A handful of breadcrumbs

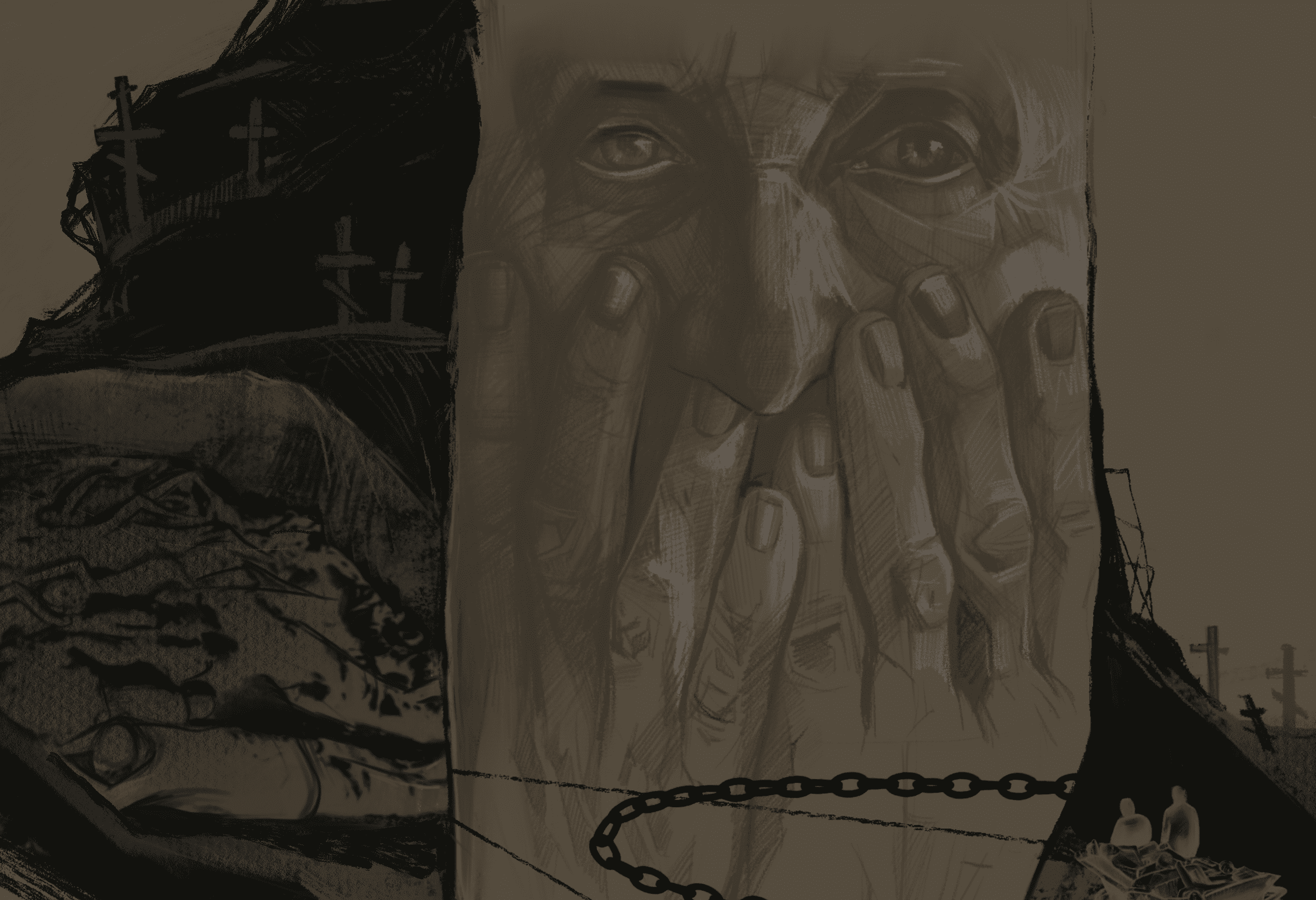

It was the early 1960s. In the village of Korobchyne, Kropyvnytskyi district in central Ukraine, two strangers came into local resident Sydir’s yard.

“Sydir Kozhukhar, son of Pavlo?” one asked him.

“Yes…” he replied.

The conversation was curt.

“Even if anything has happened, you better forget about it, got it?” the stranger added. “Any more babble, and you’ll die — since you failed to die back then.”

“Back then” referred to the time thirty years before, when half the village of Korobchyne starved to death, including close members of Sydir’s family.

In one of the most abundant grain regions of Ukraine, corpses lay in the streets until a cart collected them and took them to a cemetery, where they were thrown in a mass grave.

