Lenin and the Void

Almost six years ago, the Ukrainian “Lenin Fall” (demolition of monuments to Vladimir Lenin) left empty spaces and pedestals, the new meaning for which is still being sought: the monument to the Bible in Rivne region, the monument to the sugar beets in Mykolaiv region, the Virgin Mary in Kryvyi Rih, and Cipollino in Luhansk region. Travelling art objects are erected on Lenin’s place in Kyiv—first the “monument” to the creator of Bitcoin, then a giant blue hand by a Romanian sculptor, and now there is a sculpture titled “Confrontation”. Some cities, such as Kharkiv, Yampil and Bakhmut, removed even the pedestals, paving or tiling the lots for good. Like there was nothing at all.

Yet, in Chernihiv, there is still a gaping hole in the tattered soil where Lenin once stood. The search for its meaningful filling is long and controversial.

***

1967. A pedestal is urgently needed for Lenin in Chernihiv. The local regional committee is worried. Architects are avoiding the job, passing the buck to 40-year-old Viktor Ustinov, who came from Russia three years ago to become the Architect-in-Chief of Chernihiv. He is not popular here, which is why Ustinov believes they want to make him do the dangerous job.

Any mistake might cost him his career. Lenin is marching freely. The pedestal should emphasize the grandeur and simplicity of the bronze leader, and it must not appear that Lenin is falling.

Ustinov has no other choice but to agree.

“Time was running out before the unveiling, while the regional committee had not even decided on the exact place for the pedestal. Victor tackled any job like it was his last. In those weeks, Lenin completely took away my husband,” the architect’s wife Inga says.

Illich revealed himself in November 1967. A piece of white cloth was solemnly pulled from it and hundreds of hands burst into applause.

He looked ahead—the five-meter-tall monument, standing on a six-meter-tall pedestal—hiding his hands in the pockets of his coat, inspired and slightly reminding of Taras Shevchenko. It was obvious the sculptor had mastered the art of sculpting Tarases.

***

Forty-seven years later, on the night of February 21, 2014, the crowd beneath the monument is humming like a beehive, swaying like a wave. And today, the wave will strike. Lenin is looking above the people. His walk is still firm, despite he has a noose around his neck and a dozen men are already pulling the ropes down.

The educator Vasyl Chepurny, who is called the main decommunizer of the region, comments to journalists against the background of noise and applause: “The things happening now should have happened a long time ago if the city had adequate authorities. And now, everything is as Comrade Lenin taught us—a revolutionary creativity of the masses.”

In addition to the rage caused by the shootings in the capital, almost everyone here today have their own reasons for making a “revolution”.

Oleh Viktorovych stands separately from both the proponents and the opponents of overthrowing the communist leader. He says he always knew this day would come. The year when Lenin was erected, he was kicked out of his job for meeting a dissident.

“I had to stand in front of them, not sit, while my senior colleagues sat against the background of the portrait of Illich and told me that I was a “public renegade” and about the things happening to “unworthy” people. Now I have come to see what actually happens to them.” Tonight, the man who is almost eighty, will get rid of his last grievances with that staff meeting, where he was sentenced for apostasy.

Public activist Denys Murza is among those pulling the ropes. One of his great-grandfathers, he says, was an NKVD officer, while the other had his own creamery, so he was dispossessed all the way behind the Urals. Maybe Denys is now taking revenge on the former for the latter. Or maybe, he is taking revenge on this meaningless piece of stone as the embodiment of the damned regime. While the regime, during this very hour, is managing evacuation of its treasures before its last flight from the Mezhyhirya Residence.

***

Yet, there are people here ready to defend Illich. For some, he symbolizes the love for their quiet past, while others hide behind his thrown open coat from the turbulent future. One even draws out a gas pistol, but gets quickly sidelined.

Not to miss the historic moment, Chernihiv historian Sashko Bondar came to Lenin with a dozen nationalist friends. The ropes were already on its neck, when Sashko thought: “What if Lenin drops and the soil is unstable?” So he rushed to stop the people about to go down to a nearby underground walkway.

“Go home, Bandera, why did you come to our Chernihiv and are breaking everything here?!” a couple was angry with Sashko. But he explained again using the same local Ripky-Horodnia dialect: the walkway may collapse along with Lenin.

After all, it did no harm to anyone. However, historian Sashko waisted the historical moment: “While I was talking to the couple, Lenin was overthrown.”

The leader fell on his right side. Boys jumped on him singing. Using a loud-speaker, a member of the Svoboda party called for a fundraiser to erect a monument to the fallen at Maidan on Lenin’s place. People clapped. In the east, rapacious war was looming.

On the same night, volunteers went to bring down other Lenins in the region. And on the site of the one in Chernihiv a pedestal remained, which was painted with poetry, a flag, a coat of arms, and the “Freedom or Death” motto in early spring. After midnight, when everyone went to bed, Chernihiv resident Maksym Nychyporenko saw two people tapping the pedestal. Perhaps, they were estimating the cost of granite cladding.

