A Tailor in a Cassock

On the wall of a perfectly white school classroom, the shadows of a man and two candlesticks rise above a thick, red-bound book. The candlesticks celebrate the liturgy in one way, while the young man in a snow-white shirt does it differently.

Father Ivan Horodytskyi is the priest of the Ladantsi village in the Lviv region, with the population of 304 people. Before joining the parish, he served in the Cathedral of Saint Volodymyr the Great in Paris but then decided to return to Ukraine. The father is 29. He has lived in Ladantsi for only three years. However, under his leadership, the local community has learned how to build things they have never built before: an interactive class, a youth center, and most importantly, a community where people could truly support each other.

Catechism

“You have to find a secluded place in the house. You need to be alone and remember what you have done so far, whether you have offended anyone with your words or actions.”

The dissatisfied rustle is heard in the room.

“Father, my mother will not allow me to do that.”

“Why not, Nazarko?”

“Because on Saturdays, there is no place in the house where one could seclude oneself.”

This is a class on catechesis in Ladantsi, where the subtleties of the Christian faith are explained. In the Western Ukraine, such classes are commonly held for children. Before the First Communion, which is usually received by the end of the first school year, the youngest parishioners are introduced to the basics of faith as well as the meaning of confession and prayer.

The man in a neat white shirt and pointy red shoes looks like a young couturier. Only his presentation of “five conditions of good confession” and a white altar behind him betray his priesthood.

“In the morning, Solomia or Myrosia tell you: ‘Nazarko, wake up! We have to go dig up some potatoes.’ What do you need to say first?”

“Leave me alone? I want to sleep?” The sincerity of a seven-year-old disarms the young priest. He smiles and asks:

“And after the confession?”

There is a short moment of silence. Then we hear one of the student’s doomed mutter:

“I guess, ‘Okay, I’m getting up now.’”

Against the approving children’s cries, the priest wisely closes the painful subject of potatoes.

He often smiles and frequently gestures. Yet he has to call it a day: it is a Saturday outside, and the kids have long exhausted their weekly reserve of patience and piety.

The doors close behind the last of the children, and we sit down to chat with the father.

“Just make sure to remove my red eyes in the pictures, please. I’ve had a hard week.”

Ladantsi

Ladantsi is a village on the outskirts of the Peremyshliany region. The village already has Internet but still no gas. At first, the father’s relatives were worried about the young priest who had fallen off the radar. Sometimes, it is difficult to get anyone even on the phone here. They often have no power, and to get to the other villages, one would have to walk across the fields, and only in good weather.

The hill and the path leading up to the doors of the priest’s house require patience and comfortable shoes. The father jokes that no driver has yet managed to get out of there without regrets or complaints. A seemingly safe hill is openly at war with any kinds of vehicles.

Many things in this house are Father Ivan’s “furniture children.”

The black coffee table emerged out of the two obsolete wooden icon settings, a mirror fragment, and the four legs of an ancient chair. Six wine glasses hang from a converted church beam. The improvised “wardrobes” were born of a few sticks and a Soviet curtain rod. The cute baskets underneath are actually the fabric-lined plastic fruit boxes from a local store.

“When you live in a village, you are like the king of junk. To me, everything is reusable, and all is recycled,” the priest explains proudly.

The parish house is being renovated: the roof, which they have only recently started patching up, still shamelessly lets in the sunlight, the occasional wind, and whatever else falls from the sky.

“When I arrived, the house was in a terrible state. The peculiarity of the Ladantsi parish is that anyone who has ever served here ended up leaving in a hurry. Some stayed for two years, others stayed less, while a few have been reassigned.”

In the Greek Catholic Church, priests practice obedience: they are expected to serve at the parishes assigned to them by the bishop and the church leadership. The bishop tends to listen to his priests, who would not be taken from their parishes without a good reason. Nor would the priests be left where they do not feel comfortable.

Three years ago, after the first repairs, the priest arranged for a snack buffet for everyone who had worked on the house.

“At first, nobody ate or drank anything; the French wine and cheeses just stood untouched. But after a few glasses and some snacks, the guests’ skin began to flush. They started talking about the things that bothered them. You see, there were scandals in the church before me because the priest was too harsh when he tried to change things. He called people names, and people called him names. It was a TV-like war drama going on here; I, too, was afraid that I would be expelled,” the priest explains.

