Charity Begins at Home

A simple and beautiful story of Vitaliy Dubil, a former resident of Dnipro city now living in Washington, can be undoubtedly included in the textbook on exemplary volunteering. Over the past seven years, he has sent seven 30-ton containers with US charitable medical equipment worth nearly $4 million to Ukrainian hospitals. Redundant or outdated for modern American health facilities, it is a definite benefit for modern Ukrainian ones, worn out and poor.

“Yet, our ‘Support Hospitals in Ukraine’ humanitarian project is, for the most part, assistance provided to Ukrainians by Ukrainians,” Vitaliy notes. “In 2016, when we sent our third humanitarian cargo, the news reported: American surgeons delivered equipment worth half a million dollars to Ukrainian doctors. For some reason, Ukrainians want to believe that some Mary Smith or Thomas Peterson from Boston or San Francisco decided to help them. Instead, 99.9% of US assistance is provided by Ukrainians or Americans of Ukrainian descent. By all those who care about the future of Ukraine.”

Personal Money and Free Time

Vitaly Dubil set out for the US state of Texas in 2008. He was born and raised in Dnipro, where he studied economics and was involved in the real estate industry. Vitaliy has long dreamed of being educated abroad, so when he won the Edmund S. Muskie Internship Program funded by the US government, he promptly went to study business at the University of Texas. The then crisis in the Ukrainian real estate market did not contribute to his ambitious plans. When he graduated, he realized that it was not a good time to go back home.

Later, Dubil was made an attractive offer to work in the Washington office of the International Finance Corporation—one of five organizations that are part of the World Bank Group.

“Setting off to study abroad, I did not plan to stay and work in North America. Although now I’m sure that I made the right choice. Otherwise, I would not have been able to help dozens of Ukrainian hospitals,” the volunteer explains.

He believes that his experience in project management was crucial for the successful development of the “Support Hospitals in Ukraine” volunteer initiative.

“It is a complex project that requires money, time, serious planning, coordination, and readiness to carry on till the end. Not everyone is able to launch and maintain something like this. During my volunteer work, I probably talked to five or six of my friends who wanted to launch similar projects in other countries, such as Kenya, Georgia, Peru, etc. And they always lacked some of the key factors,” Vitaliy says.

He calls his volunteering activity a job, because he actually spends more time on it than other volunteers usually do.

“For me, it is my second full-time job, but I do not earn money from it, quite the opposite—I spend money. My own money and almost all my free time,” the volunteer says, smiling. “But you know what? It’s not me who should complain.”

The Second Front

From a transplant surgeon, Maksym Kutovyi suddenly turned into an almost military doctor. “Almost military” since he did not go to the frontline and did not treat patients on the territory where military actions were taking place. However, from May 2014, all the wounded were taken directly from the battlefield to the nearest regional medical facilities. This is how the war in the east came right to the doors of the Dnipro Regional Clinical Hospital named after I. Mechnikov, where Maksym worked, bringing with it dirty jagged wounds, blood mixed with earth, and pleas for help from boys going crazy from pain and horror.

“Most cases we got were bad because the boys were not provided timely medical assistance. They remained wounded on the battlefield for several days. Consequently, they had much less chance of survival,” the doctor explains.

One day after his shift, Kutovyi got a call—they were summoning all the surgeons and traumatologists, for a bus from Ilovaisk was expected to arrive in half an hour, bringing lots of severe patients. More than one bus arrived that day. 150 wounded were brought just to their hospital alone.

“Of course, I saw people after terrible road accidents before, but they were single cases. And suddenly they were brought one after another—boys born between 1990-1995, with severe injuries, torn limbs and burns. It was terrifying,” he admits.

The hospital became the second front-line, held by doctors. Like the army in the east, at the beginning of the Anti-Terrorist Operation, doctors also went into battle without proper “weapons”. In their arsenal, they had some outdated equipment and a handful of medical consumables. But with the outbreak of hostilities, all the medicines and necessities for dressings and injury treatment, and even gloves were brought to the doctors by volunteers. They just needed to make a list.

“It’s a paradox, but that’s when we first felt like we were working in a US hospital,” Kutovyi recalls. “We used to count almost every pair of gloves, but now all the surgical tools, bandages and catheters were always at hand. For the first time in three decades, we had modern equipment in the hospital!”

