Between a Miracle and the Norm

Once during the height of fighting in eastern Ukraine, the Kharkiv architect Oleh Drozdov, a Kyivite well known as the man responsible for the reconstruction of the Theater in Podil, approached a Kharkiv millionaire, the owner of the Ahrotreid corporation Vsevolod Kozhemiako, and said that he wanted to start an architecture school.

Kozhemiako is a businessman who earned his capital in the nineties frequently named among the richest Ukrainians according to Forbes. In 2014 he started the Peace and Order (Myr i poriadok) foundation and began wiring money for clothes and equipment to soldiers in the Donbas. At that time, he had known Drozdov for nearly twenty years. They became friends when Drozdov built a few buildings for him and his partners. The architect told the millionaire the amount he would need to start his school: one and a half a million dollars.

Kozhemiako reacted emotionally, “Are you out of your mind?!” Drozdov listened to the whole set of clichés that everyone was spewing back then: we’re at war, ATO is just around the corner, and here you want to start a school . . .

“I waited for him to reconsider; I avoided answering for a while,” Kozhemiako recalls. “But he didn’t reconsider.” In 2016, the millionaire got his partner friends together and informed them that they needed to invest in the establishment of a new educational project. They told him that if he was on board, they were on board. In September 2017, the Kharkiv School of Architecture announced its opening.

The Norm

In order to understand the scale and importance of this event—the establishment of the KhSA—the whole context that Kharkiv, its residents, and architects have lived in for the last one hundred years must be explained.

From the time that the government in Ukraine was seized by Bolsheviks and Kharkiv became the Soviet capital, Constructivist architectural projects inspired by European Functionalism, the German Bauhaus school, and the works of architect Le Corbusier started appearing there. The main philosophy consists of the correspondence of form and materials to the structures’ function, the rational use of space, and urban planning. Architects from Russia and Europe poured into Kharkiv to build the new capital.

Architectural scholar, author of architectural guides to Kharkiv and Slavutych, and co-organizer of the Modernists conference Yevhenia Hubkina stood at the origins of the Kharkiv School of Architecture’s mission and program. She believes that Kharkiv was always a “city of outsiders.” Architects who hadn’t managed to establish themselves in developed countries or break out and achieve a certain status came here. Here they could become anyone they wanted.

For example, she says, the German Lotte Stam-Beese worked in Kharkiv: she was one of the first to enroll in the architecture department at the Bauhaus, but for a series of reasons she couldn’t finish her studies and find a job. She was welcomed with open arms in Kharkiv: among other things, in the early 1930s she took part in designing the neighborhood of the Kharkiv tractor factory (or KhTZ, as the people call it).

Today it is considered a landmark for the city: on the one hand, the unique architectural ensemble has been preserved; on the other, it is one of the most crime-ridden neighborhoods. It has also been suggested that the construction of the factory and the related costs marked the start of the Holodomor. Even today some people call Kharkiv the “capital of the Holodomor.”

In 1934 Kharkiv handed over its capital status to Kyiv. Stalin saw to it that Constructivism was repressed. The Union of Architects took over control of the country’s appearance and architects began building Socialist Realism, which symbolized the start of the epoch of authoritarianism. Eventually, the city was embroiled in World War Two and the German occupation, and later came a prolonged period of stagnation.

Architect Oleh Drozdov was born during this stagnation.