Slim Fit

Since his childhood, Father Ivan has had a passion for handcrafting. His family was not well off, but kids need toys to play regardless of parental wealth, so he made koloboks out of old featherbeds. As Ivan’s sister Mariana recalls, in high school, her brother made for her and her mother exquisite beaded jewelry, as good as the accessories made by professional craftswomen. He wanted to apply to the Academy of Arts but eventually chose something else—the Seminary partnered with the Ukrainian Catholic University. The boy felt somewhat repulsed by the leisure of the art students—alcohol and cigarettes. But for the most part, it was his urge to serve the church that prevailed.

As a child, Ivan studied the priest in his native village. The priest had lost his entire family. His wife and children had died, but he served humbly. Horodytskyi believes that it was then that he thought of the unmarried priesthood for the first time. His parents rather quickly came to terms with his decision, but some of his relatives and neighbors acquiesced on the matter only after a few harsh exchanges with him.

“Once, near a store, they surrounded me and said: ‘Teach us how to live properly.’ I said simply: ‘Look at your own families. None of them was a model for me, for all you have in your families is discord, crying, and gnashing of teeth. What is there else to say when you are not even trying to be the role models for your own children?’”

In the seminary, Brother Ivan discovered a gift for sewing. He asked to be an apprentice for a seamstress who sewed for the theological academy. The boy quickly learned how to recreate chasubles (ceremonial clothing of priests), embroidered church tablecloths, robes, and hats. His fellow seminarians quickly realized that their peer’s sewing skills were their chance to modernize their own clothes. That was the time when the so-called “slim fit” became a trend, so Brother Ivan sewed fitted cassocks, pants, and shirts that emphasized one’s physique. He was even sent orders for church clothing from Europe. Bishop Taras Senkiv, the Bishop of Stryi, offered the boy a separate sewing workshop in the town. However, Brother Ivan declined the offer.

At some point, he even considered leaving the seminary, fearing he was not “worthy to be a vinedresser of the Garden of Christ.” Having travelled through the parishes of Ukraine, Horodytskyi witnessed excessive materialism, alcoholism, and other acts unacceptable within the priesthood that some priests allowed themselves.

“It is very easy to take Ukrainians out of the church, but it is very difficult to bring them back in. In Europe, no earthquake within the church would be a reason for a good Christian to leave it. Our people, however, would run away. The churches abroad try to rehabilitate and help people with vices. Here, though, you are a step away from getting stoned for a mistake,” the father shrugs wearily.

Go and See the World

Having finished his studies, Brother Ivan was ordained to be a deacon of the Stryi Eparchy of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC). After the ordination, however, he stayed in Ukraine for only a month: Bishop Borys Gudziak had invited Ivan to serve in the Cathedral of Saint Volodymyr the Great in Paris, where they experienced shortage of clergy. Horodytskyi agreed.

“When I came to Paris, I was kindly but clearly told that I would not become a couturier there and that I would not have a sewing workshop. I would go home, take my sewing machine out, and sew things in secret so as not to violate the instructions. In the Stryi parish, I was never prohibited from doing what I loved. So, Paris give up on my sewing,” the priest says sadly.

The father stayed in the church on rue Saint-Pierre for exactly one year and eight months.

“Ivan was just a vicar over there, with hardly any opportunities to communicate with people. Yet there is plenty of work to do in a village. Paris has become an opportunity to ‘go and see the world,’ and then come back and try to recreate at home all the good one has learned,” the priest’s sister Mariana explains to us.

When he decided to return, Horodytskyi surprised everyone who knew him. None could understand how one would voluntarily leave Paris.

“Through fields and swamps, Bishop Taras took me to a village. On the way there, he told me that the villagers had quarreled with their priest. When the Bishop got out of the car to speak to the people, I naively believed that this was not my problem. After I got out of the car, the people looked at me as if I were a minor wonder. The Bishop then told them that he brought to the village a new priest, who could speak French and teach them how to sew. At that point, I understood that he was talking about me. Oh, I thought, this was my problem,” the father laughs.

Horodytskyi later realized that he had already been here before, when, seven years ago, he had come to collect donations for the seminary. His most vivid memory of Ladantsi was that of the terrible architectural design of the local church, where he now was about to begin his service.

From Mice to Men

Father Ivan brought his favorite sewing machine with him. He used it to connect with the parish—through the needlework and the desire for beauty shared with the Ladantsi women.