In 1932, Sydir was in his forties. He had a family of his own, his wife Mania and their two kids, an eight-year-old son Mytia and a four-year-old daughter Nastia. Their food was scarce. Villages were targeted by the leaders of the Soviet Union, whose policies, including collectivisation, resulted in a man-made famine which severely affected the farming areas of Ukraine. Therefore, Sydir carried his most valuable belongings to the nearest city, to barter them for something to eat. On his way back home, thieves stole his sack of food for his family. Not wishing to return empty-handed, Sydir stayed longer to earn this back. When he eventually returned, he found nothing but heartache.

“Cry loud, so they can hear you”

It is 2023. An 86-year-old Raisa is sitting in a room with Orthodox icons in God’s Corner, an altar embellished with artificial flowers. Hanging on the walls are discoloured photos of herself, her husband, and their three sons.

In the 195os, a 17 year-old Raisa married Sydir’s son Mytia, and entered the home as Sydir’s daughter-in-law. From day one, she would call him “father”, as she did not manage to be raised by her own dad.

She tells how Mania starved to death while Sydir was working in the city.

“They had a dozen chickens, so there were some eggs in the house,” says Raisa. “She fed those eggs to her children, one per kid every day, and never ate anything herself. ‘I’ll eat when Sydir returns,’ she used to say. And she starved to death.”

Raisa shares the story of the woman whom she never knew as her mother-in-law. Her voice is even, emotionless — however, the silence she falls into every now and again shows the story never gets less distressing, no matter how many times she retells it.

When entire families are dying off and death itself becomes a trivial matter, people become desensitised. When Mania died, her mother and sister came to their house, arranged her body, put her on a piece of sackcloth in the middle of the house — and left. By now, it’s academic why no one bothered to remove her or to at least inform the men who were piling up corpses.

The two kids were left in their home with their dead mother. It was summer. By the time the Kozhukhars’ neighbour finally realised that she hadn’t seen Mania for a while, and went to find out what was happening. At the threshold to the house, it was clear. A puddle of fluids issuing from the dead body had reached the doorstep.

Sydir’s cousin, the head of the local kolkhoz [collective farm], was unphased by the situation, and asked Mania’s mother “How come your son-in-law is hanging around somewhere, and I’m the one who’s supposed to take care of his family?”

However, he agreed to provide a coffin, and to give Mania a burial. The neighbour gathered all those close to her, and together they prepared Mania’s remains.

However, the corpse was falling apart, and pieces were slipping off its cloth bed. To keep the body together on the fabric, they used tongs for placing hot pots on a stove. They clipped the ends of the hessian and dropped the remains into a crude wooden box. Mania likely became the only person to be buried in a mass grave inside an actual coffin.

On that very day, the neighbour took Mytia and Nastia to an orphanage, which was full of other children, most of whom did not outlive their parents for very long.

She left the kids on the doorstep, and told them, “You should cry loud, so they can hear you.” The kids obliged dutifully and were taken care of until their father returned.

When Sydir came back, his house was looted, and his chickens were stolen.

Sharing the secret to a perfect loaf of bread

“Father was a good man. Not once did he hurt me in any way, and sometimes, when my Mytia and I fought, father always stood by me,” says Raisa. Talking about the man who taught her every life skill isn’t easy. “He was lying on a seat above the heating stove, hanging his head over the cooktop, and giving me instructions, like, ‘Add three bowls of flour… now add water… and mix until I tell you to stop. Now add the bread starter…’”

To make such a bread starter, one must boil hops in water, and then mix in flour until the dough thickens, add some homemade yeast, and put the bread onto the oven. Once the dough gets puffy, it is divided and formed into loaves.

After he reclaimed his children from the orphanage, Sydir had a relationship with another Maria, who had approached him. “Let’s move in together,” she said. “I’ll take care of your kids.” He agreed, as living without a mistress of the house was hard, and they all went to stay in her house.

