Manufacturing in Two Shifts

Nagender Parashar made the journey from Delhi to Kyiv when he was 17—right after Ukraine gained independence. He studied computer programming at the National Aviation University, but it somehow never worked out. Perhaps, it was just not the best time. To get a foothold in a country that was still foreign to him back then, Nagender, a native Indian, took up whatever work he could find. In 2008, he was offered to “lug stuff”—to import prosthetic components into Ukraine. Without prior experience in this business, he started to organize deliveries from China. But he was not satisfied with the quality of the goods. Nagender was used to doing everything properly, so he apologized to his clients and promised to find better suppliers. He didn’t have any success, though.

“Then I said to myself: I can no longer live like that,” he recalls.

So he decided to make components by himself.

To keep your footing

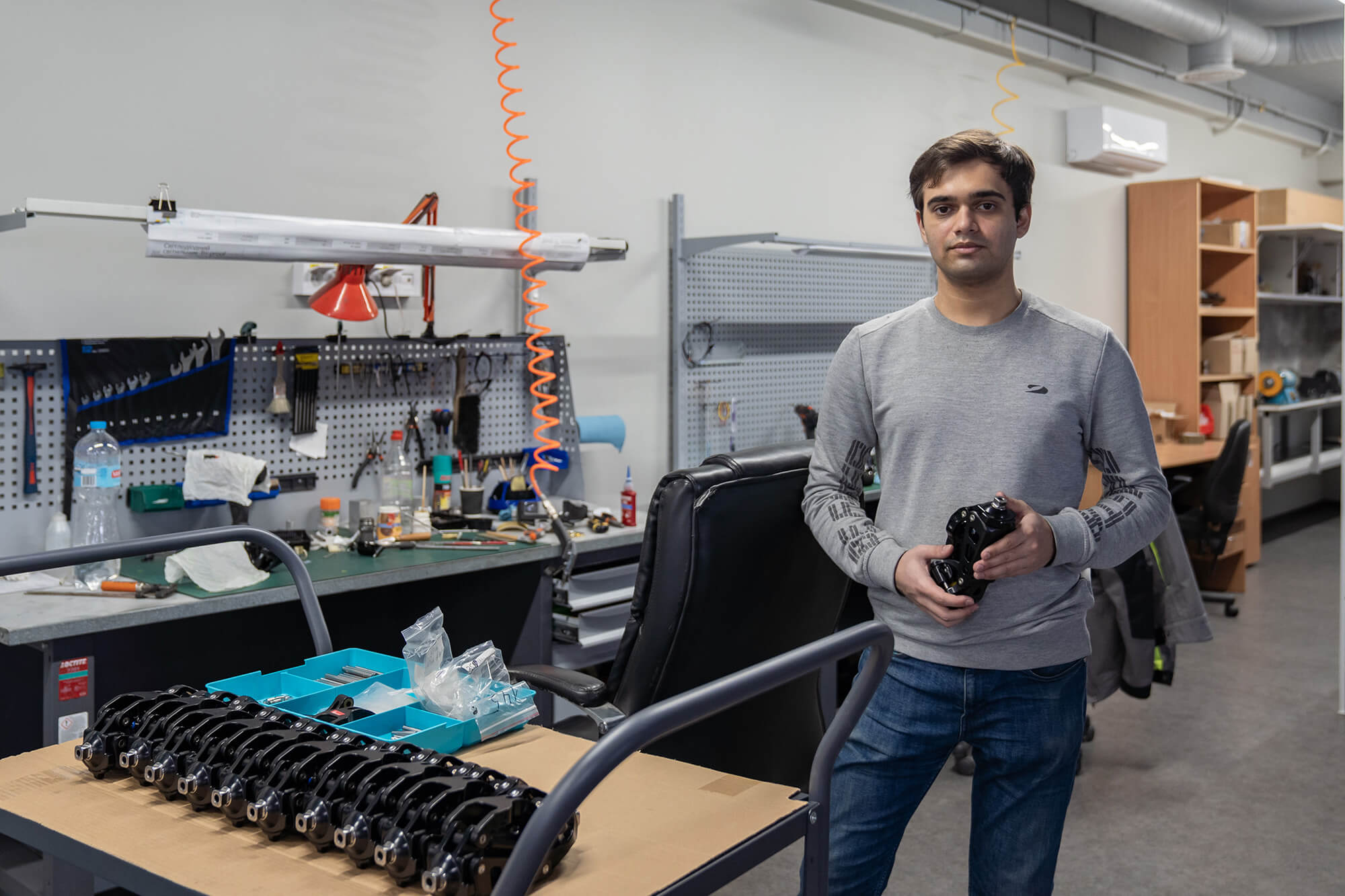

“I stumbled into product engineering by chance, all because of issues with Chinese product quality. I identified the issues their products had, searched for solutions, and suggested them to the Chinese manufacturers. Initially, I lacked the knowledge to create technical drawings, but I gradually learned the process. I procured components from all over the world and then took them apart and analyzed how they were made. Then I attempted to make my own parts, starting with mechanical and then hydraulic components,” says Nagender, whose company now, many years later, bears his name. He runs his business together with his son, who’s studying computer engineering at the very same National Aviation University.

In January 2014, Nagender had the most basic Chinese machines shipped to Kyiv. Today, the centers for prosthetics, orthotics, and rehabilitation “Bez obmezhen” (“No Limits”), which he established, operate in nine Ukrainian cities. And Parashar Industries, the company he set up in 2016, remains Ukraine’s only producer of prosthetic components to this day.

In August 2023, The Wall Street Journal published a report stating that around 50 thousand Ukrainians lost their limbs in the first seventeen months of the full-scale invasion, a figure it attributed to an analysis by the German company Ottobock, the world’s largest prosthetic producer, and its healthcare partners.

However, it’s important to note that there’s a significant interval between amputation and receiving prosthetics, so this figure is almost certainly an underestimate..

Since August, another seven months have passed. Combat actions and Russia’s shelling of peaceful towns and villages have not relented. . Today, we live in a country that has no right to neglect inclusivity.

