me some shot, and took me to a room where they were prepping women for delivery. They told me not to get up. I laid there and prayed for the bleeding to stop. Everything was over by morning and they transferred me to the pathology ward.”

Yulia still didn’t know that there were only four weeks until her delivery. Over this time, despite bleeding she managed to avoid operations three more times. She found out that after week 30, the fetus is much stronger and has an easier time getting out. The last time, by now the fourth, she started bleeding in the middle of the night. The doctors again examined Yulia and told her that this time the placenta was starting to separate from the uterus and the child was suffocating. She had to give birth. Liosha was only 28 weeks old, weighed 2 lbs, 10 oz, and had already survived asphyxiation.

“The doctors said that we had a stable baby boy,” Yulia pauses before continuing. “They would only let us visit the ICU for an hour at a time during certain periods. But for me everything was in a fog. My husband said I shouldn’t rush off to see the baby, but I wanted to so badly, I cried and begged the doctors to let me in to see Liosha. This was about 11 o’clock at night and I couldn’t wait for visiting hours. Before I met him, I had never seen such a small child.”

Yulia and her husband believed everything was okay and tried not to think otherwise. The doctors said the child was a healthy weight and was gradually stabilizing. The parents named their son Oleksii, got a birth certificate, and invited a priest into the ICU to baptize the small boy. Yulia later learned that despite all the efforts of parents and doctors, the child could take a step back.

On Liosha’s 39th day of life, Yulia was at home changing clothes after returning from the hospital. Her older daughter Lera was also at home and her husband Sasha was supposed to come back from work soon.