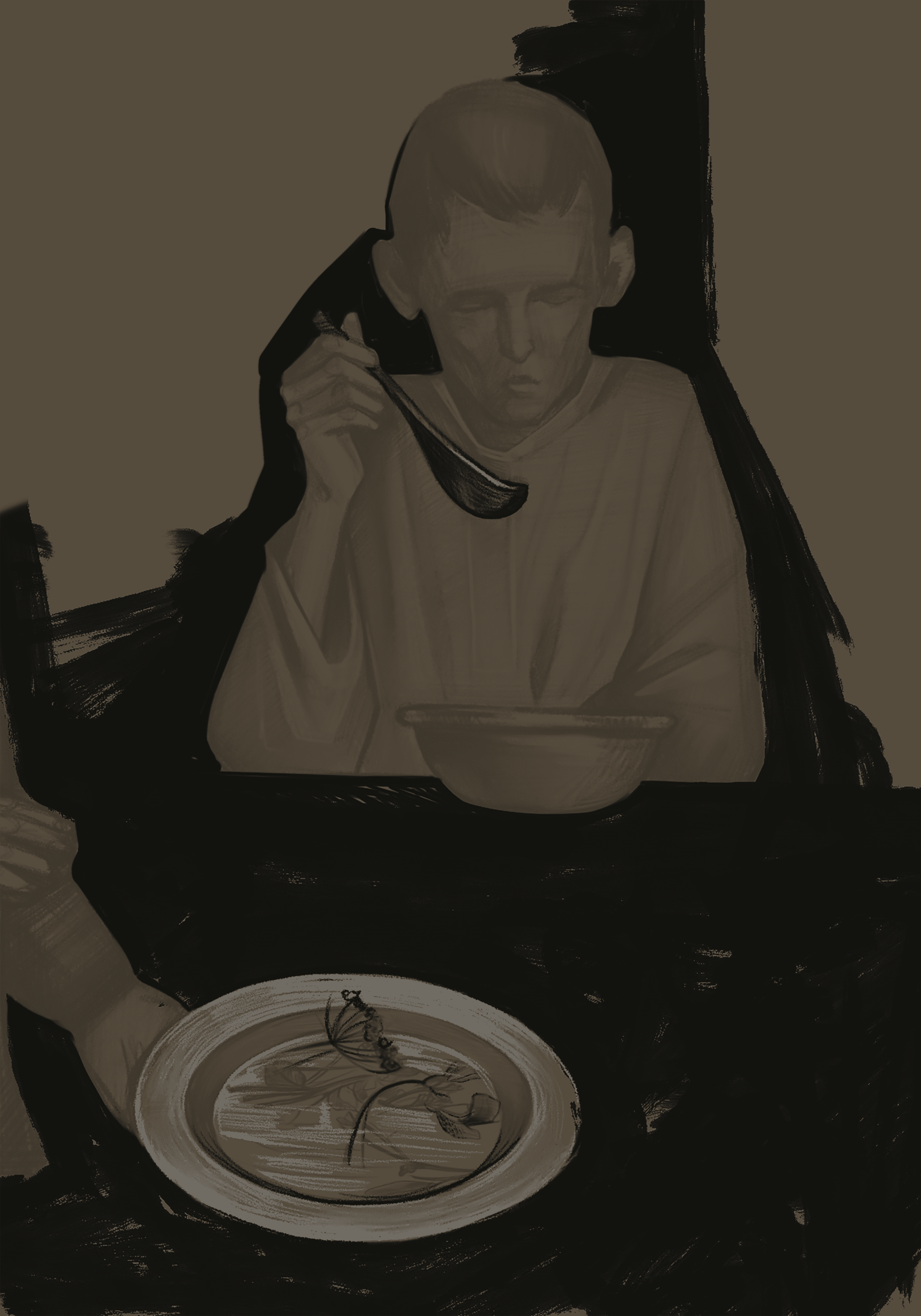

“She used to brew some soup,” says Raisa, “and sit the family around the table (back then, the entire family all ate from the same large bowl), and that woman got the thick of the soup for herself and father only, leaving the kids with just broth. ‘Eat, sweet children!’ she said. So father realised it wasn’t working out, took his kids, and they returned to their old house.

“There was nothing that Sydir couldn’t do. If he didn’t know how to do something, he taught himself. He was short, fair-haired and light-eyed. Many other women from the village asked him out, yet he always declined, ‘I gave it a try,’ he said. ‘It didn’t work, I’m done.’”

He never remarried. Besides, soon enough he had a lot of other things to worry about: the food he earned was gone, while the famine persisted. Nastia died next. As there was nobody to take her to the cemetery, Sydir buried her in their yard. His young son Mytia was bloated from hunger. His skin was paper-thin and breaking apart. Water from his body was dripping through these fissures, along with the boy’s life. He could do nothing but sit on a bench, and watch the liquid fall from his heels.

Sydir, exhausted, placed his barely alive son Mytia by the icons in God’s Corner, so the child wasn’t visible through any of the windows. There was a danger that some children were at risk of being taken, as there was talk in the village of children “disappearing”.

He told his son, “Sit still and don’t go anywhere. Should anyone call, don’t answer.” Mytia, however, was unable to go anywhere: the kid was so malnourished that he lost his eyesight.

“Sydir was walking down the road, and the cart collecting bodies was passing by. Seeing that he was barely alive, they picked him up and threw him on the pile for the cemetery. There, they dumped the dead and the dying, into a deep pit.”