On February 6, 2015, the first 40-foot container arrived in Dnipro, which became the hospital-city where the largest number of wounded were brought. The cargo worth half a million dollars was collected and sent by the “Support Hospitals in Ukraine” project volunteers specifically for the needs of the Basic Military Hospital and the Mechnikov Hospital. Half of the 26-ton cargo comprised modern equipment—ultrasound and X-ray machines, operating tables and lights, intensive care beds, wheelchairs, walkers, etc., and the other half was medical consumables for surgeries. The urgent need of this aid could hardly be overestimated—just two days later, the Mechnikov Hospital reported the arrival of their thousandth wounded.

The delivery was preceded by a complex nine-month process of finding partners, funds and connections. Nonetheless, in early March 2015, the charity initiative Facebook page announced their future delivery of two more containers for hospitals located in Dnipro and Zaporizhzhia.

Free and Priceless

During our conversation, Vitaliy Dubil emphasizes several times that he is a member of the expatriate community, not the Ukrainian diaspora. Expatriates are usually people who temporarily live and work in a foreign country and do not dismiss their returning home. Dubil believes that during the Euromaidan, it was Ukrainian expatriates of North America who were most noticeably involved in various social and charitable initiatives to support Ukraine.

After students were brutally beaten on the Maidan Nezaleznhosti on the last night of November 2013, more and more Ukrainians flocked to the White House and the G7 embassies in Washington. Here Vitaliy met Pavlo Fedorenko, a Ukrainian expatriate from Zaporizhzhia, who had lived in the United States for 15 years. The men became friends, and a bit later, after the war broke out in eastern Ukraine, they decided to somehow help their native county.

Talking to his relatives and friends living in Dnipro, Vitaliy often heard about a large number of wounded who were taken to the front-line city. Alarming news were reported more often by the media about Dnipro hospitals failing to cope with the workload. The healthcare sector that had already suffered chronic underfunding before the war, desperately needed help.

“We realized that Ukraine had never had experience in military surgery. The quality of the healthcare system had to be immediately boosted,” Dubil explains.

“During Pavlo’s student internship, he heard that there were charitable organizations operating in the United States that delivered medical equipment around the world. We seized on this idea.”

Shortly after, through some connections, the friends found Jeannie Martin—an American volunteer who had experience in running similar projects and was involved in organizing the delivery of humanitarian aid to Kenya and eastern Ukraine in the pre-war period. Jeannie recommended the men to cooperate with Project C.U.R.E., one of the world’s largest non-profit organizations collecting surplus or outdated medical equipment from American manufacturers and medical facilities, and sending it to developing countries. Ever since, Project C.U.R.E has been providing the project with medical equipment for Ukraine.

“According to American standards, medical equipment must be written off after a certain period, even if it still can serve for a long time,” Vitaliy Dubil explains. “All equipment is checked to be in good condition. Moreover, we also send special transformers that adapt the American voltage to the Ukrainian standard. Thereby, hospitals receive equipment that can be turned on straight away.”

The equipment must be not only in good condition, but also needed by hospitals. That’s why medical facilities provide their own lists of urgent needs beforehand, which Vitaliy agrees upon with the supplier. Project C.U.R.E checks the availability and suggests a composition for the cargo. Loading and shipping this free, although priceless equipment to Ukraine seem to be the easiest things to do.

Yet, as it turned out, it was the hardest! If you ever want to send a 30-ton, 40-foot container to someone overseas, keep in mind that it costs at least $22,000.

1:25

“Guys, I’m selling my two tickets to the Okean Elzy concert in New York, on October 17. All the money will be donated to a charity project to deliver 40-foot containers of medical equipment to hospitals in Dnipro, Kyiv and other cities,” Vitaliy Dubil wrote on his Facebook page six years ago, setting up an auction. The highest bid for the $150 lot—$500—was the first money raised by the volunteers.

They still had to raise another $21,500. Last year, the Ukrainian National Women’s League of America fully funded the delivery of a container for Okhmatdyt Hospital in Lviv and Zhytomyr Regional Children’s Clinical Hospital, while the Friends of Ukraine Defense Forces Fund in Toronto and volunteers from the United Help Ukraine non-profit charitable organization helped funding the delivery for Irpin Military Hospital and Zhytomyr Kuzminykh Brothers Rehabilitation Centre. In contrast, at the beginning of the humanitarian initiative, it was a challenge for the volunteers with no successful experience of running such projects.