A Miracle

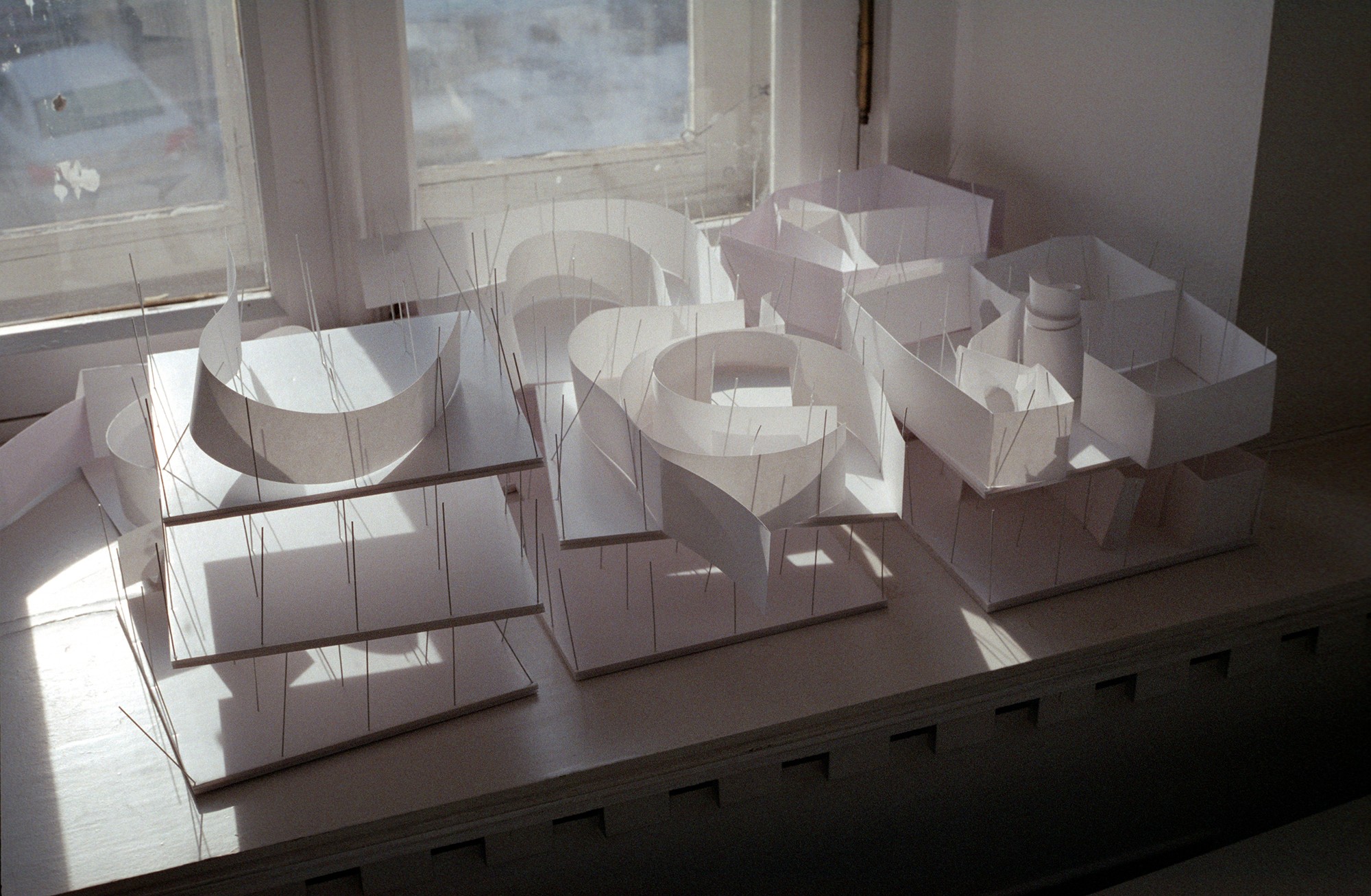

“I’m of the generation in which no one was thinking about anything very seriously,” Oleh says. We are talking in the lecture hall of the KhSA where students usually discuss their projects. White sheets of cardstock with words written by hand in black hang on the walls: “How to live together?” This question, formulated in the 1970s by the French philosopher Roland Barthes in a series of lectures at the Collège de France, has been bothering humanity since the times of Socrates, if not earlier.

“No future, no future for you,” Drozdov quotes a Sex Pistols song to explain the mood that his generation came of age in. Oleh is wearing all black. Against the background of the white walls, white columns, and white sheets with the questions, he seems to be part of someone’s installation.

“It never occurred to us that we could design and build something,” he says. “Only one out of two hundred could get somewhere in the system and come close to the chance of doing architecture in the 1980s. We did paper architecture. We had underground exhibitions. We drank. We had zero expectations for our futures. There was no optimism.”

The window into the future appeared with the collapse of the Soviet Union—and it was immediately closed. Architects began being used to create the world-famous post-Soviet vendor kiosks that remain exotic today to Western observers

The window into the future appeared with the collapse of the Soviet Union—and it was immediately closed. Architects began being used to create the world-famous post-Soviet vendor kiosks that remain exotic today to Western observers.