***

Sometime before the monument was unveiled in 1967, the regional party committee put a silhouette on the pedestal for people to get used to the presence of the leader. For four years now, there has been a screaming void in the place of a former communist sanctuary, for the people to get used to its absence.

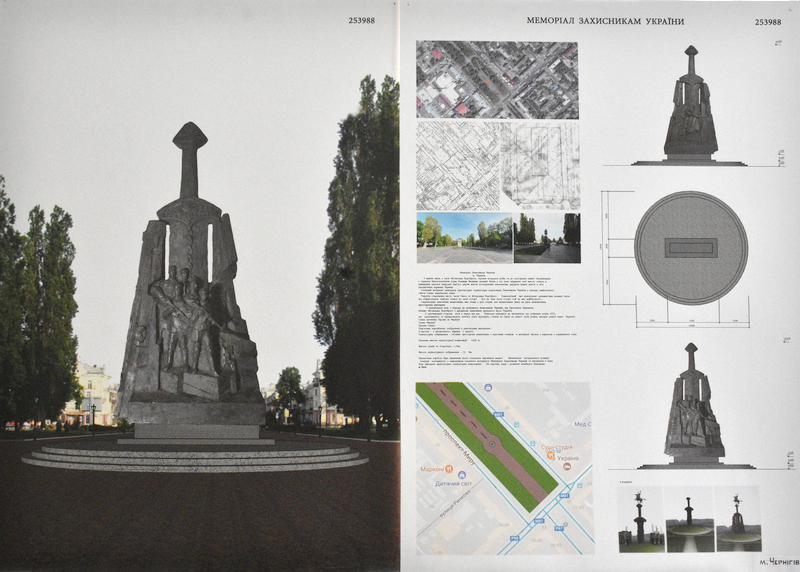

In 2017, the City Hall announces a competition for architectural solutions for the memorial to the defenders of Ukraine in the park where Illich used to be.

As befits, is should be “spiritually uplifting and high-principled”, accommodate many people at official ceremonies, prayers and leisure time activities, “bear educational, enlightening, ethical, patriotic, and spiritual meaning.” But it should not overload with a memorial function.

The project of a student architect from Kyiv wins. The girl proposes to equip the square with an artificial reservoir with imitation of currents, benches, memorial boards and steel sculptures, which would form a trident at a certain angle of view. The jury is pleased at first. But soon the girl is told that “the trident does not meet the task.”

It’s anybody’s guess whether they got tired of the trident, or the project did not please the Mayor, but they announce the second competition. New options are accepted until February 2018. No one has any idea yet how much the trident will be missed.

At the same time, the decision is made to disassemble the pedestal. Patriotic drawings have worn out, and it’s time to prepare the site for the memorial. Besides, the Mayor is upset that the pedestal blocks the view of the park and has “no semantic charge.”

***

On the morning of December 5, 2017, the city crews approach the pedestal to disassemble it in a day. By lunch, they have removed the granite cladding. In the midst of the wet fog, a grey and shabby six-meter-tall concrete base arises before them.

After a smoking break, they take to the hydraulic hammer, but the former Lenin’s stronghold breaks their tool. Over half a century under the granite, the concrete bristling with reinforcement has become too strong. Moreover, no one knows exactly how many meters of it is hidden in the ground.

Construction workers are going to go big—they ask for a diamond saw. It would cost the city half a million hryvnia. Some elderly woman is yelling under the pedestal for the concrete to be taken down by those who demolished Illich.

***

While they are trying to take the pedestal down in Chernihiv, its architect Viktor Ustinov is very hard of hearing. Only his wife can communicate with him. He hardly walks, but still paints. No place is left on any wall of the apartment in the building built for the party elites in the 1930s.

So, there is no point inquiring Ustinov. But one can still listen to him (in two weeks after our conversation Viktor Ustinov passed). He starts with his birth. Somewhere in the middle of the story the pedestal makes its entrance. Five meters of bronze had to be firmly grounded so that Lenin would not fall at the unveiling, or get knocked down by winds or earth shocks. Ideally, the monument had to stand forever.

“While working on the pedestal, I postponed all other work. I monitored the concrete and the cladding. My head was on it, like on the axeman’s block,” the architect recollects, stumbling.

He says, the principle goes back to ancient Greeks: in order to have a good composition, a pedestal should be somewhat tight for the monument.

“Such was my architectural task.”

“And now they can’t take your pedestal down!” his wife yells.

“Huh? Tell her not to interfere with the story,” Viktor smiles. “Nobody doubted the concrete. On the unveiling day, they were only afraid of the cladding, which was fixed in haste.”