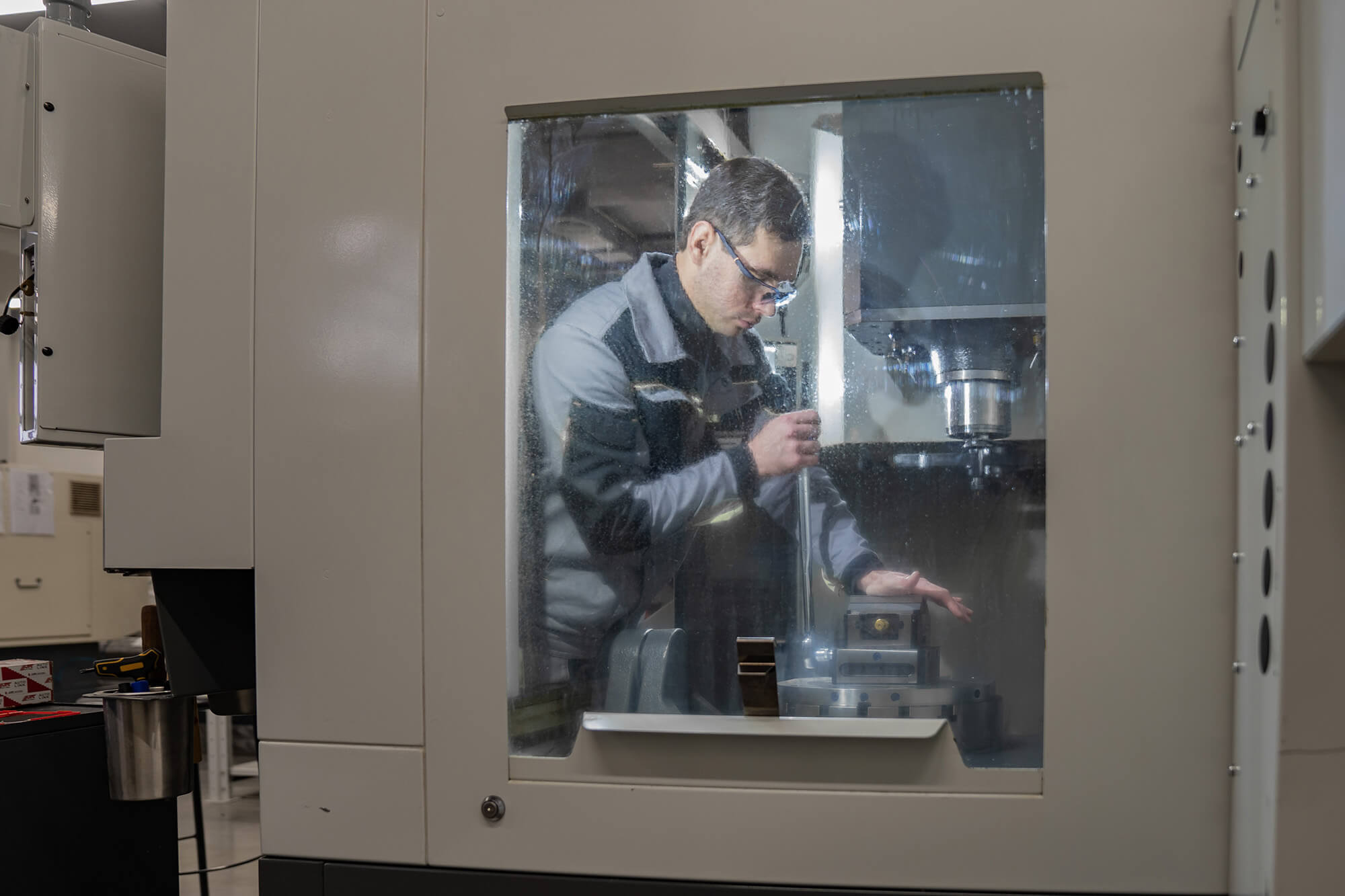

Parashar Industries, a small family business with 26 employees tucked in the middle of a suburb of Kyiv , now operates in two shifts. On the ground floor, machines whirr—these ones are made in the US, and programs for them are written by students who learn by doing. One floor up, the components are polished, tested for strength, and packaged. A bit further down the hallway, in the smallest office with a drawing board, Nagender and three other product engineers work on improving existing products. Currently, they are focused on creating feet for sports prosthetics, specifically for CrossFit workouts.

Most of us hardly ever think about how many actions our feet, calves, and knees perform every single day as we walk, shifting weight from heel to toe—as we speed up, stop abruptly, go down the stairs, step over curbs, jump over potholed sidewalks, sit down, work out, or lift weights in the gym. From dawn to dusk, our feet bear the weight of our bodies, help us maintain balance, prevent falls, and remain fast, nimble and agile.

Nagender and his team think about this constantly. Their daily task is to ensure that metal and plastic recreate the marvel of human nature, with its muscles, tissues, blood circulation, and nervous system, as faithfully as possible.

Today, Nagender Parashar keeps his feet firmly on the ground as it trembles and shudders like never before. He helps others keep their footing, too.

Metal’s way

After undergoing amputation and a lengthy rehabilitation process and getting a disability category assigned, individuals must apply to the Administrative Services Center or the social security agency for a prosthesis. The agency will provide them with a referral, and the applicant is then free to choose a prosthesis provider.

According to Oksana Zholnovych, Ukraine’s minister of social policy, around 80 prosthetic providers currently operate in Ukraine. Collectively, they manufacture an average of over two thousand lower limb prosthetics and around two hundred upper limb prosthetics every month.