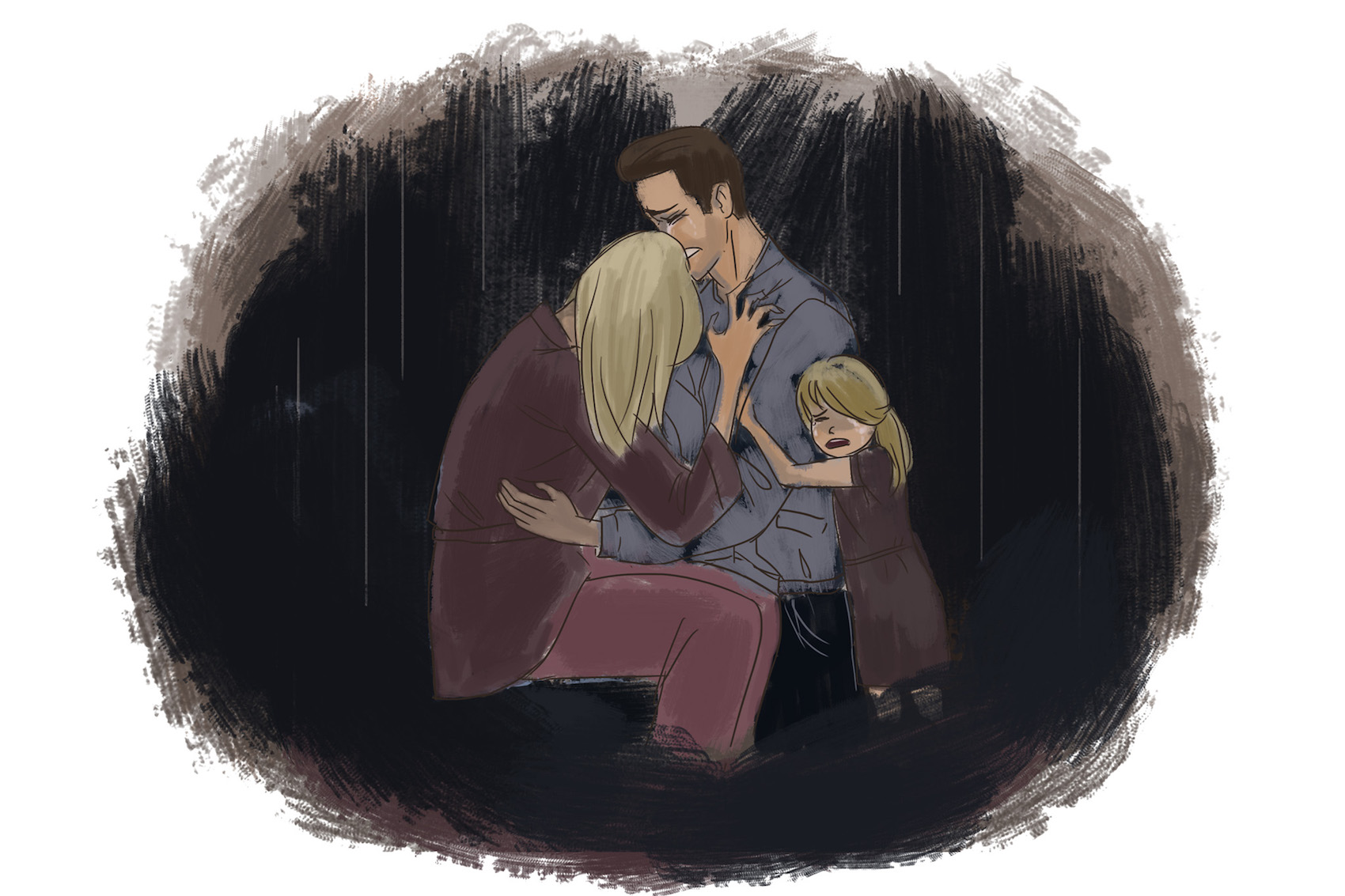

“I don’t know how much time passed from the moment that they called me from the hospital and said that Liosha was gone to when I came to. When I picked myself up, I could hear Lera crying in the next room. She came over and asked me, ‘Mom, is that it?’ I told her it was. We sat in the middle of the room hugging and crying until Sasha came home. When I told him everything, it was like the earth opened up underneath my feet and I fell into an abyss.”

The Abyss

A few chairs stand in the middle of the small room with warm-colored walls. The light from the sconce is dampened. Cardboard trees are arranged on a long low chest; children’s names hang from their branches. There are black-and-white photos on the walls in which different women, men, and children hold newborns wrapped in light swaddling cloths. Some of the babies fit into their parents’ palms; some are bigger. Some are in caps while others’ first hairs are coming in. In all the pictures, the newborns seem to sleep.

This is the farewell room at the OLVG West hospital in Amsterdam. Mothers, fathers, and older children come here along with others whose support the mother needs when it is time to say goodbye to the newborn. No one tries to take the child away; no one says it’s “better not to see it.” The mother can be with her child for as long as she needs to.

There aren’t any rooms like this in Ukraine. The doctor didn’t let Yulia come say goodbye to Liosha right away, explaining that the child had already been taken to the morgue. She said that he died because he was born prematurely, as a result of intraventricular hemorrhage and that there would be an autopsy. Later the parents were given a death certificate. Yulia and Sasha had to organize the funeral on their own, make arrangements for a spot in a Kyiv cemetery, and look for a white bunting for Liosha, maybe with embroidery, at shops full of toys, rattles, and various trinkets for newborns. It was unbearable.

Liosha was buried next to Yulia’s grandmother. Yulia said her goodbyes during the funeral.