Ustinov was not allowed to the grand opening by the police. He was so tired that he looked suspicious to them. The day before, an official from the regional committee advised him to pray. When they were unveiling the monument, Ustinov was doing vodka shots in his friend’s car.

When they started breaking the pedestal, family friends were worried if the elderly architect would survive it. The day before, the main city alley designed by him was completely dismantled. But he does not care too much. He is ninety-two, and says: “If they ask, I will erect another one.”

The architect’s wife unfolds a newspaper reading “Lenin or Stalin were a great despair for good artists. They longed to create something more poetic than the proletariat. So, they filled the void in themselves any way they could.”

The letter in her hands holds a secret recorded by one of her friends. The cunning artists made it so that Chernihiv Illich looked directly at St. Catherine’s Church, where he seemed to be “heading.” And although the church was closed, it was still a church.

***

“While it’s still cold, I will not scold you much, but the pedestal has to be removed. Yaroslav, this is no joke! Think how to tear the stela down,” Mayor Vladyslav Atroshenko addressed the head of the Housing and Communal Services.

The Mayor wants the cheapest option and invites Chernihiv residents to join. City resident Oleksandr Iznurenkov is prepared to take the stone out for six hundred thousand. He says he will use the balance to repair the orphanage, but this is even bolder than the diamond saw.

Another local Vadym Iovenko suggests a cheaper idea. He plans to demolish the pedestal using the rope saw method. The rope has diamonds in it too, but it only costs two hundred thousand. The plan is to wrap the stela, and the rope saw would move at high speed in a circle, gradually digging in and cutting the concrete.

They discussed the rock for two months—and took it down in a day.

***

The second contest of memorial ideas is a failure again.

The Most Holy Mother of God in a concrete arbor. On the facade—bronze Anti-Terrorist Operation warriors, led by Chernihiv Prince Mstyslav the Brave. The elevation above the mundanity of everyday life—eleven meters.

No good.

The gilded arch created by something looking like heads of wheat or two cow-tails is rejected without a second thought.

The hunched Jesus carrying his cross beneath the obelisk on which the Archangel Gabriel holds a trident-like lily—rejected after some thought.

A flower reminding of a mermaid’s tail sticking out of granite is not impressive.

An almost ten-meter-tall sword driven into the ground—impressive, but no.

There is no winner.

“The projects were expected to provide spatial solutions. Instead we got a dozen new statues. The defenders are all impersonalized,” laments the youngest architect on the jury in the City Hall meeting room filled with models.

Almost all the artists created a “Lenin substitute,” while they were supposed to create an architectural complex.

“Let’s leave a flat tile there,” decides the jury .

Chernihiv residents are indignant on social media.

Svitlana Dufina writes that the artists should put a beautiful female figure in Lenin’s place. Of a male one. Or both. To please the eye.

Oleksandr Moskalets asks to bring back the pedestal, and he is not alone.

The City Hall proposes to put a flowerbed there and forget about it.

***

“The cause of the great Lenin lives on. It is currently developing in many parts of the planet. No matter how much the monuments and symbols of the Soviet period of our history are trampled by nationalist thugs—the future of human civilization belongs to socialism and communism,” declared the now banned Communist Party in April 2018, and brought flowers to the empty lot on Lenin’s birthday. Sneakily and with no flags.

Some regional headquarters did not join the event—many still have nationalistically painted pedestals.

In Chernihiv, a woman with a basket and a man in an unzipped windbreaker leaned over the void.

“Lenin wasn’t buried there!” some passer-by yells.

“Go away, you brute!” another one bellows.

In the evening, Valentina Uvarivna—a communist without a party membership card—comes here. She brings flowers and crosses herself. Back in 1977, at a demonstration, she met her future husband on this place. On their wedding day, they brought Lenin a whole bouquet, bought with the last money they had.

“I cannot explain anything to you. Oh, dear God. I am a good person. I put flowers down here while there’s still a place to put them. A memorial to the fallen boys will be erected here soon and their mothers will be the ones to bring flowers. I will back off with my longing for the Soviet times. But until then, just let me have a good cry. This is my life, too. The city belongs to all of us.”

***

While walking in the public park one may trip over the empty space underneath Lenin. For six years, it has been filled with sand and concrete debree.

Therefore, Chernihiv resident Artem Puntus petitions to plant a fir tree there. A big live tree. The locals will be able to decorate it all together every year for the holidays. The petition gets the required number of signatures in a few weeks. The City Hall does not approve the idea—they have decided to create a memorial, so there will be a memorial. A fir tree is no memorial.

But in a year, the City Hall gets lost in its own confusion and says there are no plans for this territory.

So, it’s not about a memorial anymore.

Or a fir tree.

Or a flowerbed.

Naturally, it’s not about any Lenin either.

There is still a gaping hole in the tattered soil.

Photos by Valeriy Senchuk and Volodymyr Koval.

[This publication was created with support of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Norwegian government.]

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More