In Drozdov’s words, the “time of depression, kiosks, and mass emigration” had begun. He and many of his colleagues left for developed countries. They returned only in the early 2000s when public rejection of the appearance of Ukrainian cities had reached its limits and clients’ tastes had been readied by the infiltration of the Western urban mainstream. Just like in the 1920s, the outsiders began returning to Kharkiv.

The Norm

The smallish Kontorska Street, which runs parallel to the broad Poltavskyi Shliakh, one of the city’s main arteries connecting downtown to the Southern Train Station, leads to the building that the Kharkiv School of Architecture today occupies. The majority of the buildings here were built in the late 19th century out of dark red brick. The first-floor windows are behind grates and they are all covered in thick spiderwebs. The entryways are filled with the junk dragged here by residents over many decades. Some people hide themselves from their neighbors behind partitions cobbled from old doors. Many buildings are abandoned or on their last legs. In a word, it’s depressing.

The former casino building, which wouldn’t be out of place in old New York or some noir film, dominates the neighborhood. The casino has survived a few fires and now stands bare, its windows boarded-up rather than filled with glass panes. The building’s roof features a quote from an installation of one of the founders of Moscow Conceptualism who was born in Dnipro, Ilya Kabakov: “Not everyone will be taken into the future.”

The founders of KhSA bought the building at 5 Kontorska at auction in 2016. In the late 19th century, the two-story building was built by a local merchant for holding official receptions and a home theater, but after the revolution of 1905 he went bankrupt and gave it to the municipality. Later it was a city ballet school, then the main post office, and after WWII, home to secretarial courses.

In the nineties, the merchant building ended up among Inna Bohoslovska’s properties. At that time she was the owner of legal firms that catered to local big capital. In the 2000s Bohoslovska became a politician and migrated between various political projects (in turn, for example, supporting both Viktor Yushchenko and Viktor Yanukovych). Together with her common-law husband Yurii Ryntovt, she founded a private concert and educational club, RodDom, in the home where they held conferences and European and Russian stars performed. Ryntovt is considered a legend of Kharkiv interior design. In the words of architect Drozdov, it was his friend Ryntovt who first thought it wouldn’t be a bad idea to start something like an architecture school in “Bohoslovska’s building.”

When the building on Kontorska St. was taken from Bohoslovska for being millions of hryvnias in debt and put up for auction, Drozdov immediately told Kozhemiako that they definitely had to buy it. The millionaire threw up his hands: well, if we must . . . The founders of the KhSA bought “Bohoslovska’s building” for a relatively small sum—according to Kozhemiako, 600–700 thousand dollars. It hardly needed any repair.

A Miracle

An accident at the Kharkiv National University of Construction and Architecture (KhNUBA) played a key role in creating the KhSA.

Oleh Drozdov was invited to chair the exam committee for graduation projects at the university. A working architect who had completed a series of notable projects, it was his first time taking part in something like that.

“I saw the level there. A student proposed putting a car dealership alongside a city beach in recreation territory,” Drozdov says somewhat harshly. “Or, instead of a park, a shopping mall. And these diplomas for students were clearly slapped together by one of those professionals who normally makes typical prefab, modular buildings.”

Apparently, this has long been happening in all architecture colleges, but it truly enraged Drozdov when he saw with his own eyes what was happening to the profession from the get-go. Why was this happening? His answer: degradation.

“The absence of motivation, the absence of a picture of the future world, the absence of methods, the absence of goals,” he says. “At that moment I realized that our school was simply necessary, because professional life is impossible without a professional community. And a school is probably the only way to form this community.”

Not long after the incident at KhNUBA, Oleh called Kozhemiako and told him his plan. In response he received a tirade about the secondariness of everything not related to the front. The architect was not surprised by this reaction: over his years of work in Ukraine, he had gotten used to the fact that the fundamental questions of being—among which architecture comes in at practically last place—take a backseat. The post-Soviet person is always in a hurry to get somewhere and doesn’t notice anything around her. For our residents, the street is what has to be crossed quickly at a red light without looking under their feet, without paying attention to details of facades, not noticing what the walls of their own houses are made of.