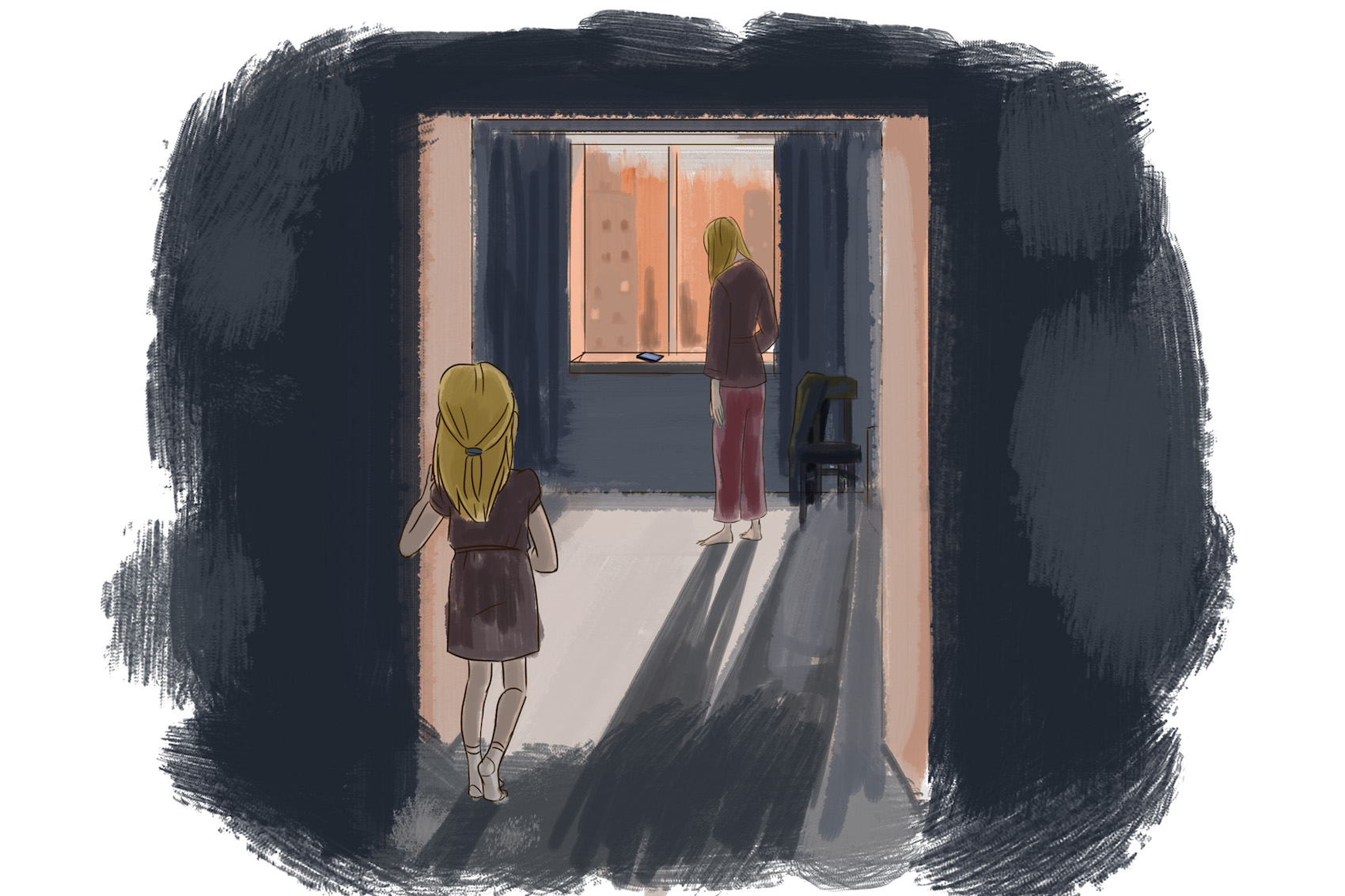

“I felt like everything was broken,” she recalls. “All my plans, everything I had thought about and felt when I was pregnant, when I gave birth, when I nursed—it was all ruined. I had to somehow keep the family together, and I was afraid of losing connection with my husband. But I didn’t want anything. I wanted to be left alone in my own little box and not to be bothered.”

Mothers, fathers, and older children come to the farewell room at the OLVG West hospital in Amsterdam along with others whose support the mother needs when it is time to say goodbye to the newborn. No one tries to take the child away; no one says it’s “better not to see it.” The mother can be with her child for as long as she needs to

Life churned around her. There were the clerks at the children’s stores who backed away silently when they heard that Yulia’s son had died. There were the doctors who came to say that she was still young, that she could have another. There were the relatives whom Yulia’s husband had to explain to, after their feeble congratulations on Liosha’s birth, that their son had died. There were the acquaintances who didn’t understand what she was so torn up about when she had an older daughter. There were simply people who shouted from up above the abyss to “hang in there,” but there was nothing to hang on to. Yulia slept, ate, and moved about, all within the abyss.