These companies, both state-run and private, commission components from Parashar Industries, which boasts three dozen employees and uses several American machines.

“A prosthesis is supposed to serve for at least several years,” Viktoria Subbotina, deputy director at Parashar Industries, says. “It should not wear down. If anything goes out of order, a person contacts the prosthetics center, and the center contacts us. We fix the issue on-site in a matter of days. This is our biggest advantage. We would like to manufacture more knee joints so we could do timely maintenance of prosthetics; otherwise, they would just lie there broken because their owner could not actually make it to the prosthetics center. I’ve been working in this industry for a decade, and I know how horrible it is when someone has a negative experience and feels discouraged to push forward.”

To prevent prosthetics users from having negative experiences, the company consistently improves its manufacturing process, with a main focus on hydraulic knee joints. These joints are manufactured in only a few countries, primarily in Japan and the UK. The process is labor-intensive, as a moving knee consists of 39 components, and the company covers the full cycle.

“Unfortunately, there’s an exponential increase in demand,” Viktoria says. “We are very busy. All prosthetic providers, all rehabilitation centers are very busy these days. Manufacture is followed by warranty and post-warranty maintenance. This is provided by prosthetic and orthopedic companies working under the government program and Decree No. 321 ‘On providing auxiliary means of rehabilitation for people with disabilities.’ This is how most people get their prosthetics.”

Then she adds with a sigh that she can no longer bear watching volunteers collect plastic bottle caps that should supposedly be used for making prosthetics. This myth has been circulating for years, even though this kind of plastic is not suitable for production.