The Norm

In 2015, the Kharkiv architect received his first commission for a large project in Kyiv—the reconstruction of the Theater in Podil. It was his first Kyiv project and he executed it flawlessly despite the “protesting grandmas” and “couch critics,” who had never before taken an interest in architecture. The building would not have raised any eyebrows in, for example, Berlin or even Kharkiv where references to Constructivism in architecture are not simply normal, but natural. But for the baroque Andriivskyi Descent it was an absolute provocation.

It was even called the “crematorium in Podil,” clearly with no awareness of the irony of such a comparison: the Kyiv crematorium is a masterpiece of Brutalist architecture on a global level, and its creator, Avraam Miletsky, was the architect of many famous Modernist buildings in Soviet Kyiv.

“What is architecture?” Oleh Drozdov ponders. “Here’s how I see the process: you have certain ideas and dreams and you’re looking for a convenient partner to realize them. So when a client approaches you and says, ‘You know, I need this,’ and you had just been dreaming about it yesterday. Or just right then, in that moment, something starts churning within you; like you had just been dreaming and you get a place to realize your dream. Sometimes it is very important to immerse your clients in this idea, this dream so they share it from the very beginning, even before you shake hands or sign a contract. It is very important that they join the team that corresponds to your goals.”

The relationship between the architect and the client is the critically important basis of the profession in post-Soviet space. How these relationships are built and the client is demonstrates the very essence of social relations in general. For example, over 70 years the client for architecture in Ukraine was the Soviet state. Rather, at first the Soviet state commissioned architecture to ensure the functioning of space and people with in it, but once Stalin’s authoritarian regime rose to power, it was to ensure control over and pressure on the people.

With the arrival of capitalism, big capital became the client and the key value was square footage. Architects began being used to design monsters that stole all available space from people. This theft was legitimized with the explanation that it was “the architect’s vision.”

Drozdov says that today’s architects mostly “practice prostitution” and take part in a criminal conspiracy, “whose only goal is not a future happy life, not someone’s happiness, not the environment, a smart, compact building or a safe, healthy city for the future, but simply the buying and selling of square feet.”

“Ninety percent of the architectural population serves precisely this goal,” he continues. “This is a deformed consciousness and a state from which it is very difficult to return. People go into it, probably, due to a lack of confidence or understanding of values, due to the absence of an aesthetic frame. All of this is laid during elementary school and during architecture school. And finally, we have virtually no institutions that could develop a genuine professional dialog or a critical reaction to what is happening.”

A Miracle

In February of this year, the contemporary culture journal 5.6 put out an issue dedicated to architecture, “Architecture. Community. Time.” It focused on the exotic—to a Western eye—aesthetic of Ukrainian Khrushchevkas. The absurdly extended balconies, panelled high-rises, gloomy bedroom communities, and kiosk tents that fill all available space—all of this is today seen as an indelible part of the architectural and cultural landscape of Ukraine. And as something that must be destroyed.

The Kharkiv School of Architecture appeared on what was already fertile critical ground. In 2007 the first CANactions festival of architecture and urbanism took place, which first raised the issue of whether they could stand architectural hell in Ukraine any longer. The words of festival founder and architect Viktor Zotov became one of the its slogans: “cities are people, not walls” and “we are the authority.” In 2015 an educational research platform that studies Ukrainian cities and their spatial potential was launched on the basis of this festival.

Urbanism research programs and centers (for example, the Center for Urban History in Lviv and City Code [Kod mista]), groups of urbanists (Urban Curators), design studios that specialize in urban construction and reimagining public space (Formografia Design), and communities that research Modernist architecture (Save Uzhhorod Modernism) have started popping up. Books on architecture and public space are also being published.

Today’s generation is trying to start a public dialog on the topic of the Soviet legacy and develop new architectural concepts and solutions for Ukrainian cities. To be fair, Yevhenia Hubkina believes this is happening because the environment is squeezing architects out of their profession and leading them into interdisciplinary spheres. She herself left architecture for research and educational projects, as did, for example, the guest editor of 5.6’s architecture issue, Oleksii Bykov.

“Ukraine is one of the most dormant of the countries that do not exist on the world architectural map,” Drozdov says. “There are a few exceptions, but they’ve shown up in the last five years. Both at war and after war, you have to decide constantly if you’re going to continue living or not. The second question is: How fully are you trying to live your life? Architecture is one of the important professions that serves society, its ambitions, its stability. And an institution [like KhSA] can start to slowly influence our educational institutions.”