“I couldn’t explain to people that this was a child who had a place in our family,” Yulia says. “It wasn’t just something we had that went bad, so we got rid of it and forgot. We have no children in his stead. We have no children who could replace Liosha. He is one more our child of ours.”

Yulia tried going to a psychologist, but it didn’t help. Behind each one of his questions she could recognize the psychology textbook she herself had studied at the institute. She never looked for a different specialist. After a prolonged leave in connection with her difficult delivery, she returned to work and started gradually letting go of her stress on her own. And started paying more attention to her older daughter and husband.

Doctors advised Yulia to wait a year before getting pregnant again, but from cycle to cycle nothing happened. She went from one doctor to the next and ended up having to have an operation. Eventually she found out she was expecting again.

“This time I didn’t even breathe,” she laughs. “I rested a lot and listened to every one of the fetus’s movements in my womb. It wasn’t until after week 30 that I realized everything was going to be different this time. That’s when I decided I couldn’t carry the fear of death with me into this pregnancy. I had to let go of it and and only hold on to the sweet memory of Liosha.”

Yulia’s second son, Tymofii, was born without any complications. Yulia was unbelievably happy and while they remained in the maternity ward constantly listened to the baby boy, sat near him checking he wasn’t turning blue or suffocating. The doctors asked why Yulia was constantly poking at him. She tried explaining that her last pregnancy ended in the death of her child. In response, she was advised not to think about that since it was in the past. Here she had a healthy child, so why was she thinking about the dead one?

There is no medical protocol in Ukraine to regulate communication between women who have lost children and medical staff. The last directive advising on the “tactics of medical personnel in the case of a stillbirth or the death of a child in the department of obstetrics and gynecology” expired in 2014. According to information provided by the organization Natural Laws Ukraine (Pryrodni prava Ukraïna), doctors often neglect to support women emotionally—they simply don’t understand how badly women need this help.

“The first person a woman talks to after she learns she’s lost a child is the doctor,” says Alina Dunaievska, a midwife and gynecologist. “Unfortunately, the psychological training that med schools offer is quite weak. I had a class on medical psychology, but it was cursory and quick. It failed to provide necessary information on how to talk to someone who has experienced a loss. Of course, the patient can later go see a psychologist, and it’s good that a few delivery wards now have such experts on staff. But doctors should know what to say to someone in a state of shock. Many of them simply don’t.”

“‘Don’t cry, you’ll have another,’ ‘let’s try to calm down,’ this is the kind of support that makes you want to tell someone to simply shut up and go away,” Yulia says. “No one in the hospital treated my story seriously. Everyone just downplayed it and tried to talk me into banishing the bad thoughts from my head. They said that I’d forget everything once I got busy with new worries. But seven years have passed since Liosha’s death and no one has forgotten anything.”

Nadia and Olia

Eighteen years ago, Natalia found out she was pregnant for a second time. Her son was three and her first pregnancy had no complications. Up until week 20, everything was fine with her second pregnancy, too. That was when she started experiencing light bleeding.

“I could feel that the child was alive. It was kicking,” Natalia recalls. “When I went to the gyno, they told me that it sometimes happens and prescribed me some medicine. They recommended taking vitamins. I refused hospitalization.”

The next day Natalia’s contractions started. She didn’t immediately understand that she was giving birth, but the pain got stronger. She can’t remember what the EMTs asked her about or why they asked her at the hospital reception when her menarche occurred. She only remembers that everything happened extremely slowly and that she never made it to the OR—the child was born in the waiting room.

They didn’t let me say goodbye. I asked the nurse to show me the child, but she said it ‘wasn’t allowed.’ It was only when I asked that they told me I had had a girl

A woman has the right to carry a child to term even if tests show that the child will have birth defects that will cause it to die after birth. For these cases, various countries have perinatal hospices where the mother and other relatives can say goodbye to the child with dignity and receive necessary psychological support. There are no perinatal hospices in Ukraine.

Natalia knows that there are farewell rooms in the maternity wards of hospitals abroad, but eighteen years ago in Ukraine she wasn’t even allowed to look at her own child.