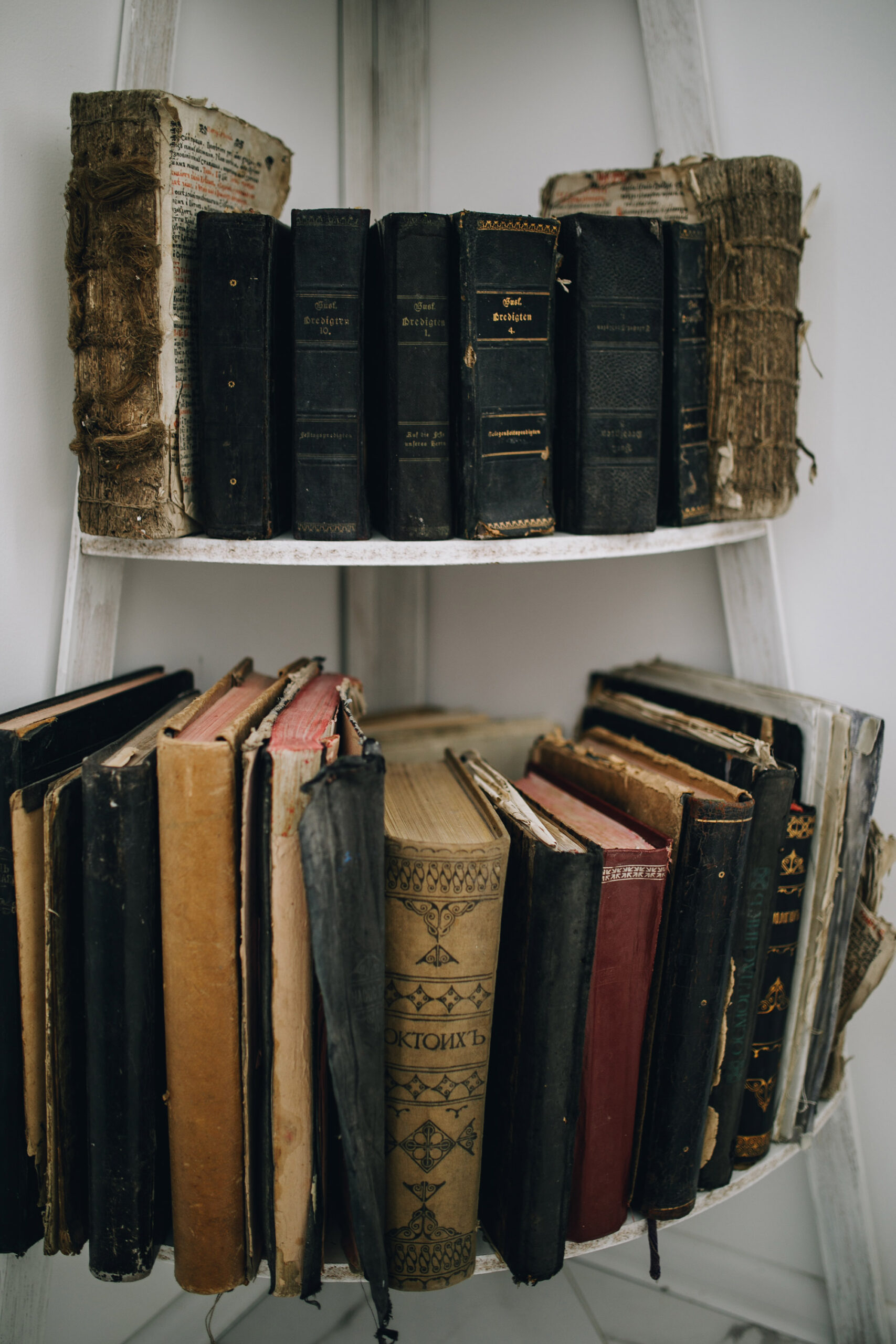

“The church chasubles were pretty bad. I could not serve in such rags; mice must have crawled all over them. Some even managed to have dined on them.”

For Father Ivan, perfectionism in the church matters is self-evident. The UGCC parish ordinance—the bill of parish priest’s rights and responsibilities—clearly requires from the priest to “ensure that the parish church is clean, tidy, and orderly, befitting the house of God.”

“So, during the fasting, I decided to sew the first chasuble for services. I told my parishioners: ‘See? We have saved together more than a thousand hryvnias.’ I knew that they were still uncomfortable with having a priest-tailor. Now, they have come to really appreciate my value for them,” jokes the father.

Father Ivan handed out to the local women the sketches of things that needed to be sewn for the church. He warned them that he would supervise their sewing so that it is done well, for God’s work must be perfect. To the accompaniment of music, singing together, female parishioners and their priest cut, embroidered, and tried to work out their roles in this new cooperative.