The initiative to raise money for the first delivery was supported by colleagues, friends, friends of friends, and countless acquaintances. “Many a little makes a mickle”—volunteers were holding sales, selling souvenirs at the Embassy of Ukraine in the United States. One of the project’s biggest patrons was a cardiologist from Cleveland, Ohio, Yuri Deychakiwsky—born to Ukrainian immigrants—who donated about half a million dollars to various projects aiding Ukraine over the past two decades. Yet, mostly the volunteers donated their own money. For instance, Pavlo and his wife donated $5,000 to the project from the sale of their car.

“When we were raising funds to deliver our next containers, we were already treated as serious and reliable philanthropists. I have repeatedly received awards for charity and spoke at conferences, telling about the success of our initiative,” Vitaliy says.

Grant sponsors and partners were interested in the “Support Hospitals in Ukraine” project primarily because of the phenomenally successful project model—each dollar of donations pays for the delivery of medical equipment worth $25. Thereby, thanks to relatively small donations, the project manages to provide Ukrainian hospitals with equipment worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

By the end of 2015, the hospitals located in Dnipro and Zaporizhzhia had received two new containers of medical equipment from the “Support Hospitals in Ukraine” project volunteers, worth over $1 million. Since then, the project team has sent four more containers of equipment worth over $2 million to Ukraine. These days, Pavlo Fedorenko does not take an active part in the project, Jeannie Martin inspects recipient medical facilities and agrees on the lists of necessary equipment, while Vitaliy is involved in the management of operations, strategic development, and relations with partners and sponsors. In 2018, Serhii Sementsov and Mariia Toponenko joined the team to monitor the social impact of the project. Vitaliy does not complain, since due to all the experience, by now most processes have been systematized.

“It’s not for me to complain,” Vitaliy says again, answering the question about burnout and fatigue. “When we hear the stories about the boys who leave their small children, quit their jobs, and go to the front to defend their homeland, sit in the trenches in the cold and hot weather, and come back injured, we understand that it’s not for us to complain about fatigue or lack of money. These boys are my biggest motivation. As long as we can, we will carry on!”