“They didn’t let me say goodbye,” Natalia says calmly. “I asked the nurse to show me the child, but she said it ‘wasn’t allowed.’ It was only when I asked that they told me I had had a girl.”

Natalia didn’t go see a psychologist then, because she didn’t know whom to go to. Her husband didn’t support her emotionally and thought he had it worse than she. Natalia was left alone with questions no one had answers to: Why did this happen? Why right in the middle of the pregnancy? Was it because she lifted something heavy? When she was pregnant for the third time, she was constantly afraid that she would have another miscarriage. She delivered suddenly in the middle of the night at home without any doctors at 20 weeks, just like before. She had no time to do anything, not even call an ambulance. Her daughter was the size of her palm. She did not survive.

“I held her in my hands and cried and cried and cried. I was so shocked that it never occurred to me to somehow say goodbye to her. My husband was hysterical when he saw us. He blamed everything on me. I refused to go to the hospital where my second child was born in the waiting room and agreed only to the gynecological department of the military hospital.”

It was August. Natalia spent five days in a hospital bed. No one bothered her. No one said she wasn’t the first one this had happened to. No one forced her to cook borshch or wash her husband’s socks. She cried a lot, went on walks in the hospital yard, read books, and listened to the silence.

We don’t have a culture of death at all. Families try not to touch on this topic or talk to children about it. When something happens to relatives, everyone tries to fence themselves off and somehow talk away this loss. But there are no families that haven’t faced death

“My roommates knew what had happened and left me alone,” Natalia recalls. “Only one of them came up to me, stroked my head when I was crying, and left. They didn’t prevent me from being in my emotions. Relatives and friends would call and write. My mom had also lost a child. She told me that it happens to many women, but that didn’t make me feel any better.”

“Unfortunately, we don’t have a culture of saying goodbye to a child in maternity hospitals,” Dr. Alina Dunaievska explains. “But this isn’t limited to perinatology. We don’t have a culture of death at all. Families try not to touch on this topic or talk to children about it. When something happens to relatives, everyone tries to fence themselves off and somehow talk away this loss. But there are no families that haven’t faced death. Perinatal deaths are just part of it.”

Natalia gradually said goodbye to the daughters she lost. She meditated, talked to them in her thoughts, wrote them letters, and performed symbolic farewell rites. Gradually she realized that not everything depended on her efforts or skills, that she couldn’t control everything. Thus Natalia began to let go her pain.

“What were your kids’ names?” I ask. In front of me sits a pretty woman with penetrating bright eyes telling me the story of her losses absolutely calmly and steadily.

“They didn’t have names yet. They left too soon,” Natalia just barely looks away. “I only named them for myself. The older one was Nadia, and the younger was Olia. Of course, I’ve lost the feeling of terrible grief long ago, but I still cry for them sometimes and I still remember them.”

Little One

According to Ukrainian law, losing a fetus to premature delivery up to the 22nd week is considered a spontaneous abortion, or simply, a miscarriage. Eighteen years ago, there were over 15,000 spontaneous abortions in Ukraine. In 2017, the Ministry of Health’s Center for Medical Statistics recorded over 11,000 such incidents, of which 72% occurred before week 12.

Anna’s third pregnancy also ended very early—during week five. She already had two children, a girl and a boy. She knew that miscarriages could occur at such an early stage, but she never thought it would be her case.

“I called it Little One. Before even a month had gone by, I was imagining pushing the stroller,” Anna smiles. “Even though it was so early, all my relatives and friends knew I was pregnant.”

Anna and her husband were returning home from visiting friends when she saw the blood, lots of blood. She called the doctor. Her doctor recommended staying at home and waiting—the fetus would either “reattach” and the pregnancy would continue, or it would release. So early in a pregnancy, very little can be done. The main thing is for the mother to pay attention to her physical feelings and stay in constant contact with the doctor.

“The doctor explained that this was a European practice. If I had gone to the hospital at that moment, they would have admitted me and given me a ‘cleaning.’”