Drozdov believes that the second Maidan and the war have activated a professional dialog about architecture and urban planning among Ukrainians. But it still suffers from a lack of systematization and support of the majority.

Architecture is a servile profession. You execute the orders of either the government or large companies. But architecture is really expression. I want there to be a generation of the young and angry who are capable of telling the client, ‘no, your vision is tasteless’

A Possible Miracle

During the Open House Days at KhSA, one of the auditoriums was named The Miracle. They held workshops for incoming students there and on ordinary school days it hosts critiques of student projects. Near the entrance to the auditorium, employees hung an eponymous banner right above the manual fire alarm with the words “The Norm” on a shield. Drozdov laughs when I point out this spontaneous dialectic.

The fabric of post-Soviet architecture is constantly being pulled to two extremes. The norm is the formal standards that selectively hinder the creation of something new and the violation of the norms as part of corruption for the sake of stealing space. The miracle is the rare chance to create something according to honest, transparent rules of the game. Sometimes in our reality, the miracle is just upholding the norms. Nobody yet knows how to make it such that the norm remains the norm and the miracle reserves the right to anything.

“Our goal is to create a new Ukrainian tradition,” Drozdov explains. “We are rethinking everything that came before us as tradition and building something new on its foundation. It is impossible to build something in an empty space. But we cannot simply accept a ‘package’ from the previous generation. We need to do everything over.”

In spirit, KhSA is partly a Ukrainian Strelka. The Strelka Institute of Media, Architecture, and Design was established in 2009 in Moscow by billionaire Aleksandr Mamut, publisher Ilya Oskolkov-Tsentsiper, and world-famous Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas. Since opening, the Institute’s students and instructors have produced tons of interesting and successful projects to develop the urban environment, such as the reconstruction of Gorky Park. Incidentally, the Kharkiv mayor’s office tried to “copy” the concept for its own Gorky Park.

One of the people responsible for the bachelor’s degree program at KhSA is Polish architect and researcher Kuba Snopek. He was among the first students at Strelka and worked there for four years until 2015. In 2018 he was offered a position on the Kharkiv team. Snopek says that the opening of the school of architecture in Kharkiv was a major event among architects and scholars. “The world doesn’t see new architecture schools all that often,” he says.

Snopek agrees with Drozdov in confirming that Ukraine needs a new architecture and professional reforms.

“This is a global challenge. All over the world architecture is undergoing a crisis. In the first half of the 20th century, the architect was a person with a great reputation and power. In the 1970s–80s in the West, idealism started disappearing and architecture became commercial. There’s a lack of a new program. KhSA appeared at the intersection of different challenges: what should architecture look like under the conditions of the Ukrainian climate, in places with a complicated history, with a certain cultural practice of using space? Besides this, there are the questions: Who is an architect in the 2020s? What does the profession look like? Should decisions be imposed on [clients] and to what degree must architects listen to what clients and society want?”

“Architecture is a servile profession. You execute the orders of either the government or large companies,” says Hubkina. “But architecture is really expression. And today in Ukraine there is no one to express anything, since there are conformists everywhere. This is normal; it’s just the era. However, I want there to be a generation of the young and angry who are capable of telling the client, ‘no, your vision is tasteless,’ and instead create their own, courageous expression that coincides with their own values.”

Many independent architects see in KhSA an alternative that can take over the role of being a counterweight to conformism and resist the “conspiracy” between architects and clients.

Drozdov believes that for there to be a revolt of architects against the system, “we need the number of people who can think critically and set the agenda of the day to grow from zero point something percent to 5–7 percent.”

“There clearly have to be a few of these institutions [like KhSA],” he says. “And we have to change about six generations of students. This is the passing on of a tradition: you need a school with various generations who have had discussions, friendship, sex—everything in one place.”

“No future, no future for you,” Drozdov cites the Sex Pistols song to explain the mood of his generation. He’s wearing all black; everything around him is white. Behind him are question marks next to the words “miracle” and “norm.” Alongside the former Bohoslovska building is a roof with a quote from a Conceptualist: “Not everyone will be taken into the future.” In its own way, Kharkiv’s spontaneous dialectic answers the question of how to live together.

Translated by Ali Kinsella.

[This publication was created with support of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Norwegian government.]

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More