Overall, when it comes to lower limb prosthetics, there are four levels, known as “K-levels” based on the person’s functional abilities. K1 level is when the person is bedridden; K2 level is when they are active and work out. When designing prosthetics, engineers take into account the person’s weight, comorbidities, and lifestyle. The prosthetics provider and orthopedic traumatologists are both responsible for testing. Viktoria says that after an amputation, wounded soldiers often want to return to service or active civilian life as quickly as possible. Currently, Parashar Industries manufactures spare parts for K1-K-3 level prosthetics designed for maximum patient weight between 125 and 136 kg. However, the company’s engineers have already started testing models of artificial feet and knee joints for sports prosthetics.

“We’ve set up an experimental production workshop. One of the niches is manufacturing prosthetic feet. We’ve already created an experimental sample of feet for CrossFit. All products are tested on a special machine, where five to 150 kg of weight put pressure on the prosthesis—three million times on the toes, and another three million on the heel,” Viktoria explains.

The experimental production floor will be housed one floor up. Meanwhile, Viktoria gestures toward two shiny milling machines in the middle of a small production room.

“These two beauties are our newest additions,” she says proudly.

But the biggest challenge is not sourcing equipment but finding skilled personnel. To address this, the company signed a dual education memorandum with the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute (KPI). Students working at the company are trained as manufacturing engineers: They configure programs for turning spare parts designed by Nagender and their fellow KPI students in the office above the production floor. Recently, the company donated machines they no longer used to the university so it could train students.

“We can’t find specialists on the job market, so we nurture them ourselves,” Viktoria explains. “Many people left the country, and many others are fighting in the war.”

She has managed to pull out two experts from the maelstrom of the war.

People and their hands

Vadym Voitovskyi, 55, scrapes the components, his hands silver with aluminum. He’s completely absorbed, working beneath cold, electric lighting.

He commutes from Tarasivka, a village outside Kyiv where he now lives, and always arrives half an hour early to have enough time to lay out his tools without hurry and organize his workspace—just as he did for the past twenty-five years at the Ilyich Iron and Steel Works of Mariupol, which no longer exists. Vadym began his last shift on February 26, 2022, as the whole city was shuddering from explosions.

Soon, the power went out, just like the internet and cell signal, and people and buildings started to disappear. The Ilyich Iron and Steel Works disappeared, too.

By sheer luck, Vadym and his family managed to escape the city in mid-March. Four months ago, Viktoria, who was scouting for talent, met him on a local Telegram channel. Vadym loves his craft and believes it will soon be even in higher demand than it is today.

“Every employee contributes to the quality of the end product in one way or another. Your feet are in good hands,” he says, laughing, as he observes a technician at work.

Through the same channel, Viktoria met and hired another resident of Mariupol. Kateryna used to work at the social security department of the Mariupol City Council. Now she’s transitioning to HR.

“These people have great potential and can be valuable in any part of our country. They miss their homes very much, but they’ve found a new family here. We keep everyone busy,” Viktoria says with a smile.

Nagender is confident that his company could easily tap into the export market. However, at present, they must channel all their efforts into meeting domestic demand.

“Unfortunately, Ukraine is evolving into the world’s prosthetics hub, drawing experts together. It’s becoming a permanent daily routine,” he says.

Nagender is striving for balance. His spare parts must be more affordable than those from American, British, or French manufacturers because Ukraine lacks a culture of insurance to cover expensive electronic knee prosthetics. For this reason, he focuses on manufacturing hydraulic knee joints. They also must be safer and more reliable than their European counterparts, considering that prosthetics made in Ukraine will navigate streets not adapted to people with amputations. Nagender also conducts research with a limited budget and external financing, all while trying to bridge gaps with his own finances. Several state-run prosthetics factories that Parashar Industries collaborated with went bankrupt, defaulting on their debts to his company.

Often, instead of engaging in “creative work”—tinkering with knee joints and preparing yet another set of drawings—Nagender finds himself immersed in a slew of bureaucratic procedures, writing dozens of emails, and learning to deal with the government that keeps changing the rules of the game, barely informing anyone about the changes.

“Can you see how the weight shifts? It’s a load transfer point,” he explains, slowly rolling a prosthetic foot from its toes to the heel, demonstrating careful steps in front of the laptop camera—he’d taken his samples to yet another international meeting.

Maintaining balance is crucial when walking—especially on the ground that trembles mercilessly.