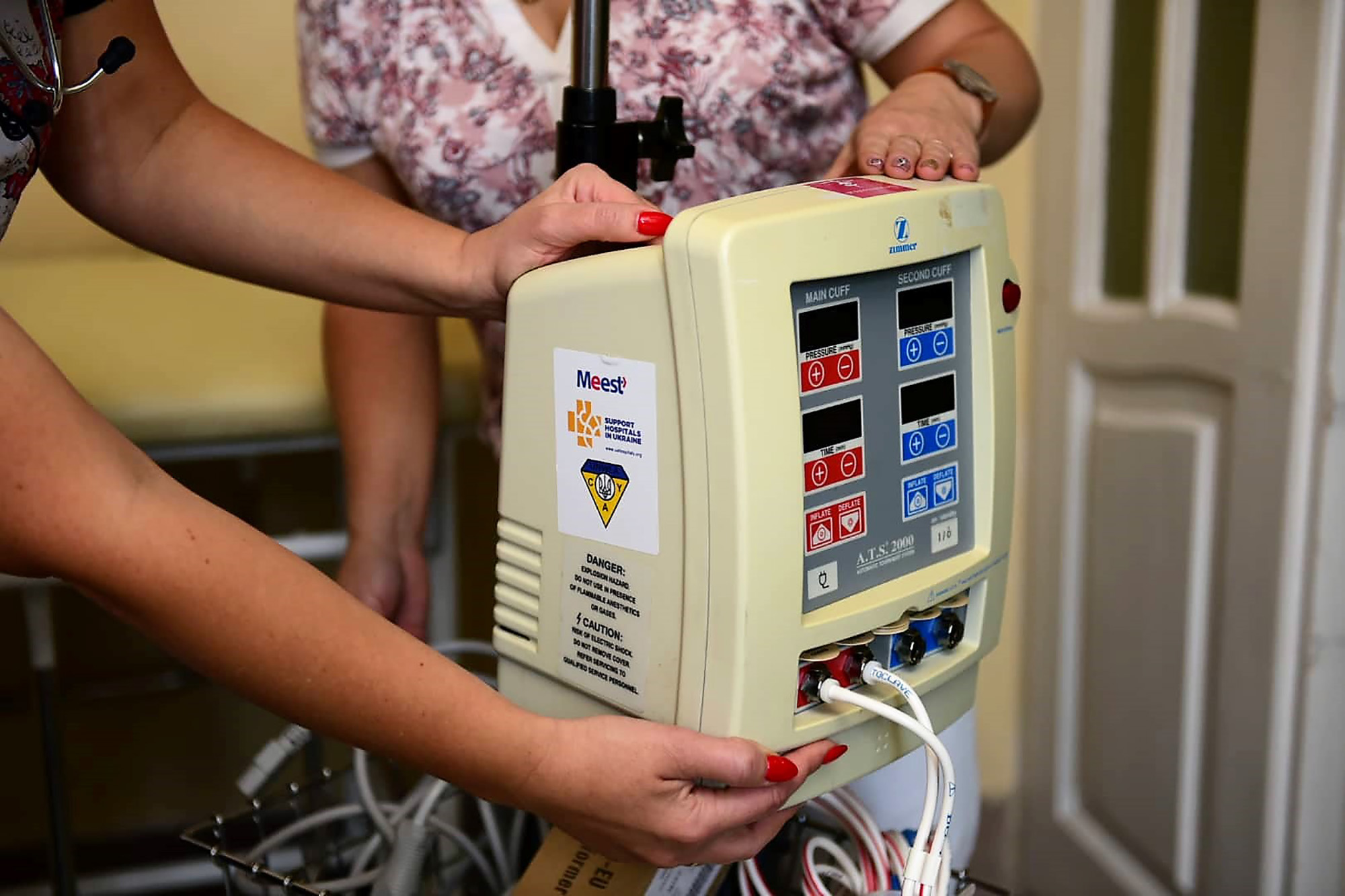

Razom

Modern medical equipment delivered to 20 hospitals in Kyiv, Dnipro, Zaporizhzhia, Zhytomyr, Irpin, Odesa, and Lviv has special stickers—“Support Hospitals in Ukraine,” marking the dedicated work of people on both sides of the Atlantic and thousands of saved lives. The founder of the project, Vitaliy Dubil, jokes that old equipment in Ukrainian hospitals has seen dinosaurs, so whenever he visits the Mechnikov Hospital in his native Dnipro, he is sincerely happy.

“I saw the equipment we sent in the operating room. The surgery is underway, and we look through the glass at our lights, our laparoscopy machine—which allows for non-invasive surgeries—our electrophoresis, and diagnostic equipment. Everything works and helps Ukrainian doctors.”

Two years ago, the Mechnikov Hospital reported that since the beginning of the war, they had successfully recovered 3,000 seriously wounded soldiers, and approximately 5,000 sick and injured patients from the war zone. Today, when the number of wounded decreased and hospitals got back to a more or less normal pre-war operation, Dubil and his colleagues decided not to wind down the project. Instead, they started looking for new partners to fund those medical areas that currently see an active development in Ukraine, namely neurosurgery, oncology and military rehabilitation.

Cooperating with other Ukrainian organizations, they manage to partially supply children’s hospitals, as well as support medical facilities in Ukraine during the COVID-19 pandemic in partnership with the “Razom for Ukraine”—a non-profit organization from New York. Vitaliy believes that the project is successful because of the trust people have in it—over the seven years of the project’s existence, it has always remained non-profit, there’s been full transparency and no administrative costs, because none of the volunteers get a cent for their work.

“I set two goals in the project,” Dubil explains. “One is obviously to deliver the medical equipment. And the other one is to share the success story of a humanitarian initiative implemented by Ukrainians living abroad. I would like to see the number of such initiatives grow, and for the people living in Ukraine to get rid of the stereotype that Ukrainians forget their homeland when they leave. They are doing a big job—that’s for sure.”

Photos were provided by the “Support Hospitals in Ukraine” project volunteers.

[This publication was created with support of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Norwegian government.]

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More