The wagon took those who were close to the end, so it would save on a trip to pick them up when they had actually died.

Raisa lowers her gaze and for some time, she looks over her carved walking cane that she leans onto, her hands clutching the wood. It takes her a while to resume her story.

“When he was thrown into that pit, he was unconscious, out of fear or exhaustion. There he lay, until nightfall, when it got colder and the air got fresher, and then… there was some rain — or was that dew? — that brought him to his senses. He realised he had a kid locked in their home. What would become of his boy?”

“He was lucky that no one bothered to fill the hole with earth. However, Sydir couldn’t even try to get out, as his legs wouldn’t hold. He fumbled around and found a walking stick by one of the corpses. He used that cane to dig into the wall of the pit, and was able to climb out, but it was tough, as his hands weren’t listening to him.”

Sydir confided in Raisa’s eldest son that someone’s walking cane wasn’t the only thing that saved him in that pit. When lying inside, he thought he could smell bread. The man searched around and found stale bread in a dead man’s pocket. This morsel failed to save its previous owner’s life, but it was vital for Sydir.

So he got out and went home. He walked, crawled, lay to rest briefly, and then forced himself to walk again. The man reminded himself that his son was all alone. When Sydir finally opened the door of his house, Mytia was still alive. The boy was sleeping, nestled on the bench, in the same spot as before.

It’s unclear whether it was that dead man’s stale bread that put new heart into Sydir, or another spell of hunger that cleared up his fogged mind, but he remembered seeing a mound of earth in the ravine behind their home. This was a burrow, where something was living. If they had any chance of surviving at all, that was it. Sydir took a sack and went to that ravine, placed the fabric at the entrance to the burrow, and fixed the edge to the ground with rocks. He dug a hole nearby which fed into the burrow, and started a fire, so the tunnel would fill with smoke. Annoyed by the fumes, a badger ran out, and charged into the sack.

Weeds, saltbush, mallow flower and pieces of badger made a broth that Sydir nourished himself and his Mytia back to health. Eventually, the kid regained his eyesight.

Meanwhile, their old house began to collapse, so Sydir and his son spent some time at other people’s places until they had enough building materials to rebuild their own. Nastia’s remains, as those of many of her fellow villagers, stayed buried in her yard.

Half a century of silence

It was around 1959 or 1960 that the villagers were able to secretly pick up Voice of America. In one of those broadcasts, they heard a story of a man named Sydir who was almost buried alive during the famine.

This was a few years after Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin gave a speech in New York, revealing details of the 1932-33 genocide against Ukrainians. So the rest of the world was open to understanding what happened, and not to be fooled by Soviet propaganda.

Not only was Sydir’s story believed, it was retold on the radio in great detail, including the man’s full name, as well as the name of his village. It is assumed that the story came from someone from the village who managed to escape abroad. However, the exact source was never clear.

Shortly after, a car stopped by Sydir’s home, and two strangers threatened the old man into shutting up and forgetting all about it.

Did members of the village discuss what they went through? Even if they did, they were secretive about it. There was no time for grief, as their kolkhoz had work for them, which they were obliged to complete in full. Then came World War II, and after that, another famine.

Following that “visit”, Sydir forbade his family from raising the topic again. Whenever he was asked about that pit in the cemetery, he always replied that he had never been thrown into it. There was no pit. There was no near-death experience and a miraculous rescue. Instead, there were almost 45 years of silence. Sydir’s eldest grandson was the only one to whom he confided what he really had gone through. He ordered the lad not to share a word of it while the grandfather was alive.

“He always reproached us for wasting bread,” recalls Raisa. “He used to pick every crumb from the table, so nothing was wasted. That’s what I always do, too.”

The woman mimes the gesture of brushing scraps from the table into the flat of her hand, and emptying the contents into her mouth.

She kept her word. 45 years after Sydir’s death, she has pieced together his story, from the crumb-like recollections he told their family, which she now shares with others.

The woman who grew up with no father keeps vigil over the story of the man who lost his wife and daughter to the Holodomor. She cherishes this story, just as she cherishes the bread-baking skills she learned from her father-in-law.

*

The National Memory Book of Holodomor victims contains 880,000 names, including a list of 55 villagers from Korobchyne. Three of them are surnamed Kozhukhar, and two of those are Sydir’s immediate family.

“Kozhukhar, first name unknown, DOB unknown, died of hunger.

Kozhukhar, first name unknown, a minor, DOB unknown, died of hunger.

Kozhukhar, first name unknown, a minor, DOB unknown, died of hunger.”

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports130

More