Life after the injury

Oleksandr Shvachko, 37, has been using the mechanisms made by Nagender’s company as part of his new prosthetic limb for around eighteen months. A two-time military volunteer, in 2015, he served in the 79th Airborne Brigade (now the 79th Air Assault Brigade). He later returned to civilian life, finding a job in sales. On the first day of the full-scale invasion, he brought his fellow soldiers together, and they all joined the 95th Air Assault Brigade, which helped retake control over the Kyiv region.

“In Makariv, we assembled a group to venture into the gray zone,” Oleksandr says. “Our task was to establish a foothold and secure fire superiority over one of the roads in the industrial zone. On March 12, we destroyed a Russian sabotage-reconnaissance group and stopped their assault. The next day, we captured a hostage, and Russians renewed assault on our positions. A tank rolled in from one flank, and another tank and an infantry fighting vehicle with infantry backup came from the other. They broke through the fence and fired at us at close range. One of our grenade launcher operators was injured, and another one was killed.

“So, I picked up the grenade launcher and fired. I didn’t manage to take another shot, though, since I was wounded by a fragment of a tank projectile.”

Eventually, control over the gray zones of the Kyiv region was retaken at the cost of Oleksandr’s health—and the health and lives of his comrades—and Russian tanks no longer loomed on the crushed fences. Meanwhile, Oleksandr underwent complex treatment and rehabilitation in a range of hospitals, both civilian and military. The stump of an amputated tibia wouldn’t heal—it hurt and secreted discharge. A month later, a re-amputation had to be performed, with another segment of his limb being cut. As soon as his leg started to heal, Oleksandr and his comrades began going out to an athletic field. He couldn’t wait until he recovered. Oleksandr chose one of the Bez Obmezhen centers to make a prosthesis for him. He started learning how to walk on a practice prosthesis and then ordered an everyday prosthetic limb. It was only by that time that he’d been discharged from the Armed Forces and could return to his previous job as a sales manager.

“In February 2023, I got a call. It was from the president of the Strongman Federation of Ukraine, an association of strength sports for veterans,” Oleksandr recalls. “I started training with them and participated in all-Ukrainian competitions, bringing my comrades on board. We toured many cities and, as a result, assembled a team of eight people. All of us have limb amputations, and one has double amputation. As part of the Strong Ukraine project, we participated in the Arnold Classic Europe Festival in Madrid.”

The team pulled four trucks weighing a total of 35 tons for a distance of 20 meters in just 30.69 seconds, establishing a new world record for adaptive strongman competitions.

A week after returning from the festival, Oleksandr traveled to Washington, D.C., for the Marine Corps Marathon. There, he ran his first ten kilometers—this time on a sports prosthesis. He did so because he couldn’t say no to a fellow soldier with more serious injuries.

Oleksandr doesn’t have his own sports prosthesis yet. According to Ukrainian law, he becomes eligible to receive one funded by the government only a year after participating in his first competition and at the request of a governmental agency. However, he’s already bracing for this convoluted process.

In Ukraine, he continues what he’s been doing. Recognized as an ambassador of Strong Ukraine, he doesn’t miss a single competition. He also visits hospitals and rehabilitation centers to engage other veterans in sports.

“Sports is truly one of the most effective methods of reintegrating veterans into society,” Oleksandr says, recalling his personal experience.

More than two years ago, a fragment of a Russian tank projectile threatened to turn his life into a gray zone between war and civilian life. Returning from this zone is incredibly hard. Reclaiming color in his life required the efforts of many people: Oleksandr himself with his will to live, doctors and rehabilitation specialists, fellow soldiers and advocates of veteran sports, and the teams of the Bez Obmezhen center and Parashar Industries. What Russians are trying to destroy, people are trying to reclaim, acting together, step by step.

“The Power to Continue” is a collaborative project between the United Nations Development Programme in Ukraine and Reporters. Our goal is to share unique stories of veterans and civilians who have lost limbs in Russia’s war against Ukraine, and not only found the strength to survive the trauma but also became drivers behind social projects and bold business ideas. We also highlight the stories of people who have helped them along the way. While there are not many of them, these people inspire and speak openly about their experiences, and this might become a starting point for others.

The special project was initiated by Reporters with the assistance of UNDP in Ukraine and financial support from the European Union as part of the “EU4Recovery—Empowering Communities in Ukraine” project. The opinions, recommendations, assessments, and conclusions expressed in these materials do not necessarily reflect the official position of UNDP, the EU, or their partners.

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More