Soon the congregation began to gather in the parish house twice a week. The children would come to the catechism and the women would come to keep an eye on the children and incidentally probe a strange priest who had come to them. After all, the priests before would never invite any locals to their homes.

“In a family atmosphere, there is no division between the priest and the people. It really irritates me when a priest is unable to engage in a dialogue with his parish! Why would the parish need such a priest then?” Father Ivan emphatically asks.

Accents

His cultural offensive made much headway during Lent—because of the radically different views of the priest and his parishioners on the liturgical singing.

“When I came to the church, they sang such strange things that I felt sick. In church services, it is important to properly place accents to avoid embarrassing, comical mistakes. For a long time, we could hear: ‘Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit, now and ever, and сunto the ages of ages. Amen,’” says the father. “This ‘cunto’ was the final straw. I started closely watching every wrong letter and accent.”

Little by little, the priest began his career as a local conductor. Thirteen women who wanted to sing gathered for rehearsals in the parish house. At first, the goals were exclusively spiritual: the young priest was worried about the liturgy. Neither he nor the Ladantsi women have had any musical education. But the priest knew by heart the entire Easter morning service and was enthusiastic about passing this knowledge onto his parishioners.

The women studied for 5–6 hours a day. Each one went through an audition, and the father taught each one voice. The rehearsals were often visited by the controlling husbands, who at first did not quite understand what their wives had been doing this long with a young and unmarried priest.

It became clear during the Easter holidays when the Ladantsi choir first sang the morning service in the tradition of the Byzantine chanting—a cappella Octoechos (singing church texts in eight different voices without musical accompaniment). The father posted the video on the parish’s Facebook page and received many positive comments from his acquaintances in France, Poland, the Netherlands, and Germany.

“When I was asked, ‘So, who was serving when you were conducting the choir?’, I told them I was. Administered before the altar, and then turned around and waved at them,” Father Ivan recalls. “As soon as I arrived in Ladantsi, I almost immediately created a Facebook page for the parish. I wanted to show those in Paris, who were full of themselves and flew too high, telling me, ‘You’ll never get anything done in a Ukrainian village.’ I wanted to show them what could in fact be done.”

Christoforoses

After their triumph on social networks, the Ladantsi folks were invited to the choir festival in Morshyn. They had a repertoire, a conductor, and a lot of inspiration—only the name was missing.

“We have to carry God in us and live by the way of God, at least to a certain degree. And it shouldn’t be just like ‘see you at Easter’ and that’s all,” Father Ivan says with a slight irritation. “‘Fero’ is Greek for ‘bear,’ and ‘Christoforos’ means ‘Christ-bearer.’ This is how we came up with the name. After all, people have to call us somehow.”

The performance by the Ladantsi women, who had surprised everyone with their Christian spiritual hymns with Arabic and Byzantine motifs, caused a furore. Father Ivan’s friends abroad invited Christoforos to tour. Even the jealous husbands of the Ladantsi women conceded and quietly let their wives go—to serve the village and the arts.

In the three years, Christoforos has toured several times in Poland and Slovakia. People helped everywhere. In one of the Polish parishes, Father Ivan mentioned in a conversation that the community had been collecting money for the church’s floor insulation. Five minutes later, the local priest went up to the pulpit and announced that the donations from that day would go to insulate the church in Ladantsi.

“In total, we brought 46,000 hryvnias from the tour. Someone asked in the village: ‘What is that choir doing there?’ I said that this was the way for the Ladantsi women to earn money—not for themselves, though, but for the village,” proudly says Father Ivan. “We do not tour for money, though. For me, it’s essential that the people get to leave the village and see the world, and that afterwards, they get to come back here with bigger dreams and share them with others. It’s essential that they come to want to be independent and self-sustainable.”

Greek Catholic parishes operate in a similar way as non-profit organizations: their budget is based on voluntary donations from the church goers. Any financial decisions and the priest’s potential salary depend on how parishioners want to finance their own church. Most churches do not have any price lists for sacraments of baptism, weddings, or funeral services. Specification of any particular fee by the priest is unethical and unacceptable.

In the past, the Ladantsi church community did not raise funds for anything but the actual church needs. Therefore, the father has taught the parish to competently manage any funds they collected while touring or received from their benefactors. Now, they have several cash collecting registers in Ladantsi, each assigned to a responsible person—for garbage collection and sorting, for the choir, for the church, for international travel, or for cleaning of the Verkhovyna River, where they plan to build a village park. One parishioner is responsible for the Friends of Ladantsi Charitable Foundation, which has been set up to facilitate international remittances, because much of the help comes from Father Ivan’s friends in Paris. Recently they have taken care of the street lighting problem in the village. Thus one of the cash registers has solemnly fulfilled its mission and is now closed.