“Cleaning,” or dilation and curettage, is one of the methods that is used in Ukraine in the case of a missed abortion. Now it is resorted to extremely rarely since this mechanical procedure is damaging for women’s health. Doctors also prefer waiting, or more often a medical abortion or a vacuum procedure. At the same time, because of a lack of medical personnel and a high level of professional burnout, midwives just don’t have enough time for everyone to wait it out. So Anna stayed at home and started waiting on her own.

At that moment, Anna was afraid of her own body. There was a lot of blood. She was sure the fetus wouldn’t make it. Anna started looking for reasons in her mind. Was it because she lifted that jar of pickles? Was it because her husband smokes? Was it because someone gave her an untoward look? Was it because she told everyone earlier than she should have?

“I was driving these thoughts away, but I needed explanations as to why there was no miracle, why the child we wanted so badly was gone.”

In the fifth week of gestation, the fetus is no bigger than a pomegranate seed. Anna’s seed is buried in her favorite place—on a lakeshore among the roots of a spreading birch.

Anna was struck by unspeakable horror. She cried and screamed for a few days. She put on her coat and hood and continued living in her tiny hut. Her husband initially supported her, but by the fourth day he gave up. Anna didn’t want to escape the grief; she wanted to live it.

Gradually she started coming out of this state. At first she and her younger son made a small fairy out of wool and called it Little One. Her children know that they had a sister but something happened and she is no more. There is life and there is death; they know it happens. But this doesn’t mean that their mother doesn’t miss Little One.

“I only surfaced on the fortieth day,” Anna remembers. “Until then I simply grieved. I wanted to literally sink to the bottom. But later a psychotherapist asked me, ‘Why the bottom?’ At that moment, it was like something clicked in me.”

In her online profile on social media, Anna calls herself the mother of three children and one angel

Anna got pregnant again four months later and her fear returned in a new wave. For days she would lie in bed, scared of moving without a physical reason to. She was afraid of getting used to the new fetus. After week five, she was finally able to breathe.

“That’s when I found out what depression is. I was sad after Little One—understandably so—but here there was no reason to grieve. It was like I was underwater,” Anna thinks and squints her dark brown eyes. “I guess experience is like stones. They tumble down the hill and only crack when it’s necessary.”

Memory

Now Anna herself works as a psychotherapist and attends births as a doula. She is raising her two older children and her youngest, two-year-old Sonia. For now she’s not part of any support groups since she is afraid of emotional overload.

After the loss of Little One, Anna started worrying about her children much more, thinking about their feelings, and paying them more attention. But at the same time, she is grateful for every day they are with her.

On the anniversary of the loss, Anna invariably goes to the place near the lake where Little One is buried. In her online profile on social media, Anna calls herself the mother of three children and one angel.

***

Natalia divorced her husband and later married someone else. She got pregnant two more times after two losses. Both times she was terrified that everything would repeat again. Both times she gave birth to healthy children—a girl from her first marriage, and a boy from her second.

Natalia found a passion in psychology, got a second degree, and defended her thesis. She writes texts on maternity and delivery and offers consultations for pregnant women and mothers, including on the subject of loss. She is disappointed with Ukrainian medicine, but she dreams that women in maternity hospitals will never feel the pain and fear like she did many years ago.

This year Nadia would have been 18 and Olia 16. There’s no year that Natalia forgets to calculate her daughters’ ages.

***

After Liosha’s death, Yulia grew much closer to her older daughter Lera. Later she gave birth to two sons, Tymofii (5) and Tykhon (2), who was also born prematurely at 35 weeks.

Now Yulia helps other women who have experienced loss or premature delivery. She joined Early Birds, the Association of Parents of Premature Children. She moderates a chat where mothers of these “eager beavers” can share their experiences. Yulia herself also contributes to social groups for moms who have lost a baby.

Liosha would have been seven this year. His birthday and the day he died are memorial days in Yulia’s family. Only recently she and her daughter Lera realized that last year he could have gone to school with his peers. Yulia openly says that she is the mother of four children.

There hasn’t been a day that she hasn’t thought about Liosha

Translated by Ali Kinsella.

[This publication was created with support of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Norwegian government].

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More