“The choir became the backbone of the parish’s functioning. If I need something, I can get it through the choristers. If I ask them to do something in the middle of the night, they will get up and do it. And not because I want to, but because it is necessary for our big family,” the father explains.

Sins

“There was a dairy in Ladantsi known throughout the region. They made wonderful cheeses and butter, even sent them to Holland. When the USSR came, everything fell apart,” Father Ivan raises his voice, trying to talk down the jingles that accompany the ongoing reconstruction of a large dim-grey building

The Soviet authorities turned the dairy into a “people’s house,” which eventually fell into decay. After the collapse of the USSR, Ladantsi was given a two-story building, steeped in the Soviets, in the center of the village. The locals decided to give it a new life—to create the Verkhovyna youth center named after the local river.

Before, it was the local shop where the youth used to hang out together. The leisure time itself was limited to collective drinking of alcohol. The father and the community planned to build a modern-style center: minimalism, a neat bar counter, a corner lounge set for parents with kids. They have been planning to lay warm floors and arrange for a medical facility. And the last touch would be a beautiful terrace on the second floor. Paid by the foreign benefactors who, after the European success of the choir, help the village through the Friends of Ladantsi Charitable Foundation, the locals have already built a new roof for the center. However, the construction of the youth center has stalled because of the growing organized youth drinking.

“I caught them once binging inside the half-finished center,” the father emphasizes. “One day, I stopped by at midnight, still wearing my cassock, and took a picture. I told them: ‘Each one of your families has someone addicted to alcohol. You complain about it, but you don’t do anything better.’”

So, the parish is planning to arrange for an internal control system for the youth center. They want to build two separate entrances: one for the young and the other, for the older villagers, so that they could come in without warning and break up any unwanted gatherings that may attract minors.

Father Ivan defines the fight against alcoholism and “judging not thy neighbor” to be the two pillars of his pastoral activity in Ladantsi. There are fewer young people in the Christian service of God than in the service of Bacchus.

“Before my arrival, there were places selling moonshine in the village. However, they later self-liquidated. I had to make a lot of noise, even though a priest’s job is to pray. We often organize a Cross procession for all alcohol and drug addicts,” shares the parish priest.

Condemnation holds the second place in the father’s “sins chart.”

“I often hear people complain about the government or their neighbors. People rush to condemn because they want to run away from their own problems. They tell others what to do, because they don’t know how to help themselves.”

People

More than a hundred steep wooden steps lead to the St. George’s Church, making it difficult to reach the church on the hill in bad weather or even during a mild winter. One of the school buildings in the center of the village was empty, and the priest suggested that it be used as a common area for villagers, where adults and children would come to study, and the elderly and the sick, to pray.

Father Ivan planned to create an interactive classroom there. “On Facebook, I found out about the Lviv Educational Foundation, which helped social initiatives of church communities, and I really wanted to get that grant.”

“In the application, we immediately stated that we would arrange an interactive classroom with a projector and speakers, which will serve both the church and the people. I won’t pretend that the whole village comes here and we are all just a happy and joyful family, like Jehovah’s Witnesses. Ten people would come during the week, 15–20 would come to watch a movie. Last time, we had 36 people at a night prayer vigil before the holiday.”

All the repairs in the classroom were completed by the Ladantsi residents. The father paid them from the foundation funds; however, the villagers took only half of the fee. They gave up the rest to cover the other needs of the parish. A weekly Bible class and choir rehearsals are held in the classroom, and the children’s catechism is held twice a week. The Ladantsi school, meanwhile, uses the classroom as an assembly hall.

“I am somewhat frugal by nature. I knew that there were a lot of old broken chairs in my seminary. One such chair costs at least 500 hryvnias, and we repaired those for our class for free.”

Later, the father went to visit his friends in Germany. On his way, he thought about what a Catholic priest with a cross on his chest would say to a Calvinist parish.

“The local pastor there told me: ‘Ivan, we know everything about your village. Here is your money. You don’t need to give us any reports; do whatever you need to do.’ Everything collected from the Christmas fairs and caroling was given to us. We received another 108,000 hryvnias for the class,” the father rejoices.

That pastor was supposed to visit us, but he could not because of the coronavirus. He said he envied me in a good way because he had the facilities, the money, everything—all but the people. “Be sure not to waste those chairs,” he told me. “With no people, no one needs the chairs.”

[This story was created with support of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Norwegian government.]

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More